|

Bristol Bridge

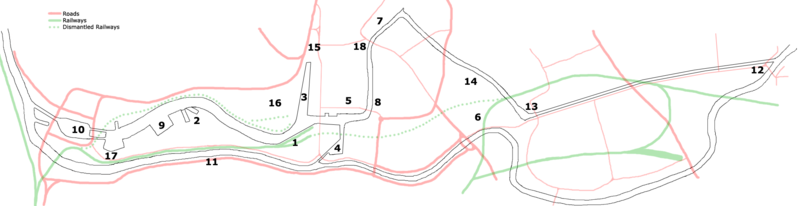

Bristol Bridge is a bridge over the floating harbour in Bristol, England. The floating harbour was constructed on the original course of the River Avon, and there has been a bridge on the site since long before the harbour was created by impounding the river in 1809. The current bridge was completed in 1768 and is a Grade II listed building.[1] Bristol Bridge is the furthest downstream of the fixed bridges across the harbour, and marks the limit of navigation for any vessel that is unable to pass beneath its arches. Downstream from the bridge the harbour is lined by wharves and warehouses, with Welsh Back to the west and Redcliffe Back to the east. Upstream, the land to the west is occupied by Castle Park, created on an area destroyed by bombing during the Second World War, whilst the opposite bank is occupied by the former Georges Bristol Brewery, now redeveloped as Finzels Reach.[2] HistoryBristol's name is derived from the Saxon Brycgstow or 'Brigstowe', meaning the 'place of the bridge'.[3] However, it is unclear when the first bridge over the Avon was built. The Avon has a high tidal range, so the river could have been forded twice a day. The name may therefore refer to the many smaller bridges over the Avon's tributary, the River Frome, constructed in the marshy surrounding area, which is now largely built over. The first stone bridge was built in 1247, and houses with shopfronts were built on it.[4][5] A 17th-century illustration shows that these bridge houses were five stories high, including the attic rooms, and that they overhung the river much as Tudor houses would overhang the street.[6] The bridge was regarded as a place where the wealthy would live, hosting a community of goldsmiths.[5] Houses on the bridge were attractive and charged high rents as they had so much passing traffic, and had plenty of fresh air while waste could be dropped into the river.[6] Its population was also perceived to be strongly parliamentarian.[6] During the Civil War in 1647, the bridge was struck by fire, with 24 houses being burnt.[5]  In 1760 a bill to replace the bridge was carried through parliament by the Bristol MP Sir Jarrit Smyth.[7] By the early 18th century, increase in traffic and the encroachment of shops on the roadway made the bridge fatally dangerous for many pedestrians, but despite a campaign by Felix Farley in his Journal, no action was taken until a shopkeeper on the bridge employed James Bridges to provide designs. The commission accepted the design of James Bridges after many long drawn out disputes which are still unclear. Bridges fled to the West Indies in 1763 leaving Thomas Paty to complete it between 1763 and 1768. The bridge that was completed by 1768 largely resembles the present structure.[5] Resentment at the tolls exacted to cross the new bridge occasioned the Bristol Bridge Riot of 1793. The toll houses were turned into shops before they were removed. In the 19th century, the roadway was again congested, so walkways were added on either side, the supporting columns disguising the classical Georgian design. The current metal railings date from the 1960s. Before the Second World War, Bristol Bridge was an important transport hub. It was the terminus of tram routes to Knowle, Bedminster and Ashton Gate, and other trams also stopped here.[8] It lost importance when Temple Way was built further upstream in the 1930s,[9] and when the tram system closed in 1941. Bristol Bridge was closed to private motor cars and goods vehicles under 7.5 tonnes in 2020 as part of Bristol City Council's initiative to improve air quality, accelerated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[10]

See alsoReferences

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||