|

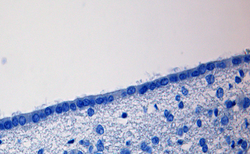

Ependyma

The ependyma is the thin neuroepithelial (simple columnar ciliated epithelium) lining of the ventricular system of the brain and the central canal of the spinal cord.[1] The ependyma is one of the four types of neuroglia in the central nervous system (CNS). It is involved in the production of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and is shown to serve as a reservoir for neuroregeneration. StructureThe ependyma is made up of ependymal cells called ependymocytes, a type of glial cell. These cells line the ventricles in the brain and the central canal of the spinal cord, which become filled with cerebrospinal fluid. These are nervous tissue cells with simple columnar shape, much like that of some mucosal epithelial cells.[2] Early monociliated ependymal cells are differentiated to multiciliated ependymal cells for their function in circulating cerebrospinal fluid.[3] The basal membranes of these cells are characterized by tentacle-like extensions that attach to astrocytes. The apical side is covered in cilia and microvilli.[4] FunctionCerebrospinal fluidLining the CSF-filled ventricles, and spinal canal, the ependymal cells play an important role in the production and regulation of CSF. Their apical surfaces are covered in a layer of cilia, which circulate CSF around the CNS.[4] Their apical surfaces are also covered with microvilli, which absorb CSF. Within the ventricles of the brain, a population of modified ependymal cells and capillaries together known as the tela choroidea form a structure called the choroid plexus, which produces the CSF.[5] Modified tight junctions between epithelial cells control fluid release. This release allows free exchange between CSF and nervous tissue of brain and spinal cord. This is why sampling of CSF, such as through a spinal tap, provides information about the whole CNS. NeuroregenerationJonas Frisén and his colleagues at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm provided evidence that ependymal cells act as reservoir cells in the forebrain, which can be activated after stroke and as in vivo and in vitro stem cells in the spinal cord. However, these cells did not self-renew and were subsequently depleted as they generated new neurons, thus failing to satisfy the requirement for stem cells.[6][7] One study observed that ependymal cells from the lining of the lateral ventricle might be a source for cells which can be transplanted into the cochlea to reverse hearing loss.[8] Clinical significanceEpendymoma is a tumor of the ependymal cells most commonly found in the fourth ventricle. See alsoReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Ependyma. |

||||||||||||||||||