|

Brahmana

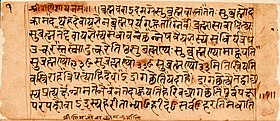

The Brahmanas (/ˈbrɑːmənəz/; Sanskrit: ब्राह्मणम्, IAST: Brāhmaṇam) are Vedic śruti works attached to the Samhitas (hymns and mantras) of the Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva Vedas. They are a secondary layer or classification of Sanskrit texts embedded within each Veda, which explain and instruct on the performance of Vedic rituals (in which the related Samhitas are recited). In addition to explaining the symbolism and meaning of the Samhitas, Brahmana literature also expounds scientific knowledge of the Vedic Period, including observational astronomy and, particularly in relation to altar construction, geometry. Divergent in nature, some Brahmanas also contain mystical and philosophical material that constitutes Aranyakas and Upanishads.[1] Each Veda has one or more of its own Brahmanas, and each Brahmana is generally associated with a particular Shakha or Vedic school. Less than twenty Brahmanas are currently extant, as most have been lost or destroyed. Dating of the final codification of the Brahmanas and associated Vedic texts is controversial, as they were likely recorded after several centuries of oral transmission.[2] The oldest Brahmana is dated to about 900 BCE, while the most recent are dated to around 700 BCE.[3][4] Nomenclature and etymologyBrahmana (or Brāhmaṇam, Sanskrit: ब्राह्मणम्) can be loosely translated as 'explanations of sacred knowledge or doctrine' or 'Brahmanical explanation'.[5] According to the Monier-Williams Sanskrit dictionary, 'Brahmana' means:[6]

EtymologyM. Haug states that etymologically, 'the word ['Brahmana' or 'Brahmanam'] is derived from brahman which properly signifies the Brahma priest who must know all Vedas, and understand the whole course and meaning of the sacrifice... the dictum of such a Brahma priest who passed as a great authority, was called a Brahmanam'.[7] SynonymsS. Shrava states that synonyms of the word 'Brahmana' include:[8]

Overview R. Dalal states that the 'Brahmanas are texts attached to the Samhitas [hymns] – Rig, Sama, Yajur and Atharva Vedas – and provide explanations of these and guidance for the priests in sacrificial rituals'.[13] S. Shri elaborates, stating 'Brahmanas explain the hymns of the Samhitas and are in both prose and verse form... The Brahmanas are divided into Vidhi and Arthavada. Vidhi are commands in the performance of Vedic sacrifices, and Arthavada praises the rituals, the glory of the Devas and so on. The belief in reincarnation and transmigration of soul started with [the] Brahmanas... [The] Brahmana period ends around 500 BC[E] with the emergence of Buddhism and it overlaps the period of Aranyakas, Sutras, Smritis and the first Upanishads'.[14] M. Haug states that the 'Veda, or scripture of the Brahmans, consists, according to the opinion of the most eminent divines of Hindustan, of two principal parts, viz. Mantra [Samhita] and Brahmanam... Each of the four Vedas (Rik, Yajus, Saman, and Atharvan) has a Mantra, as well as a Brahmana portion. The difference between both may be briefly stated as follows: That part which contains the sacred prayers, the invocations of the different deities, the sacred verses for chanting at the sacrifices, the sacrificial formulas [is] called Mantra... The Brahmanam [part] always presupposes the Mantra; for without the latter it would have no meaning... [they contain] speculations on the meaning of the mantras, gives precepts for their application, relates stories of their origin... and explains the secret meaning of the latter'.[7] J. Eggeling states that 'While the Brâhmanas are thus our oldest sources from which a comprehensive view of the sacrificial ceremonial can be obtained, they also throw a great deal of light on the earliest metaphysical and linguistic speculations of the Hindus. Another, even more interesting feature of these works, consists in the numerous legends scattered through them. From the archaic style in which these mythological tales are generally composed, as well as from the fact that not a few of them are found in Brâhmanas of different schools and Vedas, though often with considerable variations, it is pretty evident that the ground-work of many of them goes back to times preceding the composition of the Brâhmanas'.[15] The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) states that while 'the Upanishads speculate on the nature of the universe, and the relationship of the one and the many, the immanent and transcendental, the Brahmanas make concrete the world-view and the concepts through a highly developed system of ritual-yajna. This functions as a strategy for a continuous reminder of the inter-relatedness of man and nature, the five elements and the sources of energy'.[16] Performance of ritualsThe Brahmanas are particularly noted for their instructions on the proper performance of rituals, as well as explanations on the symbolic importance of sacred words and ritual actions.[17] Academics such as P. Alper, K. Klostermaier and F.M, Muller state that these instructions insist on exact pronunciation (accent),[18] chhandas (छन्दः, meters), precise pitch, with coordinated movement of hand and fingers – that is, perfect delivery.[19][20] Klostermaier adds that the Satapatha Brahamana, for example, states that verbal perfection made a mantra infallible, while one mistake made it powerless.[19] Scholars suggest that this orthological perfection preserved Vedas in an age when writing technology was not in vogue, and the voluminous collection of Vedic knowledge were taught to and memorized by dedicated students through Svādhyāya, then remembered and verbally transmitted from one generation to the next.[19][21] It seems breaking silence too early in at least one ritual is permissible in the Satapatha (1.1.4.9), where 'in that case mutter some Rik [Rigveda] or Yagus-text [Yajurveda] addressed to Vishnu; for Vishnu is the sacrifice, so that he thereby regains obtains a hold on the sacrifice, and penance is there by done by him'.[22] The NiruktaRecorded by the grammarian Yaska, the Nirukta, one of the six Vedangas or 'limbs of the Vedas' concerned with correct etymology and interpretation of the Vedas, references several Brahmanas to do so. These are (grouped by Veda):[23]

Commentaries of SayanaThe 14th Century Sanskrit scholar Sayana composed numerous commentaries on Vedic literature, including the Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads. B.R. Modak states that 'king Bukka [1356–1377 CE] requested his preceptor and minister Madhavacharya to write a commentary on the Vedas, so that even common people would be able to understand the meaning of the Vedic Mantras. Madhavacharya told him that his younger brother Sayana was a learned person and hence he should be entrusted with the task'.[24] Modak also lists the Brahmanas commented upon by Sayana (with the exception of the Gopatha):[24]

Abbreviations and schoolsFor ease of reference, academics often use common abbreviations to refer to particular Brahmanas and other Vedic, post-Vedic (e.g. Puranas), and Sanskrit literature. Additionally, particular Brahmanas linked to particular Vedas are also linked to (i.e. recorded by) particular Shakhas or schools of those Vedas as well. Based on the abbreviations and Shakhas provided by works cited in this article (and other texts by Bloomfield, Keith, W. D, Whitney, and H.W. Tull),[25][26][27][28] extant Brahmanas have been listed below, grouped by Veda and Shakha. Note that:

Recensions by Disciples of VyasaS. Sharva states that in 'the brahmana literature this word ['brahmana'] has been commonly used as detailing the ritualism related to the different sacrifices or yajnas... The known recensions [i.e. schools or Shakhas] of the Vedas, all had separate brahmanas. Most of these brahmanas are not extant.... [Panini] differentiates between the old and the new brahmanas... [he asked] Was it when Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa had propounded the Vedic recensions? The brahmanas which had been propounded prior to the exposition of recensions by [Vyasa] were called as old brahmanas and those which had been expounded by his disciples were known as new brahmanas'.[8] RigvedaThe Aitareya, Kausitaki, and Samkhyana Brahmanas are the two (or three) known extant Brahmanas of the Rigveda. A.B. Keith, a translator of the Aitareya and Kausitaki Brahmanas, states that it is 'almost certainly the case that these two [Kausitaki and Samkhyana] Brahmanas represent for us the development of a single tradition, and that there must have been a time when there existed a single... text [from which they were developed and diverged]'.[33] Although S. Shrava considers the Kausitaki and Samkhyana Brahmanas to be separate although very similar works,[8] M. Haug considers them to be the same work referred to by different names.[7] Aitareya Brahmana

As detailed in the main article, the Aitareya Brahmana (AB) is ascribed to the sage Mahidasa Aitareya of the Shakala Shakha (Shakala school) of the Rigveda, and is estimated to have been recorded around 600-400 BCE.[33] It is also linked with the Ashvalayana Shakha.[13] The text itself consists of eight pañcikās (books), each containing five adhyayas (chapters), totaling forty in all. C. Majumdar states that 'it deals principally with the great Soma sacrifices and the different ceremonies of royal inauguration'.[29] Haug states that the legend about this Brahmana, as told by Sayana, is that the 'name "Aitareya" is by Indian tradition traced to Itara... An ancient Risi had among his many wives one who was called Itara. She had a son Mahidasa by name [i.e. Mahidasa Aitareya]... The Risi preferred the sons of his other wives to Mahidasa, and went even so far as to insult him once by placing all his other children in his lap to his exclusion. His mother, grieved at this ill-treatment of her son, prayed to her family deity (Kuladevata), [and] the Earth (Bhumi), who appeared in her celestial form in the midst of the assembly, placed him on a throne (simhasana), and gave him as a token of honour for his surpassing all other children in learning a boon (vara) which had the appearance of a Brahmana [i.e. the Aitareya]'.[7] P. Deussen agrees, relating the same story.[35] Notably, The story itself is remarkably similar to the legend of a Vaishnava boy called Dhruva in the Puranas (e.g. Bhagavata Purana, Canto 4, Chapter 8-12).[36] Kausitaki / Samkhyana Brahmana

The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) states that the 'Kaushitaki Brahmana [is] associated with Baskala Shakha of [the] Rigveda and [is] also called Sankhyayana Brahmana. It is divided into thirty chapters [adhyayas] and 226 Khanda[s]. The first six chapters dealing with food sacrifice and the remaining to Soma sacrifice. This work is ascribed to Sankhyayana or Kaushitaki'.[37] S. Shrava disagrees, stating that it 'was once considered that [the] Kaushitaki or Samkhayana was the name of the same brahmana... [but the Samkhayana] differs, though slightly, from the Kaushitaki Brahmana'.[8] C. Majumdar states that it 'deals not only with the Soma, but also other sacrifices'.[29] Keith estimates that the Kaushîtaki-brâhmana was recorded around 600–400 BCE, adding that it is more 'scientific' and 'logical' than the Aitareya Brahmana, although much 'of the material of the Kausitaki, and especially the legends, has been taken over by the Brahmana from a source common to it and the Aitareya, but the whole has been worked up into a harmonious unity which presents no such irregularities as are found in the Aitareya. It is clearly a redaction of the tradition of the school made deliberately after the redaction of the Aitareya'.[33] Kaushitaki Brahmana UpanishadMax Müller states that the Kaushitaki Upanishad – also called the Kaushitaki Brahmana Upanishad (KBU) – 'does not form part of the Kaushîtaki-brâhmana in 30 adhyâyas which we possess, and we must therefore account for its name by admitting that the Âranyaka, of which it formed a portion, could be reckoned as part of the Brâhmana literature of the Rig-veda (see Aitareya-âranyaka, Introduction, p. xcii), and that hence the Upanishad might be called the Upanishad of the Brâhmana of the Kaushîtakins'.[38] SamavedaW. Caland states that of the Samaveda, three Shakhas (schools or branches) 'are to be distinguished; that of the Kauthumas, that of the Ranayaniyas, and that of the Jaiminiyas'.[39] Panchavimsha / Tandya Brahmana

Caland states that the Panchavimsha / Tandya Brahmana of the Kauthuma Shakha consists of 25 prapathakas (books or chapters).[39] C. Majumdar states that it 'is one of the oldest and most important of Brahmanas. It contains many old legends, and includes the Vratyastoma, a ceremony by which people of non-Aryan stock could be admitted into the Aryan family'.[29] Sadvimsa Brahmana The Sadvimsa Brahmana is also of the Kauthuma Shakha, and consists of 5 adhyayas (lessons or chapters). Caland states it is 'a kind of appendix to the [Panchavimsha Brahmana], reckoned as its 26th book [or chapter]... The text clearly intends to supplement the Pancavimsabrahmana, hence its desultory character. It treats of the Subrahmanya formula, of the one-day-rites that are destined to injure (abhicara) and other matters. This brahmana, at least partly, is presupposed by the Arseyakalpa and the Sutrakaras'.[39] Adbhuta BrahmanaCaland states that the Adbhuta Brahmana, also of the Kauthuma Shakha, is the 'latest part [i.e. 5th adhyaya of the Sadvimsa Brahmana], that which treats of Omina and Portenta [Omens and Divination]'.[39] Majumdar agrees.[29] Samavidhana BrahmanaCaland states that the Samavidhana Brahmana of the Kauthuma Shakha is 'in 3 prapathakas [books or chapters]... its aim is to explain how by chanting various samans [hymns of the Samaveda][41] some end may be attained. It is probably older than one of the oldest dharmasastras, that of Gautama'.[39] M. S. Bhat states that it is not properly a Brāhmaṇa text, but belongs to the Vidhāna literature.[42] Daivata Brahmana Caland states that the Daivata Brahmana of the Kauthuma Shakha is 'in 3 prapathakas [books or chapters]... It deals with the deities to which the samans are addressed'.[39] Dalal adds that the 'first part of the Devatadhyaya is the most important as it provides rules to determine the deities to whom the samans are dedicated. Another section ascribes colours to different verses, probably as aids to memory or for meditation... [It] includes some very late passages such as references to the four yugas or ages'.[13] Samhitopanishad BrahmanaCaland states that the Samhitopanishad Brahmana of the Kauthuma Shakha is 'in 5 khandas [books]... It treats of the effects of recitation, the relation of the saman [hymns of the Samaveda] and the words on which it is chanted, the daksinas to be given to the religious teacher'.[39] Dalal agrees, stating that it 'describes the nature of the chants and their effects, and how the riks or Rig Vedic verses were converted into samans. Thus it reveals some of the hidden aspects of the Sama Veda'.[13] Arsheya BrahmanaCaland states that the Arsheya Brahmana of the Kauthuma Shakha is ''in 3 prapathakas [books or chapters]... This quasi-brahmana is, on the whole, nothing more than an anukramanika, a mere list of the names of the samans [hymns of the Samaveda] occurring in the first two ganas [of the Kauthumas, i.e. the Gramegeya-gana / Veya-gana and the Aramyegeya-gana / Aranya-gana]'.[39] The nature of the ganas noted are discussed in the same text. As illustrated below, this Brahmana is virtually identical to the Jaiminiya Arsheya Brahmana of the Jaiminiya Shakha. Vamsha BrahmanaCaland states that the Vamsha Brahmana of the Kauthuma Shakha is 'in 3 khandas [books]... it contains the lists of teachers of the Samaveda'.[39] Notably, Dalal adds that of the 53 teachers listed, the 'earliest teacher, Kashyapa, is said to have received the teaching from the god, Agni'.[13] Jaiminiya Brahmana

It seems that this Brahmana has not been fully translated to date, or at least a full translation has not been made available. S. Shrava states that the Jaiminiya Brahmana of the Jaiminiya Shakha, also called the Talavakara Brahmana, 'is divided into 1348 khandas [verses]... Many of the sentences of this brahmana are similar to those found in Tamdya, Sadavimsam, Satapatha [Brahmanas] and [the] Taittirya Samhita [Krishna/Black Yajurveda]. Many of the hymns are found for the first time in it. Their composition is different from that available in Vedic literature. Most of the subjects described in it are completely new and are not found in other bramanas like Tamdya, etc... In the beginning khandas, details of daily oblation to the sacrificial fire are described... This brahmana was compiled by Jaimini a famous preceptor of Samaveda and the worthy disciple of Krishna Dvaipayana Vedavyasa and his disciple Talavakara'.[8] Jaiminiya Arsheya BrahmanaDalal states that the Jaiminiya Arsheya Brahmana of the Jaiminiya Shakha 'is similar to the Arsheya Brahmana of the Kauthuma school but for the fact that the names of the rishis in the two are different. Unlike the Kauthuma texts, this lists only one rishi per saman'.[13] Jaiminiya Upanishad BrahmanaAs detailed in the main article, also called the Talavakara Upanishad Brahmana and Jaiminiyopanishad Brahmana, it is considered an Aranyaka – not a Brahmana – and forms part of the Kena Upanishad. Chandogya Brahmana

The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) states that the Chandogya Brahmana, also called the chanddogyopanishad Brahmana, 'is divided into ten prapathakas (chapters). Its first two prapathakas (chapters) form the Mantra Brahmana (MB) and each of them is divided into eight khandas (sections). Prapathakas 3–10 form the Chandogya Upanishad'.[47] K.G. Witz states it is of the Kauthuma Shakha (see below).[48] Mantra Brahmana

K. G. Witz states that the Mantra Brahmana is 'a text in two chapters which mostly give Vedic Mantras which should be used in rites such as for birth and marriage. The combined text [with 8 chapters forming the Chandogya Upanishad] is [also] called [the] Upanishad Brahmana and is one of the eight canonical Brahmanas of the Kauthumas. The fact that the Upanishad was combined with the Mantra Brahmana into a single text is significant. Just as everyone in society is blessed and made part of the overall divine societal, social and world order by the household rites in the Mantra Brahmana, so everyone can direct his life toward the Infinite Reality by the numerous upasanas and vidyas of the Chandogya Upanishad.'[48] R. Mitra is quoted as stating that of 'the two portions differ greatly, and judged by them they appear to be productions of very different ages, though both are evidently relics of pretty remote antiquity. Of the two chapters of the Khandogya-Brahmana [Chandogya Brahmana, forming the Mantra Brahmana], the first includes eight suktas [hymns] on the ceremony of marriage and the rites necessary to be observed at the birth of a child. The first Sukta is intended to be recited when offering an oblation to Agni on the occasion of a marriage, and its object is to pray for prosperity [on] behalf of the married couple. The second prays for a long life, kind relatives, and a numerous progeny [i.e. children]. The third is the marriage pledge by which the [couple] bind themselves to each other. Its spirit may be guessed from a single verse. In talking of the unanimity with which they will dwell, the bridegroom addresses his bride, "That heart of thine shall be mine, and this heart of mine shall be thine" [as quoted above]'.[50] YajurvedaŚukla (White) Yajurveda: Shatapatha Brahmana

The 'final form' of the Satapatha Brahmana is estimated to have been recorded around 1000–800 BCE, although it refers to astronomical phenomena dated to 2100 BCE, and, as quoted above, historical events such as the drying up of the Sarasvati river, which is believed to have occurred around 1900 BCE.[53] It provides scientific knowledge of geometry and observational astronomy from the Vedic period, and is considered significant in the development of Vaishnavism as the possible origin of several Puranic legends and avatars of the RigVedic god Vishnu, all of which (Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, and Vamana) are listed in the Dashavatara. M. Winternitz states that this Brahmana is 'the best known, the most extensive, and doubtless, also on account of its contents, the most important of all the Brahmanas'.[1] Eggeling states that 'The Brâhmana of the Vâgasaneyins bears the name of Satapatha, that is, the Brâhmana 'of a hundred paths,' because it consists of a hundred lectures (adhyâyas). Both the Vâgasaneyi-samhitâ [Yajurveda] and the Satapatha-brâhmana have come down to us in two different recensions, those of the Mâdhyandina and the Kânva schools':[15]

Krishna (Black) Yajurveda: Taittiriya Brahmana

Ascribed to the sage Tittiri (or Taittiri), the Taittiriya Brahmana of the Taittiriya Shakha consists of three Ashtakas (books or parts) of commentaries on the performance of Vedic sacrificial rituals, astronomy, and information about the gods. It is stated by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) to be 'mixed of mantras and Brahmans... composed in poetic and prose manner'.[55] M. Winternitz adds that the "Taittiriya-Brahmana of the Black Yajurveda is nothing but a continuation of the Taittiriya-Samhita, for the Brahmanas were already included in the Samhitas of the Black Yajurveda. The Taittiriya-Brahmana, therefore, contains only later additions to the Samhita."[1] According to the Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary, Taittiri was a disciple of Yaska (300–400 BCE),[56] although according to the Vishnu Purana (Book 3, Chapter 5), Taittiri and Yaska were disciples of Vaiśampáyana (500–600 BCE).[57] According to H.H. Wilson, in the Anukramańí (index of the black Yajurveda), it 'is there said that Vaiśampáyana taught it to Yaska, who taught it to Tittiri, who also became a teacher; whence the term Taittiríya, for a grammatical rule explains it to mean, 'The Taittiríyas are those who read what was said or repeated by Tittiri'.'[58] Taittiriya ChardiAlthough the Taittiriya Chardi Brahmana is mentioned (i.e. listed) by academics such as S. Shri[14] and S.N. Nair,[59] no further information could be found. Taittiriya PravargyaThe Taittiriya Pravargya is a commentary on the Pravargya ritual, contained in the Taittiriya Aranyaka. This is not listed or referred to as a Brahmana in the works cited. Vadhula – AnvakhyanaDalal states that the Vadhula (or Anvakhyana) Brahmana of the Vadhula Shakha is 'a Brahmana type of text, though it is actually part of the Vadhula Shrauta Sutra'.[13] However, B.B. Chaubey states that about 'the nature of the text there has been confusion whether VadhAnva [Vadhula Anvakhyana Brahmana] is a Brahmana, or an Anubrahmana ['work resembling a brahmana' or 'according to the brahmana'],[60] or an Anvakhyana ['explanation keeping close to the text' or 'minute account or statement'].[61] When Caland found some newly discovered MSS [manuscript] of the Vadhula School he was not sure about the nature of the text. Because of the composite nature of the MS [manuscript] he took the text as part of the Srautasurta of the Vadhulas. However, he was not unaware of the Brahmanic character of the text... according to Caland, the word Anvakhyana was given as a specific name to the Brahmanas, or Brahmana-like passages of the Vadhulasutra'.[62] Atharvaveda According to M. Bloomfield, the 9 shakhas – schools or branches – of the Atharvaveda are:[63]

Gopatha Brahmana

Bloomfield states that the Gopatha Brahmana 'does not favour us with a report of the name of its author or authors. it is divided into two parts, the purva-brahmana in five prapathakas (chapters), and the uttara-brahmana in six prapathakas. The purva shows considerable originality, especially when it is engaged in the glorification of the Atharvan and its priests; this is indeed its main purpose. Its materials are by no means all of the usual Brahmana-character; they broach frequently upon the domain of Upanishad... The uttara has certainly some, though probably very few original sections'.[63] S.S. Bahulkar states that the 'Gopatha Brahmana (GB.) is the only brahmana text of AV [Atharvaveda], belonging to both the recensions [Shakhas], viz. Saunaka and Paippalada'.[65] Dalal agrees, stating the 'aim of this Brahmana seems to be to incorporate the Atharva [Veda] in the Vedic ritual, and bring it in line with the other three Vedas. This Brahmana is the same for the Paippalada and Shaunaka shakhas, and is the only existing Brahmana of the Artharva Veda'.[13] C. Majumdar states that 'although classed as a Brahmana, [it] really belongs to the Vedanga literature, and is a very late work'.[29] Lost BrahmanasM Haug states that there 'must have been, as we may learn from Panini and Patanjali's Mahabhasya, a much larger number of Brahmanas belonging to each Veda; and even Sayana, who lived only about four [now five] hundred years ago, was acquainted with more than we have now'.[7] S. Shrava states that 'Innumerable manuscripts of the valuable [Vedic] literature have been lost due to atrocities of the rulers and invaders, ravages of time, and utter disregard and negligence. These factors contributed to the loss of hundreds of manuscripts. Once their number was more than a few hundred. Had these been available today the ambiguity in the interpretation of Vedic hymns could not have crept in'.[8] Based on references in other Sanskrit literature, Shrava lists many of these lost works:[8] Rigveda

Samaveda

Yajurveda

|- |Chhagaleya |A division of the Taittiriya school. Referred to in works such as the Baudhayana Srauta Sutra. |} UnknownThe Brahmanas listed below are often only mentioned by name in other texts without any further information such as what Veda they are attached to.

Manuscripts and translationsRigveda

Yajurveda

Atharvaveda

Lost Brahmanas (fragments)

See also

References

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||