|

Ernst Laas

Ernst Laas (born June 16, 1837, in Fürstenwalde/Spree; died July 25, 1885, in Strasbourg) was a gymnasium teacher, philosopher of positivism and education, and chair of philosophy and pedagogy at the University of Strasbourg. The insights he found in the history of philosophy and philosophies based on sensualism are key aspects of his scholarly work. BiographyLaas grew up as the son of the master tailor Johann Peter Laas (1807–57) and his wife Berta Ida Flora (1818–52), née Beil, in economically limited circumstances in Fürstenwalde, Brandenburg, Prussia. Ernst’s childhood was marked by various hardships, especially during the difficult years of 1846 and 1847 and the revolutionary period that followed. His father loyally supported the royalists, which led to retribution from the opposing party; they boycotted his work.[1] During this time as a young boy, Ernst and his younger brother had to collect firewood from the heath in his area after school each day to help their parents, who struggled just to provide the most basic food through their hard work. He quickly became acquainted with the seriousness of life and believed his fate was tied to his own personal energy he put into it. Due to his rough years growing up, Paul Kannengiesser has said that Laas "truly earned everything himself."[2] When Ernst completed his education at the local public school and was ready to choose a career, however, he faced the bleak prospect of becoming a waiter, an errand boy, or a tailor’s apprentice. But thanks to the support of the school principal Rector Gaedke, and General von Massow who admired his father’s loyalty to the crown, he was able to attend the Joachimsthal Gymnasium.[1][3]  Starting Easter 1851, he attended Joachimsthal’s Gymnasium in Berlin, later becoming a boarding student. Upon leaving school, Ernst noted that his personal struggles and experiences, combined with the educational methods used at home, led him to develop a shy and reserved demeanor which others found off-putting.[1] His noble patron died in December 1853, but his heirs continued his charitable efforts until Laas was able to support himself by taking a position as a private tutor.[2] He was eventually able to support himself financially from 1854 to 1856.  In October 1856, Laas enrolled at the University of Berlin to study theology at the request of his parents. But soon his interest soon shifted to study philosophy following the advice from Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg along with winning a prize with an essay on Aristotle. Laas’s association with Trendelenburg was a pivotal moment in his intellectual development. He attended Trendelenburg’s philosophical seminars from the time he entered the university until he earned his doctorate. He also enjoyed Trendelenburg’s personal favor and dedicated his first major work to him.[2] Yet it was not Trendelenburg’s unique metaphysical ideas that significantly influenced Laas, but rather his reformative views on the approach to philosophical study as a whole: his historical method.

Trendelenburg was known for his knowledge of the history of philosophy and taught in his lectures that a philosopher could learn much for their own thinking and about the thinking of others from the history of philosophy.[5] Through this "historical-critical"[4] method, Trendelenburg advocated for a deep, critical study to distill the enduring elements from the works of the past, which should then inform the true philosophical task of the present. Under Trendelenburg’s guidance, Laas' philosophical thinking initially oriented around Aristotle, and in his doctoral dissertation, he adopted a similar method to what Lessing later successfully employed.[1][2][6] That is, Lessing claimed that:

Laas thus following this method aims to critically extract the correct ideas from the judgments of his predecessors; a method that remained a characteristic feature of his entire approach to research. This approach also influenced his endeavor to search into the genesis of his subjects, guiding him in both philosophy and education.[2] Laas even stated that for all human institutions that have evolved from historical life, immersing oneself in their development is the only way to gain a clear understanding of their validity.[2][4] At Berlin, philosophy and cultural history were the main focuses of his university studies; in the seminars of Boeckh and Haupt, he developed the philological precision that marked his studies of Aristotle and Kant. Among his teachers was also Du Bois-Reymond. It was precisely during this time when the remarkable successes of the natural sciences were increasingly overshadowing philosophical speculation. As the significance of Hegel’s system waned, the esteem for empirical research rose, which Hegel had somewhat dismissed. This was especially true in German philosophy, particularly in the fields of psychology and epistemology where there was a growing interest in identifying and dissecting empirical facts (Tatsachen). These facts were the objects of experience found in the sciences, which many thought would likewise complement the new historical movement on its path to being a science.[2] And so, Laas was always on the lookout for a solid, fertile, naturalistic foundation, which was indeed greatly influenced by this empirical trend.[3] Thus, alongside his study of history, he delved into natural sciences. To be sure, while he did not conduct independent research in the natural sciences as he did in philosophy, education, and literary history, he nonetheless absorbed the results of scientific research with remarkable energy and gained a clear understanding of its methods.[2] This is demonstrated in his philosophical writings, which show a wide range of citations of the top scientists of Laas' time. He was, in any case, increasingly keen to emphasize the seriousness and sobriety of scientific thinking. The more firmly he grounded himself in this new scientific reality, the more rigorously he analyzed phenomena and immersed himself in their development, and the more he distanced himself from theories that twist away from the facts or try to leap to a “higher” understanding through some intellectual gymnastics.[2] Laas received his doctorate in philosophy December 5, 1859 with a dissertation on The Principle of Aristotle’s Eudaimonia and Its Significance in Ethics (Eudaimonia Aristotelis in ethicis principium quid velit et valeat). Laas regarded scientific psychology as the sole basis for ethics and praised Aristotle over Kant because Aristotle derived his moral directives from the specific nature of humans. He saw this as a valuable feature of his ideal of happiness, particularly because it could be realized on this earth. Here, then, one can see the beginnings of Laas's dispute with idealist thinking. He esteemed Aristotle's more empirical approach more highly than Plato's abstract suprasensory ethics based on ideas.[2] In 1860, he became a teacher of German, Greek, Latin, and Hebrew at the renowned Friedrichs-Gymnasium in Berlin and, in 1868, at the Berlin Wilhelm-Gymnasium. In 1861, he married Martha (1839–1919), née Vogeler and had five sons. His first major publication emerged from his teaching experiences—a guide on teaching German essay writing in the first class of the gymnasium which was published in 1868. Around the same time, he was appointed as a senior teacher with the title of professor at Wilhelms-Gymnasium.[3] He published further studies on German instruction in 1870 and 1871, which led to plans for a thorough revision of his first book. However, his appointment as a full professor at the University of Strasbourg in 1872, advocated by Trendelenburg, somewhat disrupted these plans. Nonetheless, he published German Instruction at Higher Educational Institutions in the same year and revised his earlier work on essay writing in 1876. In 1872, he received a full professorship in philosophy at the newly re-established Kaiser Wilhelm University of Strasbourg, a position he held until his death. Additionally, he published The Pedagogy of Johannes Sturm in 1872 and a small treatise on Gymnasium and Realschule in 1875.[1]  He was a well-informed and perceptive literary historian, as evidenced not only by many valuable comments on the essay topics he compiled from this field (found in his book on German essay writing), but also by his excellent study on Herder’s influence on German lyric poetry that was published in Die Grenzboten in 1871. Moreover, he was a top-tier educator and educational writer, an expert on the history of education, a theorist of style, and capable of using elevated, powerfully effective language when he wrote freely.[1] In his lectures, he initially dealt with literary and cultural-historical topics (including Luther, Lessing, Herder, and Goethe) and educational themes. He lectured on pedagogy during the time of Humanism and the Reformation and on educational theories in ancient and modern times. Although his early days as a professor exclusively focused on pedagogy, his lectures always included philosophical elements. That said, in his own field of philosophy, he was thoroughly familiar with every significant work of the past, especially those important in cultural history as well as contemporary studies. Paul Natorp has said that: "it’s hard to name a highly regarded book on a philosophical subject that he hadn’t referenced at some point in a way that shows he didn’t just read it but studied it deeply."[1] From 1878 onwards, he lectured exclusively on philosophy and continued to further educated himself in mathematics and the natural sciences.[8] His main philosophical works include Kant’s Analogies of Experience in 1876 and Idealism and Positivism, a three-volume series published between 1879 and 1884, among other publications and reviews, where he fought against the philosophies of Plato and Kant with a deep and open disdain. In the last decade of his life, however, Laas turned with increasing interest and an almost passionate involvement to the problems of the social sciences, law, and political theory. He strove with all his might to closely link philosophy with the empirical sciences. He primarily sought engagement with the rigorous sciences, and, in this, he was aware of his alignment with the goals of the Kantian school.[1] Like them, he saw figures such as Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton in the history of philosophy not just as representatives of the true model of the world but also as exemplars of self-reflection in scientific work. He believed that the “theory” of knowledge should above all else closely observe the “main stages of scientific discovery at work.” He acknowledged being inspired in this regard by Kantian thinkers like Whewell and Apelt.[1] Despite his critical stance towards theology and romanticism, Laas acknowledged the emotional dimensions of Christianity and the moral significance of art.[9] However, he came across as a man without emotion to many. One of his traits was that he was always quite stern and suppressed any emotional qualities about himself to others, however this aspect of his character was not permanent.[3] His friends have noted that he was a very kind man, which would only be shown in very infrequent moments. For Paul Natorp claimed in his obituary for Laas that:

His commitment to intellectual freedom and rigor made him a respected figure among his students and colleagues even as he challenged their views. But simultaneously, he always fostered an environment of critical evaluation and growth for his students. According to Paul Natorp, Laas was above all:

One of his students was the Viennese philosopher Benno Kerry (1858–1889) who published his literary remains after his death. According to Kerry, Laas published knowledgeable and detailed studies on the theoretical philosophy of his time, especially on Kant. Nonetheless, he was namely known for his three-volume chief work Idealism and Positivism (1879–1884) in which he advocated for the supremacy of positivism over idealist thinking. For Laas, the facts (Tatsachen) i.e. the objects of his positivism were the representations that people develop about the world either through “precieving” (warnehmen, Laas’s idiosyncratic spelling which he consistently used instead of wahrnehmen) or “feeling” (empfinden). He considered this sensualistic or positivistic approach to be philosophically superior and more productive than the idealistic approach of most of his contemporaries. In contrast to what he believed to be the problem with idealist philosophy, Laas always stressed that any fact he asserted could be verified, addressed, and developed further by anyone who wished to do so.[10] Laas’s positivist philosophy found much resonance in Strasbourg during his lifetime. But in the end, Laas philosophized independently and wasn't attached to any contemporary German schools of thought or had any followers, though he was in constant exchange of ideas with various thinkers of the 19th century. Nonetheless, his ideas became the source for controversial discussions on epistemology and moral philosophy. Laas, for example, asserted – similar to Hume, Mill, and Spencer, as well as in contrast to proponents of Kantian philosophy – that human reason is not capable of producing ideas and concepts that guarantee the objectivity of our knowledge and moral actions. He always stressed that people are always dependent on what they “perceive” and “feel.” However, Laas' association with the British Empiricists, French encyclopedists, and positivists was one of the reasons for his neglect given the prevalence of German nationalism. Laas highlights this nationalism at the end of the final volume of Idealism and Positivism:

This is further demonstrated when, in 1882 the Neo-Kantian Windelband was appointed to Strasbourg. On his view and the administration's of the University of Strasbourg, Laas’s positivist philosophy was a radical relativism or anti-philosophical sophistry that questioned philosophical values, such as objective knowledge and morality that must be shut down:

The concept of relativism in German philosophical discourse emerged not as a neutral descriptive term, but rather as a polemical tool in academic debates. And this contentious history can be traced to Wilhelm Windelband's influential 1884 characterization, where he dismissed relativism as "the philosophy of the jaded person who no longer believes in anything," and thus associating it specifically with urban skepticism and intellectual inconsistency.[12] And so, Windelband saw it as his “missionary task” to reassert traditional German, particularly Kantian and idealistic, philosophy in Strasbourg against Laas. We can see this in a letter Windelband writes in 1883:[13]

Windelband's treatment of Laas and positivism was largely driven by non-philosophical – essentially political – motivations. And it was these political factors that reduced Germany's first notably "positivist" philosopher and noted critic of Neo-Kantian a priori thinking to being remembered merely as a political figure rather than for his philosophical contributions. Moreover, an 1882 report from Strasbourg University's curator revealed political interference in academic appointments.[15] The document, addressed to the State Secretary of Alsace-Lorraine, discussed Wilhelm Windelband's appointment to replace Otto Liebmann as professor of philosophy:

The university brought in Windelband to succeed Liebmann, specifically to prevent the establishment of a Laasian school of thought and block it from gaining a foothold in Strasbourg for political and moral reasons. In 1884, Laas without knowing this was going on, nevertheless attacked Windelband’s Kritische oder genetische Methode? in his essay Ueber teleologischen Kriticismus.[16] In the conclusion of the third volume of his trilogy, Laas wrote about the philosophical and political significance of his investigations:

Yet, he did not regret having strongly emphasized the contrast between idealism and positivism. On the contrary, he considered some life and world views currently represented in the name of idealistic philosophy not just inaccurate but even “dangerous,” indeed “culturally dangerous.”[17]

But due to overwork, he suffered from health issues as early as 1877. Despite this, he completed his three-volume Idealism and Positivism in 1884, and barely rested until he sent off the last manuscript in September of the previous year. But a ten-day stay in the Black Forest was hardly sufficient recovery for him. In November, he became seriously ill with a kidney disease, which was compounded by asthma and insomnia. After a brief resurgence in the winter, his health rapidly declined.[1] He lost consciousness on July 23 and passed away on July 25 at 3:30 p.m. After his death, Laas’s positivist ideas were no longer discussed. Successors such as Avenarius, Mach, Ostwald, and Ratzenhofer virtually ignored him.[18] That said. Laas was mentioned in Eisler’s Philosophenlexikon[19] and in Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon.[20] But in the standard histories of philosophy of the 20th century, there are no detailed presentations of his ideas. Laas' grave is located in the Cimetière Saint-Gall in Strasbourg-Koenigshoffen (Section 5A-2-8).[21] Positivist philosophy1. Historical background Since around 1830, positivism, along with the rise of other sciences and the collapse of German Idealism, increasingly played an important role in philosophy.[22] The Neo-Kantians were busy updating and further developing their philosophical role model in line with the latest scientific developments. From their perspective, they contradicted positivist philosophers, for example, by arguing that judgments about facts are not possible without a priori presuppositions. This led to positivist-themed discussions among Neo-Kantians about Kantian ideas. For instance, there was debate over whether the a priori elements – such as Kant’s concepts and categories – should also be considered facts.[23] Laas regarded positivism as the “solely scientifically justified” philosophy. According to him, It was free from the “arbitrary absolutisms of speculative philosophy,” especially that of Hegel – as P. Jacob Kohn states in his dissertation on Laas’s positivism – and it employed the method of sciences practiced at the time.[24] Therefore, with his three-volume publication Idealism and Positivism, Laas attempted to establish a unified philosophy that also met “ethical” requirements, based on the “solid foundation of experience,” more specifically on the basis of sensory “perception.”[25] For this foundation, he used terms such as facts, sensations, experiences, and memories [Tatsachen, Empfindungen, Erlebnisse, and Erinnerungen]. In the first volume of his trilogy, Laas presented the general foundations of his positivism with interpretations of texts by Plato, Kant, non-Kantian philosophers, and philosophers close to positivism, such as Condillac from the early modern period. He launched a general attack on idealism, including Aristotle, René Descartes, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and especially Plato as its founder, as well as Kant. His purpose was to provide a remedy for the "discontinuity of philosophy"; that is, its failure to make progress over the centuries and its want of any clear standards.[26] The only way to put an end to this complaint was through a newer, critical method of the history of philosophy. In contrast to the old method, this method is directed not at the past, but “at the most immediate present and its current interests.”[27] This new method was primarily established on a synthesis between Lange’s History of Materialism[28] in the manner that elucidates foundational and general philosophical principles, and J. St. Mill’s tactic of “hand-to-hand fighting” used in the Examination[29] against Sir William Hamilton. It was also rooted in, however, by Leibniz’s and Trendelenburg’s perennial distinctions in the history of philosophy, and August Boeckhs’, Moriz Haupt’s, and especially Trendelenburg’s philology at the University of Berlin. Just as Trendelenburg attempted[30] by distinguishing between the “fundamental” aspects of a philosophy and its “derived” elements, so that "we might yet recognize the inherent organization, structure, and necessity within this diversity,"[26] for:

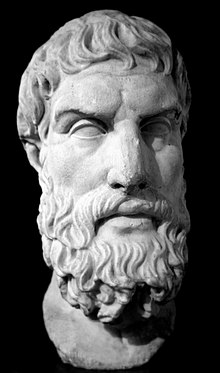

This new historical method revealed a fundamental dualism throughout the history of philosophy between the standpoints of Plato and Protagoras.[32] And this dualism swayed for centuries in favor of Plato, benefiting his followers at the expense of their opponents. This historical insight therefore led Laas – as the subtitle of Idealism and Positivism implies – to a “critical examination” of this dualism in order to see if idealism’s hegemonic victory was justified. After his critical examination, he concluded that it is now time to demonstrate that “there is no reason to abandon the ground of positivism,”[33] and only through positivism could “philosophy as a science… finally bear philosophical fruit.”[34]  When Laas referred to "positivism," he aligned with the traditional German interpretation of the term, associating it with Protagoras and the British empiricists rather than Auguste Comte's teachings, toward which he was generally indifferent or critical. More fittingly termed neo-empiricism in English contexts, Laas's theory focused on restricting knowledge to sensory data. It rejected the notion of an autonomous consciousness separate from perceptual content and denied the existence of objects beyond their perceptual interactions, thereby emphasizing the constant variability of perceived objects.[35] For Laas, positivist philosophy starts from sensory “perceptions” or facts (empirical objects), and rejects statements about non-sensory things along with idealist philosophy which – like Kant, for example – starts from ontological entities such as “reason” and ethical abstracts such as “ought,” which Kant thinks are present in human reason or understanding “before any experience” (a priori). But in contrast to the a priori, idealists only assigned a subordinate role to sensory “perceptions,” “sensations” and “facts.”[36][37] At first look, Laas observed it might seem as if the “transcendental philosophical turn… is vastly different from the Platonic view.” However, upon closer inspection, an “interesting kinship” emerges. Do not the “laws of understanding… have something of the paradigmatic character of Platonic ideas?” And doesn't the central role of the a priori forms align parallel to the Platonic ideas “towards the presuppositionless One and Good?”[38] Laas linked this idealistic approach to conceptual realism in logic, to a priori deductive rationalism in epistemology, and to both human spontaneous creativity and divine teleology in metaphysics. He viewed idealism as influenced by a mathematical pursuit of absolute knowledge and related it to the concepts of innate ideas and final causes.[35] Furthermore, Laas stated that idealistic philosophy is not capable of developing proposals that adequately respond to the current state of scientific development. Instead of starting from “facts,” or sensory “perceptions” like other sciences, idealistic philosophers are still constructing systems of suprasensory world knowledge – such as representatives of transcendental philosophy and Hegelian philosophy – intended to justify the certainty of scientific and everyday action. This certainty, as discussions among philosophers of the 19th century demonstrated, was only promised by Kant’s epistemology but has not yet been fulfilled.[39] Laas’s writings Kant’s Analogies of Experience (1876)[40] and Kant’s Role in the History of the Conflict between Faith and Knowledge (Berlin 1882)[41] provide detailed information on this. Laas saw himself as a successor to the philosophy of David Hume and John Stuart Mill, and he advocated for positivism or sensualism as a desirable common direction for the philosophy of his time. Although he recognized Auguste Comte as a founder of positivism, he found Comte lacking in pressing philosophical issues, such as statements on subject and object.[42] He rejected other ideas of Comte – including his doctrine of science – and distanced himself from Comte’s later religious ideas, which he considered “mystical and romantic.”[43] 1.1 Plato’s Theaetetus. “Man is the measure of all things,” argued Protagoras. Laas thought this statement to be one of the earliest foundations to his own philosophical approach. As the first volume of Idealism and Positivism makes clear, Protagoras is where all sensualist and positivist philosophy begins.[44] But as we only have fragments of Protagoras’s writings, we have to reconstruct his arguments from what remains. But thankfully, Protagoras’s philosophical account of knowledge is discussed quite heavily in Plato’s Theaetetus, where he gives an argument against his philosophy based on pure perception. While Laas thinks Plato gives some strawmans of Protagoras arguments and philosophical positions, as well as what be believes to falsely tying it to Heraclitus’s doctrine of “everything in flux”[45] – which led to a debate between his old student Paul Natorp[46] – he nonetheless acknowledges Plato’s philosophical gifts and literary talent.

In the dialogue Theaetetus, Plato tells us, through the mouth of the mathematician Theaetetus, that Protagoras argued that knowledge equals perception. And so Laas thinks that this Platonic dialogue, which is solely focused on experiential epistemology and at the same time tries to prove it false, gives the original roots of the principals which he counts as the basis for his positivist philosophy in its earliest and strongest form. But more importantly, Laas thinks this articulation of positivist philosophy has not deviated much from the modern version, while albeit widely misunderstood by the idealist in his day.

1.1.1. Protagoras’s argument for sensualism.Laas attempts to give a reconstruction of Plato’s argument of Protagoras’ sensualism in order to show how the underlying principles originated for his own philosophy. The reconstruction goes like this.[49]

Thus ultimately, if science takes shape as pure perception and experience, then it is nothing more than justified true belief.[49]  Laas thinks this argument, given by Plato’s reconstruction of Protagoras’s sensualist philosophy, exhibits the original principles of all empirical or positivist philosophy. “In this respect, the doctrine of modern sensualism aligns completely with that which Plato confronted.”[50] And he thinks that it is highly likely that if Plato were among us in modern times, “he would maintain his [idealistic] stance.” Because of this, he thinks modern proponents of positivist or sensualist philosophy have not deviated from these principals, even though some progress has been made. (E.g., Laas thinks this was done with David Hume and John Stuart Mill). 1.1.2 Plato's argument against sensualism.Likewise, Laas’s gives a summary of his reconstruction of Plato’s argument that a science [episteme/Wissenschaft] – like philosophy – could never be based on pure perception as Protagoras claimed.[51] For science or knowledge [episteme/Erkenntniss] are distinctly higher, more sublime, purer, and more spiritually enlightened than perception, which is influenced and shaped by experience. But humans capable of science or knowledge possess unique qualities not found in animals; they have an active, spontaneous mind and reason, not derived from passive states or mediated physically through perceptions generated by experience like other animals are. This is because human reason contains pre-existential, original knowledge in the form of intellectual concepts or “ideas” that transcend ordinary sensory experiences and give access to a supernatural reality. Likewise, the process of knowing these “ideas” is fundamentally a “recollection” of these intellectual concepts that are latent from birth, awaiting active rediscovery within oneself. Since true knowledge requires the human soul or mind to increasingly ignore the sensory input from the body; the mind must aim to become “pure” and free from sensory contamination to grasp pure objects with pure thoughts. Philosophy (dialectic) represents the purest form of this knowledge-seeking, free of sensory influence, where progress is made from ideas to ideas. Mathematics serves as a preliminary stage to this, as it abstracts from sensuality and orients the soul toward pure thinking and truth. Although sensory experiences may prompt reflection, they are mainly useful in pointing out contradictions that need to be resolved intellectually, not perceptually. True knowledge comes from an active recollection and contemplation of these a priori ideas, which are fundamentally separate from the passive, animalistic, and physically mediated state of perception. Thus, science or knowledge are not perception because it involves a distinct, higher form of cognitive activity that engages intellectual concepts, which are pre-existential and not derived from sensory experiences.[51] With that said, Laas thought the impact of Plato’s argument in the Theaetetus against anti-sensory philosophy was too severe and pervasive, shaping our thoughts and cultural significantly for the worse.[52] For one, Laas critiques the development of Platonism for not maintaining a consistent, scientific progression, as he notes that its initial developments led to excesses in asceticism and mysticism, which in the end diluted its philosophical richness. Secondly, Laas argued that modern Platonists often focus selectively on Plato’s doctrines, while rarely seeking to revitalize the entire philosophical framework. For this reason, Laas tried to point out a tendency within Platonism: it drifts towards non-scientific realms of myths and pious intuitions, while simultaneously blurring the lines between serious philosophical inquiry and mere images.[53] Building on this, Laas discusses how Descartes and Leibniz adapted and modified Platonic thought. On the one hand, Descartes emphasized the “natural light” of reason as a criterion for truth, thereby defining humans as thinking substances with innate ideas while separating the human mind from the body. Leibniz, on the other hand, took idealist philosophy further by merging Platonic and Cartesian elements, which in the end advocated for a sophisticated rationalism that recognized innate ideas as inherent properties of the human soul, setting the stage for Kant’s critical examination of rationalism in response to empiricism. As a result, Kant sought to redefine the boundaries of “pure reason,” thereby limiting its domain to the field of possible experience and establishing a priori knowledge as foundational to human cognition. Laas thought that Kant’s philosophy represented a significant shift in idealism: the transcendental shift. For Kant argued for a form of a priori knowledge and principles as essential to understanding, which Laas thought reflected Plato’s influence yet also marking a departure into new philosophical territory. 1.2 The 5 motifs of idealism.Laas, in his attempt to argue against idealism, identified five motifs that idealist philosophy utilized in order to attack sensualism/positivism to support their standpoint through out Western history.[54] These are:

2. Sensualistic positivismBy professing anti-Platonism, Laas does not want to defend everything that could fall under it,[58] but only what he calls positivism. Positivism is namely:

Thus “the positivist… is at the same time a sensualist.”[60] Sensualism is an approach for the explanation of phenomenon within our conscious life that begins with the given. In Laas' own words:

In short, Laas fundamentally viewed the possibilities of philosophy differently than the idealists Plato and Kant. The latter had claimed that every person possesses a mental faculty called reason whereas wants to begin epistemology and ethics with solely with what we experience and perceive. According to Laas, historically speaking, Kant had merely replaced the previous scholastic metaphysics with a different term. Sensualists or positivists deny entities such as God and reason, and assert that all thinking, judging, and representations are fundamentally based on “sensory sensations” or “perceptions” or “facts.” For Laas, contrary to all experience, idealists claim that the faculty of “reason” determines thought and action and can judge everything, even what a person has not yet experienced. Moreover, positivists think sensually and base their arguments exclusively on the sensibly experienceable, on facts [Tatsachen]. These facts, unlike the “non-sensible” transcendental categories and Platonic ideas, are the empirical objects that are accessible to everyone which stimulate independent thinking and action. The sensibly experienceable, or the world of matter and the natural sciences, can be sufficiently explained through mutually conditioning factors. As Hume had made clear, it is questionable to construct causal connections and habitually hold them to be “true.”[62] From an idealistic perspective, it is objected that the sensibly experienceable does not serve as a suitable basis for investigation because it continuously changes. This applies also to psychic phenomena, or our “perception,” thinking, judging, feeling. Everything is in flux, as Heraclitus is said to have noted. This statement prompted Plato to invent eternal, unchanging ideas. Kant, spurred by Hume’s skepticism, claimed a priori concepts free from experience to create certainty.[63] For this reason, Laas concludes that both philosophers have left people with a faithful trust in their idealistic assertions, instead of advising them to verify these claims based on facts.[64] For a positivist, “change” or “transformation” is an empirical fact that philosophy must accept and investigate if it aims to provide scientific guidelines for thinking and acting. Laas thought that the development of science in the 19th century shows that despite all change and transformation, and despite all errors, there are useful research results. But idealistic claims of absoluteness ignore this.[65] According to Laas, from our “perceptions,” memories and representations emerge, that is, “psychic realities” with which we can conduct scientific research.[66] Laas also counted among the changes in the world the changes or variations in “perceptions.” People do not only perceive facts differently individually. Even what is supposedly the same is perceived differently at different times. Laas thought this is one of the strongest and most universally understandable objections to idealism, which assumes that there are ideas or a reason within humans that enable consistent knowledge. Similarly Johann Ulrich from Jena criticized this, one of the first and well-known interpreters of Kant and a contemporary of Kant. Protagoras expressed this everyday experience or fact with his statement that “Man is the measure of all things.” Plato, interpreting Protagoras, added in Theaetetus 160c the idea: “Things are for me as they are for me, and for you as they are for you.”[67] But for Laas, if the entirely individual perspective of each person were a correct fact, then any idealistic attempt would become unnecessary – whether through any kind of doctrine of ideas or even more sophisticated transcendental philosophical constructions – to transform “perceptions” into something objective. He will show on the following “pages” that although something similar could succeed in positivism, it would be in a completely different way than usual.[68] Laas, keen to avoid the pitfalls of "monstrous" subjective idealism, along with "skepticism," "frivolity," and "trivial common sense philosophy," started to lean towards a neo-Kantian perspective by advocating for an ideal or complete consciousness.[1][35] Because, by echoing Mill’s assertion that the aggregate of actual sensory objects falls short in constructing a coherent world, Laas argued that the world encompasses all conceivable contents of perception, guaranteed to an ideal consciousness, which philosophy aims to reconstruct.[35] He asserted that while objects (facts) are independent of consciousness (albeit not perception), this includes the ideal consciousness, thus preserving the feasibility of scientifically investigating the physical world. This approach was meant to guard against "skepticism," despite acknowledging the world's relative and fluctuating nature. At the end of the first volume of his historical-critical analysis in Idealism and Positivism, Laas’s described his positivism as an idealism “entirely of this world.” The ideas [Ideen] he uses, however, are self-made and have their roots in sensory perceptions. They do not come from pure reason or the Platonic realm of ideas, but rather from very practical desires and human needs for improving society.[69] 3. Correlativism.The term correlativism [Korrelativismus] has disappeared from philosophical discussion for more than 100 years. The fundamental meaning associated with it is found in the correlation of measurement variables and functions in mathematics and statistics. For Laas, correlativism means the intertwined relationship between subject and object in perception. This theory subscribes to three core ideas. Firstly, that perceptions are the result of pairs of interconnected, dynamic processes that are constantly in flux. Secondly, because of this continual change, perceptions themselves lack permanence and are always in a state of “becoming.”[70] Lastly, all perceptions exhibit an inseparable connection between the subject (the perceiver) and the object (the perceived), such that neither can exist without the other. While Laas “won’t discuss the Protagorean origin of the first two ideas,”[70] he believes that “we can attribute the third to the sophist.” This third idea is framed as a significant milestone in the development of sensualism, as it “represents an insight of fundamental and far-reaching importance,”[71] and “if it first arose in Protagoras’ mind, this brilliant ‘sophist’ deserves more respect in the history of philosophy than he has received,” regardless of the historical accuracy of Plato’s accounts, since they sometimes portray Protagoras in a critical light. Likewise for Laas, correlativism distinctly rejects the notions of subjectivism and idealism that were put forward by philosophers like Descartes, Berkeley, and Kant, where they argued against this idea that perceptions are merely subjective experiences or modifications of consciousness. Instead, Laas presents correlativism as a theory of “subject-objectivism,” where the existence of objective perceptual content is inherently tied to a perceiving subject, and vice versa. This is because, for Laas, the perceptual world is not produced by the “I,” or any synonymous terms like subject, consciousness, mind, intellect, etc. Perceptions are not a spontaneous creation or reaction of the inner self, for “to be a perceiving subject without perceiving something is impossible. In other words, consciousness, soul, or self, apart from sensory perception, is nothing.”[72] Moreover, perceptual objects (what we see, hear, etc.) are not subjective modifications or states of consciousness; they are the most original and independent forms of objects, distinct from states of consciousness. Consciousness cannot exist without perceptual content, and perceptual content always implies the presence of a perceiving subject. The subject (the perceiver) and the object (the perceived) are inseparably linked. Thus correlativism:

3.1. Event rather than substanceSimilar to Hume,” Laas sees “in the ‘world’ nothing more than a collection of sensory or perceptual realities and possibilities.” Beyond these realities, there is for him “no object ‘in itself’ and no transcendent ‘matter.’”[74] On the other hand, for idealists like metaphysicians and rationalists, the world consists of two substances, namely “matter” and “mind.”[75] Laas considers only “subjective states (feelings) and sensory content (sensations).”[76] Similarly, this is done by the anti-metaphysicians Richard Avenarius and Ernst Mach after him. Contrary to Kantian philosophy, humans do not need “transcendental forms of intuition” for the concept of an extended world. The representation of extension, according to Laas, is acquired from birth through the senses. Thus, everyone can inherently conceive of extension and space, “in terms of the position of his body and his living conditions. These representations never leave them throughout their life.”[77] 3.2. Experience of wholenessLaas always bases his theory of knowing on physical events, while Kant relies on rational definitions. This accounts for the marked difference between their theories knowing. For Laas, the subject-object relation is “correlative” [correlative/korrelativ] That is, the subject and object are not – as Kant thought – absolute, independent “existences,” but “rather both are correlative phenomena: they are ‘moments’ of an ‘experiential whole.’”[78] Thus, the self has no “transcendent existence.” The self lives “through the actual and conceivable connections of the present moment, the experienced and the experienceable.” Therefore, “the present moment is the most certain; and in the same is always the correlation… of self and world: neither of these moments exists without the other.”[79] Subject and object together generate “the object of perception, on the one hand, and perception” as a psychological state on the other. The generating processes are in constant flow and have “an existence that varies from moment to moment.”[80] They are “inseparable twins, stand or fall together.” However, Laas states that his theory of knowledge is not “subjectivism anymore, but… subject-objectivism [Subjekt-Objektivismus]; it is, strictly speaking, not relativism, but correlativism.”[81] With his correlativism, Laas responded to the allegation by the idealistic philosophy of his time, which claimed that positivism was merely “a new edition of egoism or solipsism.” Laas counters that critique with the tools of idealist epistemology, arguing that positivist facts are merely mental representations of consciousness with no connection to the transcendent or transcendental object.[82] Laas refutes this accusation with references to the entirely different framework of his philosophizing—among other things, for him, the separation of mind and body is not phenomenally demonstrable. His focus is on the individual and society, that is, “on the present and its current interests.”[83] For these, mental facts, representations, and “perceptions” that people use are axiomatically indispensable.[84] One of his interpreters, Dragischa Gjurits, observes: “No matter how we turn it, the fact remains that we can never epistemologically escape from correlativism.”[85] Gjurits further notes that correlativism is the central axis of all of Laas's philosophical views around which they revolve.[86] 4. Epistemology In the early modern era, scientists had established epistemology as a fundamental discipline of science. According to Richard Rorty, in Locke’s time, it was an empirical endeavor aimed at justifying the new sciences that had emerged since the Renaissance, “from below” through the senses. Previously, the scholastic schools had justified the sciences “from above,” from God and reason. Epistemology, as Locke conceived it, was meant to be a “natural philosophy”: scientific research should clarify what the human mind can know, judge, and understand.[87] About 100 years after Locke, Laas thought that the epistemological undertaking in Germany was once again directed by idealistic, Kantian, or post-Kantian ideas. For these idealists, or all “anti-sensualist tendencies” as Laas also called them, all representations, ideas, and actions arise from the intellectual capacity they call reason. Reason guarantees the objective validity of philosophical statements when they are formulated in accordance with correct logical laws in conjunction with a priori concepts. Reason not only enables philosophers but all people to make correct judgments about any possible experience as well as about non-experiential matters.[88] Laas observes that sensualists like Protagoras, and positivists like himself, consider these idealistic assertions to be unfounded. From his perspective, they are, among other things, a result of the Platonic construct of “absolute certainty” and “innate ideas.” According to the scientific standards of the 19th century, for Laas, this approach should now be considered outdated.[89] In terms of human action and thought, Laas even refers to this idea as a “harmful error” because it ultimately ignores what people perceive. No demand of reason can change the fact that the facts (“perceptions”) are as they are.[90] Positivists, like Berkeley, Locke, and Hume, start from “perceptions” and accept that what people “perceive” is relative and changeable. Unlike idealists, however, positivists maintain that this reality can be scientifically addressed.[91] 4.1. The facts of human knowledgeIt is part of every person’s experience to have repeatedly found that the continuity of our “perceptions,” or our thinking, is constantly interrupted. We notice that the impressions of different senses mingle and connect. We experience that memories, fantasies, and fragments of thoughts intervene in every thinking process. Yet, people have always been capable of conducting science because, according to Laas, they have no problem with their "perceptions," judgments, and feelings constantly changing.[92] In everyday life, people handle their “perceptions,” or changes in facts, in the following tried and tested ways:

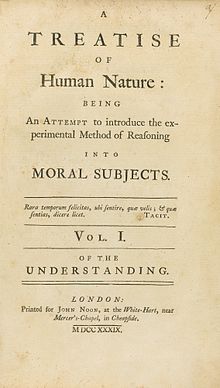

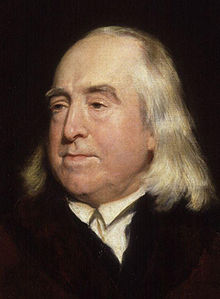

4.2. Scientific knowledgeScience picks up all perceptions that are more or less superficial and random or serve only the individual, and then scrutinizes them. By systematically observing, either directly or through the intermediary of the medium, scientists try to “establish scientific fundamental facts.”[95] Scientists live with probabilities. They must assume that there is no certainty. “They are accustomed to starting with the provisional and progressively searching for the definitive.” For this purpose, they infer law-like changes in their research subjects from changing relations. Under the current scientific conditions, they unify the different individual perspectives into a consistent representation of the specific object.[96] For Laas, this does not affect “formal truth.” It compares things under abstract conditions – for example, using mathematical tools – which are concretely incomparable. Moreover, science can hypothetically or fictitiously dissolve “perceivable” things (e.g., atomic theory). Private and scientific evaluations of facts are results of “complicated chains of thought.” They are based on arbitrary judgments of taste or on presumed effects. Positivists assess research outcomes according to the highest common utility. However, even they cannot specify what this actually consists of. What benefits everyone must therefore be continuously investigated together.[97]  Scientifically fruitful would also be all distinctions that improve our abilities to “navigate the world of diversity,” understand its laws, and make predictions. Each conceptual differentiation and categorization serves the development of the sciences. The idea of exploring human capabilities – because they are fundamental conditions of all sciences – was also suggested by David Hume in his Treatise on Human Nature to all modern philosophers.[98] The similarity with Hume’s phenomenology of the human mind, particularly of human “perceiving” through “impressions,” is reflected in the epistemology of Laas. The terms and issues used by Laas are not only linguistically related to Hume's sensualist thinking but are likely comparable in substance as well.[99][100] 4.3. The foundations of his epistemologyLaas bases his epistemology exclusively on “sensations.” From these, both from his own perspective and from the viewpoint of other sensualists like Locke, Comte, Hume, and Condillac, representations and facts develop, which guide human orientation.[101] Reason plays a subordinate role for Laas. He considers it – as Hume had phrased – to be “the slave of sensations.” It primarily serves logical thinking. But an epistemology that aids human action is not made possible through reason. From a positivist perspective, “sensations” are fundamental. Neurophysiologically, they are characterized as “physical accompaniments” of knowing [Erkennens].[102] The terms “sensations,” “perceptions,” and “facts” are used by Laas interchangeably. They do not denote “knowledge” [Erkenntnisse] but rather what precedes and conditions “knowing” throughout life. According to Laas, modern idealistic epistemology, whose main proponent Kant with his transcendental philosophical version of rational idealism that starts from something secondary, namely a genetically later element, is “reason,” and declares it the spiritual “court of justice” [Gerichtshof] that evaluates all knowing.[103] “Pure reason,” according to Kant, supplies all the means of knowledge, with the subservient participation of sensory events, to recognize the world.[104] However, he overlooks that the world is always present to us through “sensations of temperature, touch, and pressure.”[79] In Laas's view, Kant acted as if the mind were present to consciousness as a “substance”; and as if the self were more present than the constantly present sensations of touch and pressure on our skin.[105] Accordingly, in the first preface of the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), he devalued the “physiology of the human mind” conducted by Locke in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) because Locke had derived it from the “rabble of common experience.”[106] In 1877, a reviewer of the Jena Literary Gazette[107] recommended to the Kantian adherents of the a priori of his time to confront this “vigorous attack on the transcendental hypothesis.” It might be, the reviewer suggested, that Laas’s critique marks a “turning point in the development of the theory of knowledge, that is currently being worked on so much.”[108] The prevailing theory of knowing seems to have “perceived” this possible “turning point” as a “blind spot” of its own knowledge. For unlike Laas, it insists inappropriately that subject and object are not only separated but that the object must in every respect be an “independent entity.”[109] 5. Positivist ethicsThe improvement of society was also the guiding principle of the ethics developed by Laas. It is a religion-free “morality brought down to earth.”[110] He considers it impossible that various religions can contribute to peaceful coexistence. Additionally, matters of faith are not scientifically answerable.[111]  From his perspective, it is unnecessary for citizens to belong to a religion. Instead, it is essential to guide everyone to act morally. A morality valid for all could only be developed collectively, as individuals would be overwhelmed by this task.[112] His ethics follow the “eudaimonistic” principle.[113] He characterizes this principle with the idea that one can lead a fulfilling life, both individually and together with others. The specifics of this concept for his time, including prospects for possible further developments, are the subject of his “ethics.” 5.1. The exclusion of existing moral conceptsLaas claims that current and past moral concepts lack a philosophically and logically sound foundation and remain stuck in the moral self-evident truths of their respective times. This applies to all views that assume human innate nature enables people to make morally correct decisions and act accordingly, as was the case for Aristotle and philosophers who followed him.[114] Similar errors among Christian philosophers have led to the assumption of a “purely ideal human” who could act morally correctly if only he wanted to, and therefore could also make morally right decisions for social policy. This applies, for example, to Herder, Fichte, and Schiller. Laas notes that this claim – because of its fundamental ambiguities – is not suitable for community life and carries the potential for inciting unforeseeable social conflicts.[115] Laas also attests ambiguity to the “instinctive moral concepts” of English thinkers, such as the Platonist Shaftesbury and the Enlightenment philosopher Hutcheson. For Laas, they merely observed that moral judgments “occur with instinctive immediacy.” And so the conditions under which these moral judgments operate remain forever hidden. According to Laas, this means individuals are neither enabled to control their actions nor placed in a position to reflect on them.[115] Kant's moral approach fails due to the unproven assertion that reason, autonomous and free from immorality and combined with the will, makes ethical action possible.[116] Kant does not clarify how people can be induced to moral actions, except to demand that these be compulsorily made a duty, thereby incorporating Christian beliefs and convictions. He uses terms like “transcendental freedom” and the formal Golden Rule, which express Platonic-Aristotelian views. However, Laas points out that the moral law is founded “in the culturally acquired, in the feelings of solidarity and justice,” and not in the unprovable pure reason.[117] 5.2. Ethics as a wisdom of life.Laas characterizes his ethics as “practical wisdom for life.” This wisdom “balances the pleasure and utility of the individual with the pleasure and utility of all others in such a way that it produces the highest bliss for the whole.” Thus, Laas describes both the process and the current state of individual and societal ethics. Moral action unfolds human skills and follows maxims that arise from human experience and guarantee collective happiness “with probability.” Corrections are made that, according to human judgment, are likely to improve pleasure and utility. Together, possible consequences of each decision are considered in order to continuously advance the moral action of all people.[118] 5.3. Forerunners to his ethics Laas cites the moral theories of the Epicureans and Jeremy Bentham as models for his ethics. According to Laas, the Epicureans laid the groundwork for his positivist ethics. For the Epicureans, ethics is committed to the pleasure of life. It functions socially as “creation of needs” and “agreements of utility” to protect people from harming each other. Thus, morally correct actions are those that protect the individual from harm and benefit society. If moral laws are deficient in this respect, they must be improved.[119] The most successful further development of Epicurean ethics, Laas claims, was achieved by Jeremy Bentham. He expanded the sympathetic and friendly impulses of the Epicureans into a “universal philanthropy.” This individualized ethics, which Bentham calls “private ethics,” are realized in the context of the development of social policy and legislation.[120] With that said, Laas considers Bentham’s idea that ethically good actions naturally align with the prudently calculated, as if by itself, to be a mistake. Laas thinks that contemporary morality can build on the values and formulations of history. Because in general and in essence, history had the right thing in mind and, in the majority of cases, it indeed was right. But also, in contrast to Bentham, Laas adheres to the concept of duty “You shall!”[121]

5.4. Ideals of His EthicsLaas defines morality, or ethics, as the "science of ideals" of his practical wisdom for life. These ideals are the highest good, the highest duty, and the highest virtue.

It is the task of both private and public education to develop this behavior without coercion. The morally valuable aspects, moral duties, and virtues are substantive tasks that people must solve together.[112] Morality is a social function. According to Laas, it is shaped by the demands of others and the needs of each individual.[122] The starting point for the implementation of his ideals is therefore the respective valid morality or the practiced moral and self-evident behaviors. They must be examined to determine the extent to which they serve both individual and common interests. Moral education must not only be free of violence and coercion, but furthermore, if everyone is to respect moral rights and duties, then everyone must individually also have a say in the matter.[123] 5.5. The objectivity of moralityThe designation “objectively valuable” applies only to those values that “lie in the well-understood general interest of a larger number of sentient beings.” This “very simple idea” establishes “the indissoluble unity of duties and rights” and is derived exclusively from human “needs and interests.” For example, a truly objective moral value is the desire of all people to limit the despotism of individuals and groups.[123] Laas’s definition of “objective” follows his view that subject and object are inseparably connected. He has called this Correlativism [Korrelativismus]. Objectivity in this sense is a functioning, harmonious subject-object relation. Laas also refers to this type of objectivity as “subject-objectivism.” With this, he also clarifies the connection he sees between his notion of objectivity and that of Protagoras. A similar concept can be found in Arthur Schopenhauer, for whom “will” and “representation” provide a mutually enabling foundation for comprehending and forming the world.[124][125] 5.6. Morality needs collaboration.The moral development of both individuals and society depends on the cooperation of everyone working together. Small, but manageable cooperation provides the initial important impetus for this. The more people come together in a well-organized cooperation and feel solidarity, the greater the average prospect of increasing happiness for individuals. The highest form of cooperation is the entire human race working together, including the animals “trained and bred” in order to meet our needs. Social organizations continuously work on the progressive development of a fulfilling life (eudaimonia) for all. Because of this, they should be supported through the development of social policy techniques: “It is the task of social policy technique to bring to light and implement the legal and duty demarcations necessary to enhance the common good.”[126] Moreover, he denied the identification of self-interest with egoism and held, rather, that self-interest dictates the performance of duties and the fulfillment of demands and expectations imposed on the individual by his environment. In this way, ethical values are the consequences of a particular social order. They acquire validity when they are judged, in the long run and by a considerable number of people, to be worthwhile.[35] 5.7. Morality has history.The specific goal of the prevailing morality is subject to societal development, which pursues the highest satisfaction “without knowing what enables this satisfaction.” Therefore, the current state of moral culture consists “of attempts to delineate freedoms and necessary duties from each other, so that overall an increase in happiness for many seems attainable.”[127] Only through the course of historical development will people improve their sense of the generally beneficial and their understanding of the best means for achieving it, so that sufferings decrease and joys increase.[128] Reform of the language educational system1. Education and cultural developmentLaas advocated for thorough reforms of all existing higher educational institutions, especially the gymnasia. He noted that these institutions still clung to the centuries-old, scholastic form of education which believed it could do without any connection to real life and instead practiced the exclusive imparting of theoretical book style knowledge. He published his tested ideas in 1872 in Der deutsche Unterricht auf höheren Lehranstalten. He emphasized that his reform proposals were overdue consequences of changed socio-political conditions. This resulted in a book that he had painfully lacked as a young teacher.[129] 2. Modernization of language educationFrom Laas's perspective, the outdated curriculum concepts and content arose from the fact that the curricula and syllabuses still valid in his time had already been developed in the 16th century. The reformer Melanchthon had established the contents and methods of teaching to meet the requirements of that era. As a result, Latin remained a subject and the language of instruction, just as it had been in the Middle Ages. At the time, this corresponded to the importance of Latin as the language of science and as the language of communication throughout Europe. These conditions no longer existed in Laas’s time. National languages had replaced Latin in the sciences, social interactions, and literature. 3. The Changing role of Latin in educationBut when Laas was alive, the old curricula and syllabuses had not yet been changed. This led to criticism and discontent from many involved in educational instructional design regarding the methods and content used. The outdated curricula primarily prevented the higher educational institutions from evolving into general educational institutions that should serve the learning needs and interests of the people of their time. It was mostly the students who wanted to pursue a teaching career that benefited the most.[130] However, Latin was no longer the language of the scientific and educated world.[131] And so, Laas felt that it was no longer appropriate that students failed their final exams due to a specific number of errors in Latin grammar tests. 4. To interpret instead of imitateHe proposed extensive and, in the discussions of his time, controversial changes: primarily a reduction in grammar and formal style exercises in the classical language subjects. His final suggestion specifically addressed the teaching practice of having students present their own formulated and memorized texts as “speeches” before the class. Laas considered these “speeches” a waste of time due to their low quality of their content and minimal learning incentives.[132] Instead of such formal content, the focus should primarily be on the substantive interpretation of ancient writers, including texts by contemporary German-speaking authors. This way, students could also learn to write genuinely independent texts. Likewise, Laas was focused on the personal development of the students, which was not adequately fostered under the existing curricula.[133] He had already elaborated on this idea in 1868 in Der deutsche Aufsatz in der ersten Gymnasialklasse (Prima.) and supplemented it with additional material and resources. Influence One of his most influential students was the Neo-Kantian philosopher Paul Natorp. Natorp wrote in his obituary for Laas that his approach to education – emphasizing independence over imitation – left a lasting impact on his students and the philosophical community.[1] Natorp became a student and worked with Laas on achieving a coherent version of positivism when he went to Strasburg in mid 1870s. But Natorp ended up eventually going against his positivism. “Just when I thought I had grasped the ‘consistency’ of positivism that we had long sought together, it then appeared to me as an illusion. And so from that point on, the historical progression from Hume to Kant now seemed justifiable to me.” In the end, despite the rigorous mentorship, differences in philosophical outlook eventually led to the cessation of a long-standing collaboration with the fellow philosopher, described by Laas in a letter to Natorp as a divergence of “natural destiny.”

Laas then pointed Natorp towards the Kantians from whom he believed he would gain more support than from him. Natorp's move away from positivism struck Laas as “almost elegiac.”[1] He overcame that “elegiac mood” through reflection which best characterizes the spirit in which he worked: “education towards independence is more dignified than training imitators.”[1] Nonetheless, Natorp credits Laas with inspiring his commitment for the essential integration of historical and specialized research within philosophy. In fact, Natorp views himself as both a disciple of Laas and an adherent of Hermann Cohen's perspectives, finding joy in the synthesis of these influences.[1] Likewise, Natorp believed he and Laas were more similar in thinking then what Laas believed:

Laas's historical-philosophical method advocates for a methodical examination of the origins and development of philosophy as a science, using scientific viewpoints and philosophical theories to uncover underlying systematic laws (for Laas these laws are psycho-genetically developed).[134] This approach seeks to reveal the inherent order within what might initially appear as chaotic philosophical progressions. Characterized by Natorp as a form of "constructing" history, this method is therefore based on the premise that understanding the "syntax" of a science prevents its history from appearing disjointed.[1][135][30] WorksHis chief educational works were Der deutsche Aufsatz in den ersten Gymnasialklassen (1868), and Der deutsche Unterricht auf höhern Lehranstalten (1872; 2nd ed. 1886). He contributed largely to the Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie (1880–82); the Literarischer Nachlass, a posthumous collection, was published at Vienna (1887).[136] None of Laas work’s have been translated into English. Here is a list of his works taken from Paul Kannengiesser’s obituary for Laas and some additional texts Kannengiesser missed.[137] 1. Philosophical and Historical Writings.Books and Articles.(1859) “Eudaimonia Aristotelis in ethicis principium quid velit et valeat.” [“The Principle of Aristotle’s Eudaimonia and Its Significance in Ethics.”] PhD diss. University of Berlin. Digitized. (1863) Aristotelische Textesstudien. [Studies in Aristotelian Texts (Concerns the first four books of Physics)]. Programm des Friedrichs-Gymnasiums, Berlin: Gustav Lange. Digitized. (1876) Kants Analogien der Erfahrung. Eine kritische Studie über die Grundlagen der theoretischen Philosophie. [Kant’s Analogies of Experience. A critical Study of the Foundations of Theoretical Philosophy] Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. Digitized. (1879) Idealismus und Positivismus. Eine kritische Auseinandersetzung. Erster, allgemeiner und grundlegender Teil. [Idealism and Positivism. A Critical Examination. First, General and Foundational Part] Vol. 1, Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. Digitized. (1880) “Die Causalität des Ich.” [“The Causality of the I.”] In: Viertel Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie, edited by Richard Avenarius, pp. 1–54; 185–224; 311–367, Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland). Digitized. (1881/1882) “Vergeltung und Zurechnung.” [“Retribution and Imputation.”] In: Viertel Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie, edited by Richard Avenarius. 1881: pp. 137–185; 296–348; 448–489; 1882: pp. 189–233; 295–329. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland). Digitized: 1881; 1882. (1882) Idealismus und Positivismus. Zweiter Teil: Idealistische und positivistische Ethik. [Idealism and Positivism. Part Two: Idealist and Positivist Ethics] Vol. 2, Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. Digitized. (1882). Kants Stellung in der Geschichte des Konflikts zwischen Glauben und Wissen. Eine Studie. [Kant’s Position in the History of the Conflict Between Faith and Knowledge. A Study.] Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. Digitized. (1883). “Aphorismen über Staat und Kirche.” [“Aphorisms on Church and State.”] In: Viertel Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie, edited by Richard Avenarius, pp. 1–16, Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland). Digitized. (1883). “Zur Frauenfrage.” [“On the Women Question.”] In: Deutsche Zeit- und Streitfragen. Jahrgang, edited by Franz von Holzendorff, vol. 12. no. 184. pp. 297–332, Berlin: Carl Habel. Digitized. (1883). “Lambert, Johann Heinrich.” In Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, 1st ed., 17:552–56. Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 1875–1912. München/Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot. Digitized. (1884). “Über teleologischen Kriticismus.” [“On Teleological Criticism.”] In: Viertel Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie, edited by Richard Avenarius, pp. 1–17, Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland). Digitized. (1884). “Neuere Untersuchungen über Protagoras.” [“Recent Investigations into Protagoras”] In: Viertel Vierteljahrsschrift für wissenschaftliche Philosophie, edited by Richard Avenarius, pp. 479–497, Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland). Digitized. (1884). Idealismus und Positivismus. Dritter Teil: Idealistische und positivistische Erkenntnistheorie. [Idealism and Positivism. Part Three: Idealist and Positivist Epistemology.] vol. 3, Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1884. Digitized. (1884). “Einige Bemerkungen zur Transcendentalphilosophie.” [“Some Remarks on Transcendental Philosophy.”] In: Strassburger Abhandlungen zur Philosophie. Eduard Zeller zu seinem siebenzigsten Geburtstage, edited by Paul Siebeck, 61–84, Freiburg and Tübingen: Akademische Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1884. Digitized 1 and 2. (1887) Literarischer Nachlass. [Unpublished Literary Remains] Edited by Benno Kerry, Vienna: Deutschen Worte, 1887. Digitized.