|

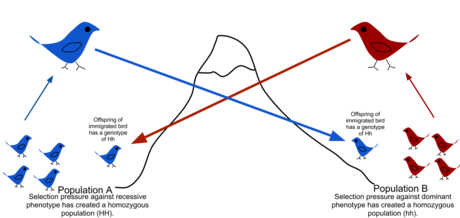

Gene flow In population genetics, gene flow (also known as migration and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent allele frequencies and therefore can be considered a single effective population. It has been shown that it takes only "one migrant per generation" to prevent populations from diverging due to drift.[1] Populations can diverge due to selection even when they are exchanging alleles, if the selection pressure is strong enough.[2][3] Gene flow is an important mechanism for transferring genetic diversity among populations. Migrants change the distribution of genetic diversity among populations, by modifying allele frequencies (the proportion of members carrying a particular variant of a gene). High rates of gene flow can reduce the genetic differentiation between the two groups, increasing homogeneity.[4] For this reason, gene flow has been thought to constrain speciation and prevent range expansion by combining the gene pools of the groups, thus preventing the development of differences in genetic variation that would have led to differentiation and adaptation.[5] In some cases dispersal resulting in gene flow may also result in the addition of novel genetic variants under positive selection to the gene pool of a species or population (adaptive introgression.[6]) There are a number of factors that affect the rate of gene flow between different populations. Gene flow is expected to be lower in species that have low dispersal or mobility, that occur in fragmented habitats, where there is long distances between populations, and when there are small population sizes.[7][8] Mobility plays an important role in dispersal rate, as highly mobile individuals tend to have greater movement prospects.[9] Although animals are thought to be more mobile than plants, pollen and seeds may be carried great distances by animals, water or wind. When gene flow is impeded, there can be an increase in inbreeding, measured by the inbreeding coefficient (F) within a population. For example, many island populations have low rates of gene flow due to geographic isolation and small population sizes. The Black Footed Rock Wallaby has several inbred populations that live on various islands off the coast of Australia. The population is so strongly isolated that lack of gene flow has led to high rates of inbreeding.[10] Measuring gene flowThe level of gene flow among populations can be estimated by observing the dispersal of individuals and recording their reproductive success.[4][11] This direct method is only suitable for some types of organisms, more often indirect methods are used that infer gene flow by comparing allele frequencies among population samples.[1][4] The more genetically differentiated two populations are, the lower the estimate of gene flow, because gene flow has a homogenizing effect. Isolation of populations leads to divergence due to drift, while migration reduces divergence. Gene flow can be measured by using the effective population size () and the net migration rate per generation (m). Using the approximation based on the Island model, the effect of migration can be calculated for a population in terms of the degree of genetic differentiation().[12] This formula accounts for the proportion of total molecular marker variation among populations, averaged over loci.[13] When there is one migrant per generation, the inbreeding coefficient () equals 0.2. However, when there is less than 1 migrant per generation (no migration), the inbreeding coefficient rises rapidly resulting in fixation and complete divergence ( = 1). The most common is < 0.25. This means there is some migration happening. Measures of population structure range from 0 to 1. When gene flow occurs via migration the deleterious effects of inbreeding can be ameliorated.[1]

The formula can be modified to solve for the migration rate when is known: , Nm = number of migrants.[1] Barriers to gene flowAllopatric speciation When gene flow is blocked by physical barriers, this results in Allopatric speciation or a geographical isolation that does not allow populations of the same species to exchange genetic material. Physical barriers to gene flow are usually, but not always, natural. They may include impassable mountain ranges, oceans, or vast deserts. In some cases, they can be artificial, human-made barriers, such as the Great Wall of China, which has hindered the gene flow of native plant populations.[14] One of these native plants, Ulmus pumila, demonstrated a lower prevalence of genetic differentiation than the plants Vitex negundo, Ziziphus jujuba, Heteropappus hispidus, and Prunus armeniaca whose habitat is located on the opposite side of the Great Wall of China where Ulmus pumila grows.[14] [failed verification]This is because Ulmus pumila has wind-pollination as its primary means of propagation and the latter-plants carry out pollination through insects.[14] [failed verification]Samples of the same species which grow on either side have been shown to have developed genetic differences, because there is little to no gene flow to provide recombination of the gene pools. Sympatric speciationBarriers to gene flow need not always be physical. Sympatric speciation happens when new species from the same ancestral species arise along the same range. This is often a result of a reproductive barrier. For example, two palm species of Howea found on Lord Howe Island were found to have substantially different flowering times correlated with soil preference, resulting in a reproductive barrier inhibiting gene flow.[15] Species can live in the same environment, yet show very limited gene flow due to reproductive barriers, fragmentation, specialist pollinators, or limited hybridization or hybridization yielding unfit hybrids. A cryptic species is a species that humans cannot tell is different without the use of genetics. Moreover, gene flow between hybrid and wild populations can result in loss of genetic diversity via genetic pollution, assortative mating and outbreeding. In human populations, genetic differentiation can also result from endogamy, due to differences in caste, ethnicity, customs and religion. Human assisted gene-flowGenetic rescueGene flow can also be used to assist species which are threatened with extinction. When a species exist in small populations there is an increased risk of inbreeding and greater susceptibility to loss of diversity due to drift. These populations can benefit greatly from the introduction of unrelated individuals[11] who can increase diversity[16] and reduce the amount of inbreeding, and potentially increase population size.[17] This was demonstrated in the lab with two bottleneck strains of Drosophila melanogaster, in which crosses between the two populations reversed the effects of inbreeding and led to greater chances of survival in not only one generation but two.[18] Genetic pollutionHuman activities such as movement of species and modification of landscape can result in genetic pollution, hybridization, introgression and genetic swamping. These processes can lead to homogenization or replacement of local genotypes as a result of either a numerical and/or fitness advantage of introduced plant or animal.[19] Nonnative species can threaten native plants and animals with extinction by hybridization and introgression either through purposeful introduction by humans or through habitat modification, bringing previously isolated species into contact. These phenomena can be especially detrimental for rare species coming into contact with more abundant ones which can occur between island and mainland species. Interbreeding between the species can cause a 'swamping' of the rarer species' gene pool, creating hybrids that supplant the native stock. This is a direct result of evolutionary forces such as natural selection, as well as genetic drift, which lead to the increasing prevalence of advantageous traits and homogenization. The extent of this phenomenon is not always apparent from outward appearance alone. While some degree of gene flow occurs in the course of normal evolution, hybridization with or without introgression may threaten a rare species' existence.[20][21] For example, the Mallard is an abundant species of duck that interbreeds readily with a wide range of other ducks and poses a threat to the integrity of some species.[22][failed verification] UrbanizationThere are two main models for how urbanization affects gene flow of urban populations. The first is through habitat fragmentation, also called urban fragmentation, in which alterations to the landscape that disrupt or fragment the habitat decrease genetic diversity. The second is called the urban facilitation model, and suggests that in some populations, gene flow is enabled by anthropogenic changes to the landscape. Urban facilitation of gene flow connects populations, reduces isolation, and increases gene flow into an area which would otherwise not have this specific genome composition.[23] Urban facilitation can occur in many different ways, but most of the mechanisms include bringing previously separated species into contact, either directly or indirectly. Altering a habitat through urbanization will cause habitat fragmentation, but could also potentially disrupt barriers and create a pathway, or corridor, that can connect two formerly separated species. The effectiveness of this depends on individual species’ dispersal abilities and adaptiveness to different environments to use anthropogenic structures to travel. Human-driven climate change is another mechanism by which southern-dwelling animals might be forced northward towards cooler temperatures, where they could come into contact with other populations not previously in their range. More directly, humans are known to introduce non-native species into new environments, which could lead to hybridization of similar species.[24] This urban facilitation model was tested on a human health pest, the Western black widow spider (Latrodectus hesperus). A study by Miles et al. collected genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism variation data in urban and rural spider populations and found evidence for increased gene flow in urban Western black widow spiders compared to rural populations. In addition, the genome of these spiders was more similar across rural populations than it was for urban populations, suggesting increased diversity, and therefore adaptation, in the urban populations of the Western black widow spider. Phenotypically, urban spiders are larger, darker, and more aggressive, which could lead to increased survival in urban environments. These findings demonstrate support for urban facilitation, as these spiders are actually able to spread and diversify faster across urban environments than they would in a rural one. However, it is also an example of how urban facilitation, despite increasing gene flow, is not necessarily beneficial to an environment, as Western black widow spiders have highly toxic venom and therefore pose risks for human health.[25] Another example of urban facilitation is that of migrating bobcats (Lynx rufus) in the northern US and southern Canada. A study by Marrote et al. sequenced fourteen different microsatellite loci in bobcats across the Great Lakes region, and found that longitude affected the interaction between anthropogenic landscape alterations and bobcat population gene flow. While rising global temperatures push bobcat populations into northern territory, increased human activity also enables bobcat migration northward. The increased human activity brings increased roads and traffic, but also increases road maintenance, plowing, and snow compaction, inadvertently clearing a path for bobcats to travel by. The anthropogenic influence on bobcat migration pathways is an example of urban facilitation via opening up a corridor for gene flow. However, in the bobcat's southern range, an increase in roads and traffic is correlated with a decrease in forest cover, which hinders bobcat population gene flow through these areas. Somewhat ironically, the movement of bobcats northward is caused by human-driven global warming, but is also enabled by increased anthropogenic activity in northern ranges that make these habitats more suitable to bobcats.[26] Consequences of urban facilitation vary from species to species. Positive effects of urban facilitation can occur when increased gene flow enables better adaptation and introduces beneficial alleles, and would ideally increase biodiversity. This has implications for conservation: for example, urban facilitation benefits an endangered species of tarantula and could help increase the population size. Negative effects would occur when increased gene flow is maladaptive and causes the loss of beneficial alleles. In the worst-case scenario, this would lead to genomic extinction through a hybrid swarm. It is also important to note that in the scheme of overall ecosystem health and biodiversity, urban facilitation is not necessarily beneficial, and generally applies to urban adapter pests.[25] Examples of this include the previously mentioned Western black widow spider, and also the cane toad, which was able to use roads by which to travel and overpopulate Australia.[23] Gene flow between speciesHorizontal gene transferHorizontal gene transfer (HGT) refers to the transfer of genes between organisms in a manner other than traditional reproduction, either through transformation (direct uptake of genetic material by a cell from its surroundings), conjugation (transfer of genetic material between two bacterial cells in direct contact), transduction (injection of foreign DNA by a bacteriophage virus into the host cell) or GTA-mediated transduction (transfer by a virus-like element produced by a bacterium) .[27][28] Viruses can transfer genes between species.[29] Bacteria can incorporate genes from dead bacteria, exchange genes with living bacteria, and can exchange plasmids across species boundaries.[30] "Sequence comparisons suggest recent horizontal transfer of many genes among diverse species including across the boundaries of phylogenetic 'domains'. Thus determining the phylogenetic history of a species can not be done conclusively by determining evolutionary trees for single genes."[31] Biologist Gogarten suggests "the original metaphor of a tree no longer fits the data from recent genome research". Biologists [should] instead use the metaphor of a mosaic to describe the different histories combined in individual genomes and use the metaphor of an intertwined net to visualize the rich exchange and cooperative effects of horizontal gene transfer.[32] "Using single genes as phylogenetic markers, it is difficult to trace organismal phylogeny in the presence of HGT. Combining the simple coalescence model of cladogenesis with rare HGT events suggest there was no single last common ancestor that contained all of the genes ancestral to those shared among the three domains of life. Each contemporary molecule has its own history and traces back to an individual molecule cenancestor. However, these molecular ancestors were likely to be present in different organisms at different times."[33] HybridizationIn some instances, when a species has a sister species and breeding capabilities are possible due to the removal of previous barriers or through introduction due to human intervention, species can hybridize and exchange genes and corresponding traits.[34] This exchange is not always clear-cut, for sometimes the hybrids may look identical to the original species phenotypically but upon testing the mtDNA it is apparent that hybridization has occurred. Differential hybridization also occurs because some traits and DNA are more readily exchanged than others, and this is a result of selective pressure or the absence thereof that allows for easier transaction. In instances in which the introduced species begins to replace the native species, the native species becomes threatened and the biodiversity is reduced, thus making this phenomenon negative rather than a positive case of gene flow that augments genetic diversity.[35] Introgression is the replacement of one species' alleles with that of the invader species. It is important to note that hybrids are sometime less "fit" than their parental generation,[36] and as a result is a closely monitored genetic issue as the ultimate goal in conservation genetics is to maintain the genetic integrity of a species and preserve biodiversity. Examples While gene flow can greatly enhance the fitness of a population, it can also have negative consequences depending on the population and the environment in which they reside. The effects of gene flow are context-dependent.

See alsoReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Gene flow.

|