|

Compressed tea

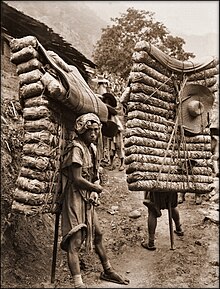

Compressed tea, called tea bricks, tea cakes or tea lumps, and tea nuggets according to the shape and size, are blocks of whole or finely ground black tea, green tea, or post-fermented tea leaves that have been packed in molds and pressed into block form. This was the most commonly produced and used form of tea in ancient China prior to the Ming Dynasty. Although tea bricks are less commonly produced in modern times, many post-fermented teas, such as pu-erh, are still commonly found in bricks, discs, and other pressed forms. Tea bricks can be made into beverages like tea or eaten as food, and were also used in the past as a form of currency. Production  In ancient China, compressed teas were usually made with thoroughly dried and ground tea leaves that were pressed into various bricks or other shapes, although partially dried and whole leaves were also used. Some tea bricks were also mixed with binding agents such as flour, blood, or manure to better preserve their form so they could withstand physical use as currency.[1] Newly formed tea bricks were then left to cure, dry, and age prior to being sold or traded. Tea bricks were preferred in Asian trade prior to the 19th century, since they were more compact and less susceptible to physical damage than loose leaf tea. This was important during transportation over land by caravans on the Tea Horse Road. Tea bricks are still currently manufactured for drinking, as in pu-erh teas, as well as for souvenirs and novelty items, though most compressed teas produced in modern times are usually made from whole leaves. The compressed tea can take various traditional forms, many of them still being produced. A dome-shaped nugget of 100g (standard size) is simply called tuóchá (沱茶), which is translated several ways, sometimes as "bird's nest tea" or "bowl tea". A small dome-shaped nugget with a dimple underneath just enough to make one pot or cup of tea is called a xiǎo tuóchá (小沱茶; the first word meaning "small") which usually weighs 3g–5g. A larger piece around 357g, which may be a disc with a dimple, is called bǐngchá (饼茶, literally "biscuit tea" or "cake tea"). A large, flat, square brick is called fāngchá (方茶, literally "square tea"). To produce a tea brick, ground or whole tea is first steamed, then placed into one of a number of types of press and compressed into a solid form. Such presses may leave an intended imprint on the tea, such as an artistic design or simply the pattern of the cloth with which the tea was pressed. Many powdered tea bricks are moistened with rice water in pressing to assure that the tea powder sticks together. The pressed blocks of tea are then left to dry in storage until a suitable degree of moisture has evaporated.

Consumption Due to their density and toughness tea bricks were consumed after they were broken into small pieces and boiled. Traditionally, in the Tang Dynasty, they were consumed being ground to a fine powder. The legacy of using tea bricks in powdered form can be seen in modern Japanese matcha tea powders as well as the pulverized tea leaves used in the lei cha (擂茶) eaten by the Hakka people and some people in Hunan province. BeverageIn ancient China the use of tea bricks involved three separate steps:

In modern times bricks of pu-erh type teas are flaked, chipped, or broken and directly steeped after thorough rinsing; the process of toasting, grinding, and whisking to make tea from tea bricks has become uncommon. Tteokcha (떡차; lit. "cake tea"), also called byeongcha (병차; 餠茶; lit. "cake tea"), was the most commonly produced and consumed type of tea in pre-modern Korea.[4][5][6] Pressed tea made into the shape of yeopjeon, the coins with holes, was called doncha (돈차; lit. "money tea"), jeoncha (전차; 錢茶; lit. "money tea"), or cheongtaejeon (청태전; 靑苔錢; lit. "green moss coin").[7][8][9] Borim-cha (보림차; 寶林茶) or Borim-baengmo-cha (보림백모차; 寶林白茅茶), named after its birthplace, the Borim temple in Jangheung, South Jeolla Province, is a popular tteokcha variety.[10] FoodTea bricks are used as a form of food in parts of Central Asia and Tibet in the past as much as in modern times. In Tibet pieces of tea are broken from tea bricks, and boiled overnight in water, sometimes with salt. The resulting concentrated tea infusion is then mixed with butter, cream or milk and a little salt to make butter tea, a staple of Tibetan cuisine.[1] The tea mixed with tsampa is called Pah. Individual portions of the mixture are kneaded in a small bowl, formed into balls and eaten. Some cities of the Fukui prefecture in Japan have food similar to tsampa, where concentrated tea is mixed with grain flour. However, the tea may or may not be made of tea bricks. In parts of Mongolia and central Asia, a mixture of ground tea bricks, grain flours and boiling water is eaten directly. It has been suggested[by whom?] that tea eaten whole provides needed roughage normally lacking in the diet. Use as currency Due to the high value of tea in many parts of Asia, tea bricks were used as a form of currency throughout China, Tibet, Mongolia, and Central Asia. This is quite similar to the use of salt bricks as currency in parts of Africa. Tea bricks were in fact the preferred form of currency over metallic coins for the nomads of Mongolia and Siberia. The tea could not only be used as money and eaten as food in times of hunger but also brewed as allegedly beneficial medicine for treating coughs and colds. Until World War II, tea bricks were still used as a form of edible currency in Siberia.[1] Tea bricks for Tibet were mainly produced in the area of Ya'an (formerly Yachou-fu) in Sichuan province. The bricks were produced in five different qualities and valued accordingly. The kind of brick which was most commonly used as currency in the late 19th and early 20th century was that of the third quality which the Tibetans called "brgyad pa" ("eighth"), because at one time it was worth eight Tibetan tangkas (standard silver coin of Tibet which weighs about 5.4 grams) in Lhasa. Bricks of this standard were also exported by Tibet to Bhutan and Ladakh.[11] Health effectsAll tea plant tissues accumulate fluorine to some extent. Tea bricks that are made from old tea leaves and stems can accumulate large amounts of this element, which can make them unsafe for consumption in large quantities or over prolonged periods. Use of such teas has led to fluorosis, a form of fluoride poisoning that affects the bones and teeth, in areas of high brick tea consumption such as Tibet.[12] ReferencesCitations

Sources

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||