|

Ancrene Wisse

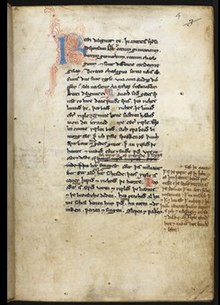

Ancrene Wisse (/ˌæŋkrɛn ˈwɪs/; also known as the Ancrene Riwle[note 1] /ˌæŋkrɛn ˈriːʊli/[1] or Guide for Anchoresses) is an anonymous monastic rule (or manual) for anchoresses written in the early 13th century. The work consists of eight parts: divine service, keeping the heart, moral lessons and examples, temptation, confession, penance, love, and domestic matters. Parts 1 and 8 deal with what is called the "Outer Rule" (relating to the anchoresses' exterior life), while Parts 2–7 deal with the "Inner Rule" (relating to the anchoresses' interior life). It is written in Middle English, and was translated into Anglo-Norman and Latin. CommunityThe adoption of an anchorite life was widespread all over medieval Europe, and was especially popular in England. By the early thirteenth century, the lives of anchorites or anchoresses were considered distinct from that of hermits. The hermit vocation permitted a change of location, whereas the anchorites were bound to one place of enclosure, generally a cell connected to a church. Ancrene Wisse was originally composed for three sisters who chose to enter the contemplative life. In the early twentieth century, it was thought that this might be Kilburn Priory near the medieval City of London, and attempts were made to date the work to the early twelfth century and to identify the author as a Godwyn, who led the house until 1130.[2] More recent works have criticised this view, most notably because the dialect of English in which the work is written clearly originates from somewhere in the English West Midlands, not far from the Welsh border. In 1935 the Early English Text Society which was led by Sir Israel Gollancz and managed by Mabel Day decided to publish editions of the Ancrene Wisse. Day advised on several editions and she worked on the Nero MS version which had been transcribed by J. A. Herbert. The principles which she established are said to have governed all the later editors.[3] Geoffrey Shepherd in the production of his edition of parts six and seven of the work showed that the author's reading was extensive. Shepherd linked the author's interests with those of a generation of late twelfth-century English and French scholars at the University of Paris, including Peter the Chanter and Stephen Langton. Shepherd suggested that the author was a scholarly man, though writing in English in the provinces, who was kept up to date with what was said and being written in the centres of learning.[citation needed] EJ Dobson argues that the anchoresses were enclosed near Limebrook in Herefordshire, and that the author was an Augustinian canon at nearby Wigmore Abbey in Herefordshire named Brian of Lingen.[4] Bella Millett has subsequently argued that the author was in fact a Dominican rather than an Augustinian.[citation needed] The revision of the work contained in the manuscript held at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (used by most modern translations) can be dated between 1224 and 1235.[5] The date of the first writing of the work tends to depend upon one's view of the influence of the pastoral reforms of the 1215 Fourth Lateran Council. Shepherd believes that the work does not show such influence, and thinks a date shortly after 1200 most likely. Dobson argues for a date between 1215 and 1221, after the council and before the coming of the Dominicans to England. The general contours of this account have found favour in modern textbook assessments of the text.[note 2] Language and textual criticismThe version of Ancrene Wisse contained in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, is known as MS 402. It was written in an early Middle English dialect known as 'AB language' where 'A' denotes the manuscript Corpus Christi 402, and 'B' the manuscript Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Bodley 34. Manuscript Bodley 34 contains a set of texts that have become known as the "Katherine Group": Seinte Katerine, Seinte Margarete, Seinte Iuliene, Hali Meiðhad and Sawles Warde.[6] Both manuscripts were written in the AB language, described by J. R. R. Tolkien as "a faithful transcript of some dialect...or a 'standard' language based on one' in use in the West Midlands in the 13th century." [7] The word Ancrene itself still exhibits a feminine plural genitive inflection descended from the old Germanic weak noun declension; this was practically unknown by the time of Chaucer. The didactic and devotional material is supplemented by illustrations and anecdotes, many drawn from everyday life.[8] Ancrene Wisse is often grouped by scholars alongside the Katherine Group and the Wooing Group—both collections of early Middle English religious texts written in AB language. Surviving manuscriptsThere are seventeen surviving medieval manuscripts containing all or part of Ancrene Wisse. Of these, nine are in the original Middle English, four are translations into Anglo-Norman, and a further four are translations into Latin. The shortest extract is the Lanhydrock Fragment, which consists of only one sheet of parchment.[9] The extant manuscripts are listed below.

Although none of the manuscripts is believed to be produced by the original author, several date from the first half of the 13th century. The first complete edition edited by Morton in 1853 was based on the British Library manuscript Cotton Nero A.xiv.[11] Recent editors have favoured Corpus Christi College, Cambridge MS 402 of which Bella Millett has written: "Its linguistic consistency and general high textual quality have made it increasingly the preferred base manuscript for editions, translations, and studies of Ancrene Wisse."[12] It was used as the base manuscript in the critical edition published as two volumes in 2005–2006.[13] The Corpus manuscript is the only one to include the title Ancrene Wisse.[6] The Ancrene Wisse was partly retranslated from French back into English and reincorporated in the late 15th-century Treatise of Love.[14] The fifteenth-century Treatise of the Five Senses also makes use of material from the work. Notes

References

Sources

Editions

Further reading

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Ancrene Wisse. |