|

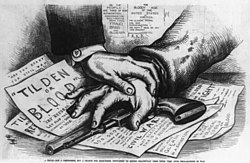

Corrupt bargainThree events in American political history have been called[citation needed] a corrupt bargain: the 1824 United States presidential election, the Compromise of 1877, and Gerald Ford's 1974 pardon of Richard Nixon. In all cases, Congress or the President acted against the most clearly defined legal course of action at the time, although in no case were the actions illegal. Two cases involved the resolution of indeterminate or disputed electoral votes from the United States presidential election process, and the third involved the controversial use of a presidential pardon. In all three cases, the president so elevated served a single term, or singular vacancy, and either did not run again or was not reelected when he ran. In the 1824 election, without an absolute majority winner in the Electoral College, the 12th Amendment dictated that the outcome of the presidential election be determined by the House of Representatives. Then Speaker of the House — and low-ranked presidential candidate in that same election — Henry Clay gave his support to John Quincy Adams, the candidate with the second-most votes. Adams was granted the presidency, and then proceeded to select Clay to be his Secretary of State. In the 1876 election, accusations of corruption stemmed from officials involved in counting the necessary and hotly contested electoral votes of both sides, in which Rutherford B. Hayes was elected by a congressional commission. Ford, who had been appointed by Nixon, became president when Nixon resigned, and gave Nixon clemency. Election of 1824  After the votes were counted in the U.S. presidential election of 1824, no candidate had received the majority needed of the presidential electoral votes (although Andrew Jackson had the most[1]), thereby putting the outcome in the hands of the House of Representatives. There were four candidates on the ballot: John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, and William H. Crawford. Following the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, however, only the top three candidates in the electoral vote were admitted as candidates, eliminating Henry Clay. To the surprise of many, the House elected John Quincy Adams over rival Andrew Jackson. It was widely believed that Clay, the Speaker of the House, convinced Congress to elect Adams, who then made Clay his Secretary of State. Jackson's supporters denounced this as a "corrupt bargain".[2][3] The "corrupt bargain" that placed Adams in the White House and Clay in the State Department launched a four-year campaign of revenge by the friends of Andrew Jackson. Claiming that the people had been cheated of their choice, Jacksonians attacked the Adams administration at every turn as illegitimate and tainted by aristocracy and corruption. Adams aided his own defeat by failing to rein in the pork barrel frenzy sparked by the General Survey Act. Jackson's attack on the national blueprint put forward by Adams and Clay won support from Old Republicans and market liberals, the latter of which increasingly argued that congressional involvement in internal improvements was an open invitation to special interests and political logrolling.[4] A 1998 analysis using game theory mathematics argued that contrary to the assertions of Jackson, his supporters, and countless later historians, the results of the election were consistent with sincere voting, that is, those Members of the House of Representatives who were unable to cast votes for their most-favored candidate apparently voted for their second- (or third-) most-favored candidate.[5] Regardless of the various theories concerning the matter, Adams was a one-term president; his rival, Jackson, was elected president by a large majority of the electors in the election of 1828 and then he defeated Clay for a second term in the election of 1832. Election of 1876 The presidential election of 1876 is sometimes considered to be a second "corrupt bargain".[6] Three Southern states had contested vote counts, and each sent the results of two different slates of electors. Since both candidates needed those electoral votes to win the election, Congress appointed a special Electoral Commission to settle the dispute over which slates of electors to accept. After the Compromise of 1877, the commission awarded all the disputed electoral votes to the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, and Congress voted to accept their report. Some of the points in the compromise are said to have already been the established position of Hayes from the time of his accepting the Republican nomination. Hayes's detractors labeled the alleged compromise a "Corrupt Bargain"[7] and mocked him with the nickname "Rutherfraud".[8] The most often cited item in the "compromise" was the agreement to accept Southern "home rule" by withdrawing the remaining Northern troops from Southern capitals. That would remove an important tool the federal government had used to force the South to uphold the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which were intended to protect the rights of African-Americans, particularly their right to vote. Generally, political support for maintaining the troops had dissipated during Grant's second term, and Hayes had little choice but to accept some form of "home rule". He attempted to do so, as stated in his nomination acceptance letter, by gaining promises from Southern states that they would respect the rights, and especially the voting rights, of the freedmen. On the other political side, the Democratic platform of Samuel Tilden, also promised the removal of troops, but with no mention of any attempts to guarantee the freedmen's rights. For a time, Hayes's approach had some success, but gradually Southern states moved to build new barriers to black suffrage and flourishing—barriers which would hold legally for almost an entire century. 1974 pardon of Nixon Gerald Ford's 1974 pardon of Richard Nixon was described as a "corrupt bargain" by critics of the disgraced former president.[citation needed] The critics claimed that Ford's pardon was quid pro quo for Nixon's resignation, which elevated Ford to the presidency. The most public critic was US Representative Elizabeth Holtzman, who, as the lowest-ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, was the only representative who explicitly asked whether the pardon was a quid pro quo. Ford cut Holtzman off, declaring, "There was no deal, period, under no circumstances."[9] See alsoReferences

|