|

Bank of America Tower (Manhattan)

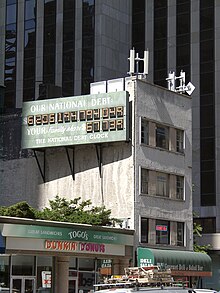

The Bank of America Tower, also known as 1 Bryant Park, is a 55-story skyscraper in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It is located at 1111 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue) between 42nd and 43rd Streets, diagonally opposite Bryant Park. The building was designed by Cookfox and Adamson Associates, and it was developed by the Durst Organization for Bank of America. With a height of 1,200 feet (370 m), the Bank of America Tower is the ninth tallest building in New York City and the tenth tallest building in the United States as of 2022[update]. The Bank of America Tower has 2.1 million square feet (200,000 m2) of office space, much of which is occupied by Bank of America. The building consists of a seven-story base that occupies the entire plot, above which rises the tower. Its facade is largely composed of a curtain wall made of insulated glass panels. The building's base incorporates the Stephen Sondheim Theatre, a New York City designated landmark, as well as several retail spaces and a pedestrian atrium. The Bank of America Tower received a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Platinum green building certification upon its opening; however, because of its high energy use, the building was exceeding citywide emissions limits by the early 2020s. Seymour Durst had acquired land on the site starting in the 1960s, with plans to develop a large building there, though he was unable to do so because of the presence of other property owners. His son Douglas Durst proposed a large office skyscraper at the beginning of the 21st century and continued to acquire land through 2003. After Bank of America was signed as an anchor tenant, work on the building started in 2004. Despite several incidents during construction, the building was completed in 2009 at a cost of $1 billion. In addition to Bank of America, the tower's tenants have included Marathon Asset Management, Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, and Roundabout Theatre Company. SiteThe Bank of America Tower is on the western side of Sixth Avenue (officially Avenue of the Americas[1]) between 42nd Street and 43rd Street, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City.[2][3] While its legal address is 1111 Avenue of the Americas,[2] it is known as 1 Bryant Park.[3][4][5] The building's Bryant Park address arose because its namesake tenant Bank of America, which wanted the tower to be easily related with Bryant Park to the southeast.[6] The government of New York City does not consider 1 Bryant Park to be a real address, as Bryant Park is not the name of a street, but Bank of America applied for 1 Bryant Park to be a "vanity address" under city planning law.[5] The land lot is rectangular and covers 87,863 sq ft (8,162.7 m2). The site has a frontage of 437.5 ft (133.4 m) on 42nd and 43rd Streets and a frontage of 200 ft (61 m) on Sixth Avenue.[2] The building is surrounded by 149 stainless-steel bollards, placed on the sidewalks at intervals of 5 feet (1.5 m).[7] The Bank of America Tower, as well as 4 Times Square to the west, comprise the entire city block. Other nearby locations include the Town Hall theater and the Lambs Club to the north, The Knickerbocker Hotel to the southwest, Bush Tower and 1095 Avenue of the Americas to the south, and Bryant Park to the southeast.[2][3] The site is directly bounded to the south and east by New York City Subway tunnels.[8] Previous buildingsHistorically, the area had been composed of hills and meadows, and a stream ran on the western boundary of the site.[9] Prior to the Bank of America Tower's construction, the site was occupied by several structures.[10][11] The neighborhood had been occupied by row houses with backyards in the late 19th century, which were demolished for commercial development in the early 20th century.[8] Many of the former structures on the site were stores, restaurants, and theaters.[11] There was a pair of two-story buildings at 1111 Avenue of the Americas and 105-109 West 42nd Street just before the tower's development.[10] A 20- or 22-story commercial building, the Remington Building, stood at 113 West 42nd Street.[8][12] The Hotel Diplomat, a 13-story structure at 108 West 43rd Street that had operated since 1911, occupied the northern part of the site.[13] The block also had a Masonic Temple,[14] as well as the eight-story Roger Baldwin Building at 132 West 43rd Street, once headquarters of the American Civil Liberties Union.[15] The northern side of the Bank of America Tower incorporates the Stephen Sondheim Theatre (originally Henry Miller's Theatre), which was rebuilt when the tower was erected.[3][4][8] Subway entrance Immediately outside the Bank of America Tower is an entrance to the New York City Subway's 42nd Street–Bryant Park/Fifth Avenue station,[4][16] which is served by the 7, <7>, B, D, F, <F>, and M trains.[17] The entrance is designed to harmonize with the lobby adjacent to it.[18] The subway entrance consists of a glass enclosure with a pair of staircases, which lead north and south from Sixth Avenue to the station's underground mezzanine.[4] The subway entrance has an elevator as well.[16] On the subway entrance's glass roof is a BIPV installation, which produces some electricity for the structure.[19] As part of the building's construction, a passageway was built under the north side of 42nd Street connecting the Bryant Park complex with the Times Square–42nd Street station.[16] However, the passageway remained closed even when the building was completed. As part of the reconstruction of 42nd Street Shuttle from 2019 to 2022, the passageway would have been opened and a new entrance would be built on the north side of 42nd Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue.[20][21] Because the Durst Organization did not want to pay for an underpass between the new shuttle platform and the Bank of America Tower's passageway, a parallel ramp between the two stations was built instead, leaving the Bank of America Tower's passageway unused.[22] ArchitectureThe Bank of America Tower was developed by Douglas Durst of the Durst Organization and designed by Cookfox Architects for Bank of America.[3][23] Adamson Associates served as the executive designer.[24][25] Severud Associates was the structural engineer, Jaros, Baum & Bolles was the MEP engineer, and Tishman Realty & Construction was the general contractor. Numerous other consultants, engineers, and contractors were involved in the building's design and construction.[23][24]  The building contains 2.1 million square feet (195,096 m2) of office space.[26] It has three basements[8][27] and has 55 above-ground stories.[28][29][30][a] The Bank of America has two spires: an architectural spire to the south, rising 1,200 feet (370 m), and a wind turbine on the north, rising 960 feet (290 m).[28] The height to the architectural spire makes the Bank of America Tower the eighth tallest building in New York City and the tenth tallest building in the United States as of 2021[update].[24][31] When only roof height is counted, the building rises to 944.5 feet (287.9 m) on the south end and 848 feet (258.5 m) on the north end.[28] The Bank of America Tower was the first commercial skyscraper in the U.S. specifically designed to attain a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Platinum certification, the highest green building certification available from LEED.[32] The Bank of America Tower was imitated worldwide as a model for sustainable architecture in skyscrapers.[33] The energy-efficiency features increased the building's construction cost by 6.5 percent, but they were projected to save $3 million a year in annual energy costs and increase productivity by another $7 million annually.[34] When the building opened, the effectiveness of the environmental features was lessened by its high occupancy rates.[35][36] As a result, the building was given a "C" grade (on an "A" through "F" scale) on a citywide energy-efficiency ranking system in 2018.[37] Another consequence was that the building risked being penalized for excessive carbon emissions under a 2019 law.[38][39] Bloomberg reported in 2022 that the building could exceed city emissions limits by an estimated 50 percent by 2024, resulting in an annual fine of $2.4 million.[40] Form and facade The building contains a seven- and eight-story base that occupies the entire plot.[8][23] The tower rises above the eastern portion of the plot, covering 32,500 square feet (3,020 m2).[9] The facade contains several diagonal planes, which are designed to reduce wind resistance compared to a rectangular massing.[41] Serge Appel of Cookfox said the tower's massing would conform with Bank of America's wish for "an iconic form"[42] and would maximize views of other buildings.[43][44] One section of the building has a roof garden covering 4,500 square feet (420 m2).[45] The building's three basement levels reach as deep as 55 feet (17 m) below grade.[9] At the lowest stories, the Bank of America Tower's floor plan resembles a rectangle, though the northeast and southwest corners protrude by about 15 feet (4.6 m).[27] The southeast corner, facing Bryant Park, is a right angle at the lowest one-third of the building.[23] However, it is a wedge-shaped chamfer on the upper two-thirds of the tower, giving each successive story a different shape.[23][27] During the planning process, the architects considered orienting the Bank of America Tower diagonally so it faced Bryant Park, but they ultimately decided to keep the base aligned with the Manhattan street grid as an "urban gesture".[44] The upper stories are aligned diagonally to the street grid because of the sloped facades on upper stories.[46] Tower facadeThe facade of the Bank of America Tower is, for the most part, composed of a glass curtain wall covering over 700 thousand square feet (65,000 m2). The curtain wall includes vertical and sloped sections at the base, as well as double walls and screen walls in the upper stories.[47] The glass panels at the base are set between horizontal and vertical mullions.[41] Each story has full-height panels with insulated glazing.[47][48] The tops and bottoms of each panel are composed of fritted glass, but the middle of the panel is transparent to allow views of the surroundings.[19] In total, 8,644 panels are used in the curtain wall.[49] On upper stories, the mullions between windows appear to be vertical, but they run in a slight diagonal to accommodate the sloped facades.[27] The curtain wall was partially inspired by the New York Crystal Palace, a 19th-century exhibition building that occupied what is now Bryant Park.[44][48][50] Inspiration was also derived from the Durst family's collection of crystals.[44] According to Richard Cook of Cookfox, the curtain wall was meant to express the idea that "the ideal of modern banking is open, clear, transparent".[51]  The Bank of America Tower's curtain wall was specifically designed to meet LEED standards, allowing natural light into the lobby and offices during the daytime.[32] Above the main entrance on 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue is an installation of building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs), which produce small amounts of energy for the building.[52] Some spandrels on the eastern facade also contain BIPVs.[19] The southeast-corner chamfer is designed with a double-glazed wall,[52] which deflects sunlight during the summer.[47][48] The double-insulated curtain wall panels cover 20,825 square feet (1,934.7 m2). The curtain wall allows 73 percent of visible light to enter but deflects all ultraviolet rays. The curtain wall design keeps heat out of the building during summer and keeps heat inside during winter.[53] Above the main entrance, there is an oxidized-bamboo canopy.[42][54] Extending 25 feet (7.6 m) outward from the lobby, the entrance canopy continues indoors as the ceiling of the lobby.[54] Stephen Sondheim TheatreThe facade of Henry Miller's Theatre (now the Stephen Sondheim Theatre) is protected by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission as an official city landmark. It is preserved on 124 West 43rd Street at the base of the Bank of America Tower.[3][55] The facade was designed in the neo-Georgian style by architects Paul R. Allen and Ingalls & Hoffman.[3][56][57] The facade measures about 50 feet (15 m) tall, 86 feet (26 m) wide, and 4 feet (1.2 m) thick.[58] Because of the theater's landmark status, the facade could not be damaged in any way,[59] nor could it be removed temporarily.[60] Furthermore, even though the theater was reconstructed as part of the Bank of America Tower's construction, the new theater could not be any taller than the old facade.[59] The landmark facade was temporarily attached to a three-story steel support frame when the tower was built.[59][60][61] The theater facade protrudes from the glass curtain wall that surrounds it on all sides.[42][62] Above the theater facade is a billboard attached to the curtain wall.[42]  The theater's ground-story facade consists of a water table made of granite, above which is a brick facade. There are five rectangular doorways at the center of the facade, each containing a recessed pair of metal doors; above these doorways are stone lintels with urn symbols at the center and rosettes to the far left and right. There is a marquee above the three center bays of the ground story.[63] As of September 2010[update], the marquee displays the words "Stephen Sondheim", reflecting its rename from Henry Miller's Theatre.[64] The five center openings are flanked by a pair of segmental-arched gateways with wrought-iron gates; paneled keystones above their centers; and wrought-iron lanterns flanking each side.[63] These gateways formerly were the theater's alleys.[57][65] The rest of the landmark theater facade is made of red brick in common bond and is split into two end pavilions flanking five vertical bays. Each bay is delineated by projecting brick pilasters topped by decorated Corinthian-style capitals of terracotta. The five center bays have rectangular window openings at the second story, with stone keystones and brick voussoirs atop each window, as well as iron balconies curving outward. On the third story, there are three round-arched windows at the center, flanked by two blind openings with brick infill; they also have stone keystones and brick voussoirs. The end pavilions have arched brick niches at the second story and terracotta roundels on the third story. Above that is a terracotta frieze with the name "Henry Miller's Theatre" carved in the center and triangular pediments above the end pavilions. A parapet runs at the roof of the landmark facade.[63] Structural featuresSubstructureUnderneath the site is durable Hartland bedrock.[9] The southern lot line is adjacent to the 42nd Street Shuttle's cut-and-cover tunnel. The eastern lot line is adjacent to the IND Sixth Avenue Line tunnel (used by the B, D, F, <F>, and M trains), which was built using both cut-and-cover and mining.[8] Before the tower was constructed, the contractors made two sets of borings to extract samples of the composition of the ground. The borings found that the rock profiles of the site varied widely. Around Sixth Avenue, there was generally competent rock at a depth of 10 to 20 feet (3.0 to 6.1 m), but near the former stream bed on the western boundary, the rock had a dip extending about 50 feet (15 m) deep. The hard rock mostly consists of gneiss and schist, but there are rock joints that slope downward into the building's site.[66] The foundation consists of spread footings under the building's columns. An existing foundation wall on the eastern lot line was repurposed into a retaining wall, which holds back the soil above the layers of rock. The retaining wall is stabilized by a set of pillars spaced every 10 feet (3.0 m) and measuring 4 by 4 feet (1.2 by 1.2 m). A rock anchor is used to tie down each of these pillars. During construction, rock bolts were used to reinforce the cut-and-cover section of the subway tunnel under Sixth Avenue, while a combination of anchors and bolts was used to reinforce the mined section of the tunnel.[67] Seismometers were used to record movement around the tunnel.[68] SuperstructureThe Bank of America Tower's superstructure is built with steel and concrete.[41] The mechanical core, containing the stairs and elevators, is surrounded by concrete shear walls that encase a light steel framework. The rest of the structure is made of steel.[69][70] The mixture used in the superstructure's concrete is 45 percent slag, a byproduct of blast furnaces.[34][71][72] By using slag, the builders avoided emitting 50,000 metric tons (49,000 long tons; 55,000 short tons) of carbon dioxide greenhouse gas, which would have been produced through the normal cement manufacturing process.[34] The slag accounts for 68,000 cubic yards (52,000 m3) of the concrete used in the Bank of America Tower. In addition, 60 percent of the steel in the superstructure is recycled material.[73] A large proportion of the building's materials were sourced from within 500 miles (800 km) of New York City.[73][74] Vertical loads from the center of the building are distributed into the tower's core. The steel beams rest directly on the tops of the two highest elevator banks, where the loads are relatively small. Two perpendicular supporting trusses are placed above the two lowest elevator banks to distribute the larger vertical loads from higher floors.[75] Diagonal columns are also used to carry vertical loads inward.[43][69] The centers of the perimeter columns are spaced every 20 feet (6.1 m) and begin sloping inward at different heights.[70] At locations where vertical and diagonal columns intersect, tie beams and connections are installed to counteract horizontal loads. Horizontal trusses are used at the 3rd, 4th, 11th, and 12th stories, where the southeast corner columns all slope inward; the trusses carry lateral loads from the columns to the mechanical core's shear walls.[69] Box columns, measuring 24 by 24 inches (610 by 610 mm), are used at the base to carry the higher loads of the upper stories.[70] The floor slabs are made of 3-inch (76 mm) composite metal decks. The slab-to-slab distance, or the height between different stories' floor slabs, is 14.5 feet (4.4 m).[76] The perimeter of the tower stories is typically 40 feet (12 m) from the core, and the filler beams underneath the floor slabs are 18 inches (460 mm) deep. At the northeast and southwest corners, the perimeter is 55 feet (17 m) from the core, so these beams are cantilevered from the perimeter. The engineers considered using thicker filler beams and additional columns, but these were both rejected because they reduced the amount of available space. The tips of the cantilevered beams are connected vertically to distribute live loads among several stories.[27] Above Stephen Sondheim Theatre, plate girders transfer the vertical loads to the side walls of the theater's auditorium. A Vierendeel truss was also installed so views from the facade's windows were not blocked.[60] The screen walls above the tower's roof are cantilevered by beams measuring 8 or 10 inches (200 or 250 mm) thick and 8 inches wide.[70] The beams were designed to be as thin as possible while also supporting the mechanical equipment.[77] The tower's architectural spire is about 300 feet (91 m) tall. It contains a cylindrical mast that extends from the roof, where it measures 58 inches (1,500 mm) wide, and tapers to a width of 26 inches (660 mm) at its pinnacle.[76] Sections of pipe, measuring 12.75 inches (324 mm) in diameter, are bolted to the mast in a triangular pattern.[60] The spire is lit by LEDs,[78] which the general public can control through Spireworks, a free app. The app allows five users at a time to control the lights for two-minute periods.[79][80] Mechanical and environmental featuresThe tower has a cogeneration plant, which can provide up to seventy percent[b] of the building's energy requirements.[54][81][82] It is variously cited as being capable of 4.6 megawatts (6,200 hp),[44][54][81] 5.1 megawatts (6,800 hp),[34] or 5.4 megawatts (7,200 hp).[48][82] The cogeneration plant is powered by natural gas[44] and is used to power the offices and the core mechanical systems, such as lights and elevators.[34] Because of the building's high peak-hour energy use, the Durst Organization estimated that the cogeneration plant could provide 35 percent of the tower's energy needs during peak times.[83] There is also a wind turbine on the roof's shorter spire.[28][53] A very small proportion of the power is provided by a 1,000-U.S.-gallon (3,800 L; 830 imp gal) tank of organic waste. On average, the tank receives 2 short tons (1.8 long tons; 1.8 t) of organic waste every day, which is turned into methane, thereby generating 75 kilowatts (101 hp) a day.[34] The Bank of America Tower is also connected to the main New York City power grid but, unlike all other Midtown skyscrapers, it is linked to an electrical substation in Lower Manhattan.[84]  There is an ice-storage plant in the basement, which creates ice at night, when energy costs are lower than in the daytime.[54][81][18] It consists of 44 tanks that can each hold 625 cubic feet (17.7 m3) of glycol.[18] Water is combined with glycol and then kept inside the tanks at around 27 °F (−3 °C).[85] The air-conditioning system consists of various chillers ranging between 850 and 1,200 short tons (760 and 1,070 long tons; 770 and 1,090 t). The air-conditioning system is designed so different chillers operate only as necessary, thereby reducing energy consumption.[44] For heating, the groundwater in the underlying bedrock is kept at a consistent 53 °F (12 °C). Heat is drawn from the bedrock during the winter, while excess heat is absorbed into the bedrock during summer.[34] There are air-intake openings just above the top of the base.[53][c] Further air intake openings are placed 850 feet (260 m) above ground, near the roofline.[29] These openings filter the air intake throughout the building, distribute it through the interior, and then filter the air again before ventilating it.[53][18] The filters over the intake openings have a minimum efficiency reporting value of 15, making them among the most efficient filters on the MERV scale. The filtration systems are able to extract 95 percent of particulates, in addition to ozone and volatile organic compounds. This is in contrast to similar systems being manufactured around the time of the Bank of America Tower's construction, which only extracted 35 to 50 percent of particulates and minimal ozone or volatile organic compounds.[29] The Bank of America Tower is designed so it uses 45 percent less water from the New York City water supply system than conventional buildings of similar size.[18] The tower contains a rooftop greywater system, which captures rainwater for reuse.[34][48][18] When the building was being constructed, New York City received an average of 48 to 49 inches (1,200 to 1,200 mm) of rainfall every year, which amounted to an annual rainwater collection of 2.6 million U.S. gal (9,800,000 L).[34][49] Additionally, about 5,000 U.S. gallons (19,000 L; 4,200 imp gal) of groundwater is collected daily.[49] Four holding tanks, each with a capacity of 60,000 U.S. gallons (230,000 L; 50,000 imp gal),[48] are placed at different heights throughout the building.[48][86] The rainwater is used for functions such as flushing the toilets;[48] all of the building's 300 toilets contain dual-flush handles.[87] Only wastewater from the toilets is sent to the city's sewage system, while the rest is treated and recycled, reducing sewage outflows by 95 percent compared to similarly sized building.[18] Also as a water-saving measures, none of the building's urinals use water.[44][53] On average, each of the 200 urinals saves about 40,000 U.S. gallons (150,000 L) of water annually.[53] Interior The tower includes three escalators and a total of 52 elevators.[74][88] Schindler Group manufactured the elevators and escalators.[88] The elevators from the base to the tower stories are grouped in five elevator banks: two at the ground level, for general tenants, and three on the second story, for Bank of America workers only.[50] Four of the elevator banks contain eight cabs each, while the fifth bank of elevators contains six cabs.[88] The elevators contain a destination dispatch system, wherein passengers request their desired floor before entering the cab.[88][89] LobbyThe lobby is 38 feet (12 m) tall and is visible from Sixth Avenue. The elevator core and security checkpoints to the upper stories are next to the lobby.[44] The lobby is decorated with materials such as Jerusalem stone and cream-colored leather paneling.[50][54] About 9,000 square feet (840 m2) of Jerusalem stone was used.[90] The floor of the lobby is made of white granite and contains air conditioning and radiant heating, while the west wall facing Sixth Avenue is clad in stone.[54] The white granite was imported from Tamil Nadu in India and covered 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) total, including 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2) of floor tiles.[91] The lobby ceiling is made of carbonized bamboo. According to Cookfox, the lobby's design was intended to form "a layered connection to the public realm of Bryant Park".[54] Cookfox also used dark oxidized stainless steel for the lobby, in contrast to the lighter aluminum and stainless steel in public areas or the "warmer" colors used in the tower's core. The entrance to each elevator bank contains dark-steel doorways. A 40-foot-wide (12 m) by 16-foot-tall (4.9 m) arch marks the entrance to the general tenants' elevators on the north side of the lobby.[50] Dark steel was also used for the surfaces of the security desks and turnstiles at the security checkpoints.[92] Structurally, the lobby is designed with columns that could withstand additional weight if one of the columns was damaged.[7] Other lower-level spaces The building's Urban Garden Room at 43rd Street and Sixth Avenue, north of the lobby, is open to the public as part of the city's privately owned public space (POPS) program.[44][93] It was designed by Margie Ruddick and sculpted by her mother Dorothy Ruddick.[93][94] The room covers 3,500 square feet (330 m2)[44] and is surrounded by a glass wall that separates it from the lobby.[95] The room contains plants such as ferns, mosses, and lichen, some of which are planted on structures like a 25-foot-tall (7.6 m) arch or a 7-foot-tall (2.1 m) slab.[93][96] Dorothy Ruddick had created the four sculptures in the space shortly before her death.[97] The Durst Organization had wanted to create an actual garden, but it dismissed this idea because the sunlight would not have been sufficient to illuminate a garden. Shortly after the garden opened in 2010, about three-fourths of the plants were replaced because they had died.[93] The interior of Henry Miller's Theatre, which was not protected by landmark status, was completely rebuilt to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[59] Its interior was designed to meet LEED Gold standards.[49] The rebuilt theater has 1,055 seats,[49][55][98] compared to the 955 seats of the original theater.[98] Designed by Cookfox, the theater has artifacts from the original structure.[98][99] For the theater's reconstruction, Severud and Tishman had to excavate the theater as much as 70 feet (21 m) below street level, since the new theater could not rise above the old facade.[59] The theater is acoustically isolated from the upper stories to avoid disrupting Bank of America's traders above.[60] There are several commercial spaces at the Bank of America Tower's base. One of these is a Burger & Lobster restaurant in the basement, first floor, and second floor, with an entrance from the pedestrian arcade that connects 42nd and 43rd Streets.[100] The restaurant is designed with 24-foot-tall (7.3 m) windows facing 43rd Street; a staircase connecting the entrance and second-floor dining room; a lobster sculpture; and red dining booths.[101][102] A Bank of America branch is also located at 115 West 42nd Street.[103] There is also a Starbucks on the 43rd Street side.[104]  An enclosed pedestrian walkway, known as Anita's Way, runs through the western end of the building and connects 42nd and 43rd Streets.[49][105] Measuring 30 feet (9 m) wide and 30 feet high,[70] it serves as an entrance to Stephen Sondheim Theatre and as a performance space.[106] The passageway is named after Anita Durst, Douglas Durst's daughter and a leader of arts organization chashama.[105] The organization had occupied a site on 42nd Street that was demolished to make way for the Bank of America Tower.[14][11] Office spaceEach of the office floors has a ceiling measuring 9.5 feet (2.9 m) high.[48][49] The office stories use a raised floor structural system to allow utilities and mechanical systems to be built underneath the floors.[74][86][107] The finished office floor is about 14 inches (360 mm) above the floor slab.[76] The office stories also contain dropped ceilings, above which are some of the mechanical systems.[108] Air conditioning is pumped through the underfloor plenum system.[18][53] The interior lighting system is designed to emphasize the southeast-corner chamfer at night.[32][78] The upper stories span up to 90,000 square feet (8,400 m2).[46] Bank of America's offices, spanning the first through 36th and the top floor,[109] were designed by Gensler.[23][32] The bank required 50 foot-candles of lighting for its offices, but conventional light fixtures could not do this without wasting energy. As a result, a custom lighting fixture was manufactured for the bank's offices, which could be controlled by a dimmer, though the fixtures could save energy regardless of the presence of a dimmer.[32] Partitions between work cubicles are designed to be 48 inches (1,200 mm) tall, and furniture and carpets were designed with a "warm" brownish color scheme. The offices themselves are arranged in 5-foot-wide (1.5 m) modules to align with the subdivisions of the facade and ceiling. For offices placed near the tower's perimeter, furniture and opaque partitions were arranged perpendicularly to the curtain wall.[107] One-third of all the space in the building was devoted to the bank's trading floors in 2013.[35][36] HistoryPlanningThe Durst family had started acquiring property on the city block bounded by Broadway, Sixth Avenue, and 42nd and 43rd Streets in 1967, when Seymour Durst bought a building that housed White's Sea Food Restaurant.[110] Seymour Durst planned to redevelop the area east of Times Square with office skyscrapers, but he canceled these plans in 1973 amid a declining office market.[111] Several other failed proposals followed for what would become 1 Bryant Park's site. One such proposal took place in the early 1980s, when Seymour Durst proposed selling his land to Joseph E. and Ralph Bernstein, but reneged after learning that the Bernsteins were acting on behalf of Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos, creating acrimony between the Dursts and the Bernsteins.[15] Further proposals for the current site were made in 1987, when a tower for Morgan Stanley was proposed just before the Black Monday, and in 1990, when a building for Chemical Bank was proposed.[110]  Seymour Durst erected the National Debt Clock on one building at the site in 1989.[112] By the next year, Seymour Durst had acquired 20 lots, including the Henry Miller Theater and the Hotel Diplomat.[15] Though Seymour Durst died in 1995, his son Douglas Durst continued to acquire land on the block, developing 4 Times Square on the western half in the late 1990s.[110] Douglas's daughter Anita convinced him to allow her arts organization chashama to temporarily use one of the empty storefronts on the site.[11] In 1998, the New York City and state governments offered to condemn the remainder of the block via eminent domain so Durst could acquire the lots and develop a headquarters for Nasdaq there.[113] The Bernsteins filed a lawsuit against New York state to prevent their land from being seized through eminent domain.[114] The Nasdaq plan was canceled the next year.[115] Early plansIn 1999, the mayoral administration of Rudy Giuliani encouraged Douglas Durst to build a 2-million-square-foot (190,000 m2) tower and a 1,500-seat Broadway theater on the site. At the time, Durst had acquired 85 percent of the city block. Joseph Bernstein owned four lots on 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue, while Susan Rosenberg owned a lot on the southwest corner of 43rd Street and Sixth Avenue. In addition, the Brandt family owned the Pix Theater and Richard M. Maidman owned the Remington Building on 42nd Street.[110] Durst began negotiating with the Brandts for their land,[116] and he started discussing with real estate company Tishman Speyer to jointly develop the site.[117] By late 2000, Durst and Tishman Speyer were nearing an agreement to develop a tower on the site.[118] The planned office tower would be called "1 Bryant Park", though Durst was still negotiating to acquire the rest of the block.[10][118] By early 2001, only the Bernstein, Maidman, and Rosenberg lots remained to be acquired, though Maidman and Bernstein were loath to sell to Durst.[119] This prompted the government of New York state, under the Empire State Development Corporation, to consider acquiring the remaining land via eminent domain.[119][120] Bernstein's Triline Trading filed a lawsuit against the Empire State Development Corporation in April 2001. Triline alleged that the state was conspiring with Durst to depress the value of the Bernstein plots.[10] The Maidmans, meanwhile, were trying to redevelop their building at 113 West 42nd Street into a hotel designed by Isaac Mizrahi.[12][119] The family had torn up a contract that would have allowed Durst an option to buy their property in exchange for a billboard on Maidman's building. Durst filed complaints against Maidman in June 2001, alleging that debris from Maidman's building was falling onto land that Durst owned, causing "considerable damage".[119] Durst's failed attempts to buy out Bernstein and Maidman resulted in two non-contiguous plots: the corner of 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue, completely surrounded by Bernstein's plots to the north and west, as well as the remainder of the block, which encircled 113 West 42nd Street between Bernstein's property to the east and 4 Times Square to the west. 1 Bryant Park, which would occupy the plot around 113 West 42nd Street, was to cost $600 million and contain 1.2 million square feet (110,000 m2). Durst also planned to build a 30-story hotel at the corner of 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue for $60 million.[121] Despite the September 11 attacks later in 2001, Durst proceeded with plans to build 1 Bryant Park to designs by Fox & Fowle Architects.[122] Shortly after the attacks, Durst told city and state officials that he was willing to develop the 1 Bryant Park site, even if it meant a lower rate of return.[123] Durst proposed that the state condemn Bernstein's and Maidman's lots to increase the size of the skyscraper he wished to build. State officials expressed interest in this plan.[122] Joseph Bernstein also withdrew his lawsuit against the state.[114] Bank of America and final plansIn December 2001, Richard Maidman agreed to sell his building to Durst, who had offered $13 million.[124][125] Though Maidman's building was in the process of being converted to a hotel, Maidman said he was prompted to sell during the city's recovery from the September 11 attacks, saying that he did not wish to prevent office space from being developed.[125] Durst had already received $115 million in credit from the Bank of New York and other lenders, which in theory allowed him to start demolishing the site before a tenant had been secured or a construction loan had been obtained.[125] Susan Rosenberg continued to occupy the corner of Sixth Avenue and 43rd Street through 2003, though she was willing to enter into a contract with Durst to sell the building there.[126] However, Rosenberg said she wanted to be the last tenant to sell.[114] Durst negotiated with Joseph Bernstein who, along with some partners, owned the remaining parcels on the block.[126] Fox & Fowle were still the architects of the proposed tower through at least early 2003.[127] Meanwhile, by March 2003, Bank of America was looking for a new headquarters for its operations in Midtown, which would allow the bank to consolidate its New York City offices from several locations. One site under consideration was Durst's lot at Bryant Park, though the bank was also discussing with other developers including Brookfield Properties.[128] By May 2003, Bank of America was close to signing an agreement with Durst to occupy half the proposed office tower.[114][129] The city government had supported the construction of the tower, while the state government was considering condemning the remaining land.[114] This drew opposition from Rosenberg and from Bernstein's partnership, who said they would rather negotiate with Durst than have their property seized by condemnation. Further, Bernstein was also planning to redevelop his property with a 30-story hotel and wished to offer Durst $40 million for the corner of 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue.[130] In mid-2003, Durst announced he would request $650 million in tax-free Liberty bonds, allocated for September 11 recovery efforts, to finance the building's construction. This request, along with a similar one for the New York Times Building three blocks southwest, received public criticism.[131] At a hearing the September, members of the public expressed their opposition to the usage of tax-free bonds for the project.[132][133] Some opponents criticized Durst's donations to New York governor George Pataki, which they saw as corruption. Other critics said the bonds should be used for projects in Lower Manhattan, which was more heavily affected by the attacks, instead of Midtown.[134] The city's Industrial Development Agency approved the bonds anyway.[135][136] Bernstein spoke against the planned use of eminent domain to seize his land.[137] The New York state government told Durst it could use eminent domain on the remaining lots, even though the land to be condemned was not in a "blighted" area, if he could sign an anchor tenant for the planned building.[138] Durst and Bank of America announced in December 2003 that they would jointly develop a 51-story tower at 1 Bryant Park, to be designed by Cookfox.[139][140] The bank would occupy about half of the building's planned 2.1 million square feet (200,000 m2) of office space.[139] Shortly afterward, Bernstein and his partners agreed to sell their land for $46 million, or $384 per square foot ($4,130/m2), to Durst and Bank of America.[126][141] Only the corner lot at 43rd Street and Sixth Avenue remained to be acquired.[141] The announcement of Bank of America's tenancy had spurred interest in office space leasing among smaller companies,[142] as well as investment in the stretch of 42nd Street between Bryant Park and Times Square.[143] 1 Bryant Park was also to be one of several buildings around Times Square being developed for financial services companies.[144] Durst notified the operators of Henry Miller's Theatre that the theater would have to be closed and demolished to make way for 1 Bryant Park's construction.[145] Consequently, the old theater closed in January 2004.[146] By that month, Durst had acquired the final property and was planning to move the National Debt Clock.[147] Construction Durst and Bank of America received final approval to issue Liberty Bonds for the building's construction in February 2004.[148] Because of the high cost of steel during early 2004, the Durst Organization decided not to proceed with construction until later that year.[149] Meanwhile, all tenants were obliged to move out by that February, with demolition to begin that May.[11] A groundbreaking ceremony for the building was hosted on August 2, 2004.[150][151] The groundbreaking ceremony occurred the day that terror threats were made against some of the city's major banks and finance companies, leading Pataki to say, "This is probably the best day we could choose to break ground."[151] Shortly after the groundbreaking, a frame was built to support the facade of Henry Miller's Theatre.[58][60][61] The theater's interior was demolished using manual tools, and the contractors installed sensors to detect any vibrations on the facade.[59][61] After construction began, the Durst Organization reported a high amount of demand for the remaining office space. Though Bank of America's space would cost the bank less than $100 per square foot ($1,100/m2), prospective tenants offered to move into the remaining space even at rents of over $100 per square foot.[152] Among those was law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore which, in early 2005, expressed an interest in relocating to the building.[153] Bank of America itself was looking for several hundred thousand square feet near its new offices.[154][155] In early 2006, Bank of America leased another 522,000 square feet (48,500 m2) of space, bringing its total occupancy in the building to 1.6 million square feet (150,000 m2).[109][156] Bank of America planned to operate six trading floors of between 43,000 and 90,000 square feet (4,000 and 8,400 m2), as well as the first through 36th stories and the top floor. At the time, only 450,000 square feet (42,000 m2) of space remained unoccupied.[109] Law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld had leased some space by late 2006,[157][158] paying more than $100 per square foot.[157][159] Among the other tenants at the Bank of America Tower was Generation Investment Management, a firm cofounded by environmentalist and former U.S. vice president Al Gore.[160][161] By the middle of that year, the building was almost fully pre-leased, with average asking rents of $150 per square foot ($1,600/m2).[162] Durst and Bank of America announced in May 2007 that it planned to refund the $650 million of Liberty Bonds that had been distributed for the building's construction.[163] Though the refund was approved,[164] the financial crisis of 2007–2008 delayed the refinancing for over a year.[165] The building was topped out with a ceremony on June 26, 2007.[166] A construction container fell from a crane in October 2007, causing damage to the tower and injuring eight people.[167][168] After the accident, the city government ordered a temporary halt to the construction of the Bank of America Tower.[169] The building's spire was installed by December 15, 2007.[170] By mid-2008, the scaffolding over the facade of Henry Miller's Theater was being dismantled.[171] Several construction accidents occurred that year. In August 2008, a 1,500-pound (680 kg) glass panel fell onto a sidewalk, hurting two passersby.[172] The window had gotten stuck near the top of the tower while it was being pulled by a winch; this led the New York City Department of Buildings to issue three violations. A Tishman spokesman said 9,400 facade panels had already been installed at the time.[173] A month later, a debris container fell, shattering a facade panel and causing several shards of glass to fall to the street, though no one was injured.[174] Yet another incident occurred that November, when a worker fell from a scaffold and was injured.[175] UsageOpening The first workers started moving into the Bank of America Tower in 2008.[176] The building was refinanced in June 2009 with a $1.28 billion package from a group of lenders led by Bank of America; this financing replaced the Liberty Bonds.[177][178] The Aureole restaurant opened within the base of the building later that year.[179][180] Also in late 2009, Henry Miller's Theatre reopened within the base of the Bank of America Tower.[181] By January 2010, signs with the building's name were being erected at the entrances.[182] Durst and Bank of America held a grand opening for the tower in May 2010.[42][183] At the ribbon-cutting ceremony, Gore praised mayor Michael Bloomberg and other people involved in the project.[35][184] The building was certified as a LEED Platinum office building that month, except for the theater, which was certified as LEED Gold.[26][49] This made the Bank of America Tower the first U.S. office building to be certified as platinum.[185] At the time, the building was appraised at $2.2 billion.[186] Shortly afterward, Durst and Bank of America refinanced $1.275 billion in construction loans with Liberty bonds and a commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS) loan from Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase.[186][187] Henry Miller's Theatre at the building's base was renamed the Stephen Sondheim Theatre that year, after musical composer Stephen Sondheim.[181][188] 2010s to presentOnly a few years before the Bank of America Tower's construction, the surrounding area had contained discount stores and homeless encampments, but its completion caused an immediate change to the vicinity.[189] Following the building's completion, asking rents at many Bryant Park buildings rose to $100 per square foot.[190] After the tower was completed, Sam Roudman of The New Republic magazine reported that the Bank of America Tower used twice as much energy overall as the Empire State Building due to the Bank of America Tower's high energy usage.[35][36] According to Roudman, although platinum was the highest LEED green-building certification available, the Bank of America Tower emitted more greenhouse gases than all other similarly-sized buildings in Manhattan.[35] Bryan Walsh of Time magazine wrote that it was the high energy usage of the building's trading floors, rather than the building itself, that created such high emissions.[36] Among the early retail tenants was Starbucks, which leased a location in the base in 2011.[191] The Bank of America Tower lost power during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, as it was the only Midtown skyscraper connected to an electrical substation downtown.[84] In mid-2013, the Durst Organization employed Brooklyn Grange Rooftop Farm to install and maintain two honeybee hives on the building.[192] Also during 2013, asset management firms QFR Management and TriOaks Capital Management, as well as insurance underwriter Ascot Underwriting and hedge fund QFR, signed leases for space in the building.[191] In 2016, Burger & Lobster signed a lease for a restaurant space in three stories next to the Stephen Sondheim Theatre. This brought the Bank of America Tower to full occupancy.[101][193] Durst and Bank of America refinanced the tower in 2019 for $1.6 billion, composed of a $950 million CMBS from Bank of America as well as $650 million of Liberty Bonds.[194][195] At the time, Bank of America occupied the largest share of space in the building, though investment manager Marathon Asset Management, law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, and Stephen Sondheim Theatre's operator Roundabout Theatre Company also took up some space.[196] The building was appraised the same year at over $3.5 billion, ranking it among the most valuable office buildings in the city.[197] Starbucks signed a new lease at the building's base in late 2020.[104] That year, the Aureole restaurant closed and was replaced by the Charlie Palmer Steak restaurant.[198][199] ReceptionWhen the building was being developed, a writer for The Village Voice said that the tower "looks like it's going to be alien too, with its reflective mirror sides".[200] David W. Dunlap of The New York Times said that the tower, "rising like an icy stalagmite, is a three-dimensional reminder that big banks now dominate New Yorkers' consciousness."[201] Justin Davidson of New York magazine called the Bank of America Tower "a bulky glass stele that executes a modest twist to lend itself an air of grace".[202] Conversely, Christopher Gray of the Times called the tower a symbol of how "Bryant Park, once synonymous with the worst of New York City, has become a brand name".[203] Another writer for the same newspaper said the skyscraper was a "psychological and economic lift to a city that was still reeling from the destruction of the World Trade Center" in the September 11 attacks.[138] The Bank of America Tower was the subject of several exhibits and media works during its development. For example, the building's environmental features were displayed in a Skyscraper Museum exhibit in 2006.[204] These features were also described in a podcast that the New York Academy of Sciences launched in June 2008.[205] Furthermore, in November 2008, the building was featured in its own documentary on the National Geographic Channel.[206][207] In June 2010, the Bank of America Tower was the recipient of the 2010 Best Tall Building Americas award by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.[208] Additionally, the building received an Award of Merit during the 2011 Annual Lumen Gala, a convention for New York City's lighting industry.[209] See also

ReferencesNotes

Citations

Sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Bank of America Tower (Manhattan).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||