|

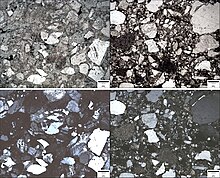

Greywacke  Greywacke or graywacke (German grauwacke, signifying a grey, earthy rock) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness (6–7 on Mohs scale), dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or sand-size lithic fragments set in a compact, clay-fine matrix. It is a texturally immature sedimentary rock generally found in Paleozoic strata. The larger grains can be sand- to gravel-sized, and matrix materials generally constitute more than 15% of the rock by volume. FormationThe origin of greywacke was unknown until turbidity currents and turbidites were understood, since, according to the normal laws of sedimentation, gravel, sand and mud should not be laid down together. Geologists now attribute its formation to submarine avalanches or strong turbidity currents. These actions churn sediment and cause mixed-sediment slurries, in which the resulting deposits may exhibit a variety of sedimentary features. Supporting the turbidity origin theory is the fact that deposits of greywacke are found on the edges of the continental shelves, at the bottoms of oceanic trenches, and at the bases of mountain formational areas. They also occur in association with black shales of deep-sea origin. As a rule, greywackes do not contain fossils, but organic remains may be common in the finer beds associated with them. Their component particles are usually not very rounded or polished, and the rocks have often been considerably indurated by recrystallization, such as the introduction of interstitial silica. In some districts, the greywackes are cleaved, but they show phenomena of this kind much less perfectly than the slates.[1] Although the group is so diverse that it is difficult to characterize mineralogically, it has a well-established place in petrographical classifications because these peculiar composite arenaceous deposits are very frequent among Silurian and Cambrian rocks, and are less common in Mesozoic or Cenozoic strata.[citation needed] Their essential features are their gritty character and their complex composition. By increasing metamorphism, greywackes frequently pass into mica-schists, chloritic schists and sedimentary gneisses.[1] VarietiesThe term "greywacke" can be confusing, since it can refer to either the immature (rock fragment) aspect of the rock or its fine-grained (clay) component. Greywackes are mostly grey, brown, yellow, or black, dull-colored sandy rocks that may occur in thick or thin beds along with shales and limestones. Some varieties include feldspathic greywacke, rich in feldspar, and lithic greywacke, rich in other tiny rock fragments. They can contain a very great variety of minerals, the principal ones being quartz, orthoclase and plagioclase feldspars, calcite, iron oxides and graphitic, carbonaceous matters, together with (in the coarser kinds) fragments of such rocks as felsite, chert, slate, gneiss, various schists, and quartzite. Among other minerals found in them are biotite, chlorite, tourmaline, epidote, apatite, garnet, hornblende, augite, sphene and pyrites. The cementing material may be siliceous or argillaceous and is sometimes calcareous.[1] In geology and geographyGreywackes are abundant in Wales, the south of Scotland, the Longford-Down Massif[2] in Ireland and the Lake District National Park of England; they compose the majority of the main Southern Alps that make up the backbone of New Zealand. Both feldspathic and lithic greywacke have been recognized in Ecca Group in South Africa.[3] Greywackes are also found in parts of the Eastern Desert east of the Nile.[4] They were an early object of geological study in Britain where the Geological Society was founded in 1807, and excited much public interest in geology.[5] Greywacke was interesting because it was found in many places in Britain and its occurrence in particular places was evidence of the pattern of geological strata that had been laid down.[6][7] UsesGreywacke stone has been used as a building material and a sculptural material across many eras and societies. Its oldest known uses date to the early third millennium BCE, in Egypt's early dynastic period. Its wide use in sculpture and vessels is thought to have been due to its fine grain size and resistance to fracturing, making it suitable for fine detail and intricate shapes.[4] Aside from its structural uses, greywacke stone (or molds taken from it) is valuable to practitioners of traditional motion picture miniature photography, because due to its unusually mixed nature, it remains looking natural when portraying a wide range of miniature scale ratios, from 1:1 to as high as 1:600.[8] Gallery

See alsoReferences

Other works cited

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Greywacke. |