|

American ancestry

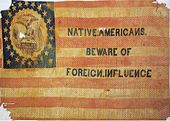

In the demography of the United States, some people self-identify their ancestral origin or descent as "American", rather than the more common officially recognized racial and ethnic groups that make up the bulk of the American people.[2][3][4] The majority of these respondents are visibly white and do not identify with their ancestral European ethnic origins.[5][6] The latter response is attributed to a multitude of generational distance from ancestral lineages,[3][7][8] and these tend be Anglo-Americans[7] of English, Scotch-Irish, Welsh, Scottish or other British ancestries, as demographers have observed that those ancestries tend to be recently undercounted in U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey ancestry self-reporting estimates.[9][10] Although U.S. census data indicates "American ancestry" is most commonly self-reported in the Deep South, the Upland South, and Appalachia,[11][12] a far greater number of Americans and expatriates equate their national identity not with ancestry, race, or ethnicity, but rather with citizenship and allegiance.[13][8] EtymologyLook up American in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. The earliest attested use of the term "American" to identify an ancestral or cultural identity dates to the late 1500s, with the term signifying "the indigenous peoples discovered in the Western Hemisphere by Europeans."[14] In the following century, the term "American" was extended as a reference to colonists of European descent.[14] The Oxford English Dictionary identifies this secondary meaning as "historical" and states that the term "American" today "chiefly [means] a native (birthright) or citizen of the United States."[14] Historical reference President Theodore Roosevelt asserted that an "American race" had been formed on the American frontier, one distinct from other ethnic groups, such as the Anglo-Saxons.[15]: 78, 131 He believed "(t)he conquest and settlement by the whites of the Indian lands was necessary to the greatness of the race...."[15]: 78 "We are making a new race, a new type, in this country."[15] Roosevelt's "race" beliefs were not unique in the 19th and early 20th century.[16][17][18][19][20] Professor Eric Kaufmann has suggested that American nativism has been explained primarily in psychological and economic terms to the neglect of a crucial cultural and ethnic dimension. Kauffman contends American nativism cannot be understood without reference to the theorem of the age that an "American" national ethnic group had taken shape prior to the large-scale immigration of the mid-19th century.[18] "Nativism" gained its name from the "Native American" parties of the 1840s and 1850s.[21][22] In this context, "Native" does not mean indigenous or American Indian, but rather those descended from the inhabitants of the original Thirteen Colonies (Colonial American ancestry).[23][24][18] These "Old Stock Americans," were predominantly Protestants from England, Sweden, the Netherlands, and even modern-day Russia and Finland. They saw Catholic immigrants as a threat to traditional American republican values, as they were loyal to the papacy.[25][26] This form of American nationalism is often identified with xenophobia and anti-Catholic sentiment.[27]  Nativist outbursts occurred in the Northeast from the 1830s to the 1850s, primarily in response to a surge of Catholic immigration.[28] The Order of United American Mechanics was founded as a nativist fraternity, following the Philadelphia nativist riots of the preceding spring and summer, in December 1844.[29] The New York City anti-Irish, anti-German, and anti-Catholic secret society the Order of the Star Spangled Banner was formed in 1848.[30] Popularised nativist movements included the Know Nothing or American Party of the 1850s and the Immigration Restriction League of the 1890s.[31] During the antebellum period (pre-Civil War), between 1830 and 1860, Americanism acquired a restrictive political meaning due to nativist moral panics.[32] Nativism would eventually influence Congress;[33] in 1924, legislation limiting immigration from Southern and Eastern European countries was ratified, also quantifying previous formal and informal anti-Asian previsions, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907.[34][35] Modern usageStatistical dataAccording to U.S. Census Bureau; "Ancestry refers to a person's ethnic origin or descent, 'roots,' or heritage, or the place of birth of the person or the person's parents or ancestors before their arrival in the United States."[36]  German English Norwegian Dutch Finnish Irish French Italian Mexican Native Spanish American African American Puerto Rican According to 2000 U.S. census data, an increasing number of United States citizens identify simply as "American" on the question of ancestry.[37][38][39] The Census Bureau reports the number of people in the United States who reported "American" and no other ancestry increased from 12.4 million in 1990 to 20.2 million in 2000.[40] This increase represents the largest numerical growth of any ethnic group in the United States during the 1990s.[2] The state with the largest increase over the past two census was Texas, where in 2000, over 1.5 million residents reported having "American ancestry."[41] In the 1980 census, 26% of United States residents cited that they were of English ancestry, making them the largest group at the time.[42] In the 2000 United States Census, 6.9% of the American population chose to self-identify itself as having "American ancestry."[2] The four states in which a plurality of the population reported American ancestry were Arkansas (15.7%), Kentucky (20.7%), Tennessee (17.3%), and West Virginia (18.7%).[40] Sizable percentages of the populations of Alabama (16.8%), Mississippi (14.0%), North Carolina (13.7%), South Carolina (13.7%), Georgia (13.3%), and Indiana (11.8%) also reported American ancestry.[43]  In the Southern United States as a whole, 11.2% reported "American" ancestry, second only to African American. American was the fourth most common ancestry reported in the Midwest (6.5%) and West (4.1%). All Southern states except for Delaware, Maryland, Florida, and Texas reported 10% or more American, but outside the South, only Missouri and Indiana did so. American was one of the top five ancestries reported in all Southern states except for Delaware, in four Midwestern states bordering the South (Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, and Ohio) as well as Iowa, and in six Northwestern states (Colorado, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming), but only one Northeastern state, Maine. The pattern of areas with high levels of American is similar to that of areas with high levels of not reporting any national ancestry.[43] In the 2014 American Community Survey, German Americans (14.4%), Irish Americans (10.4%), English Americans (7.6%), and Italian Americans (5.4%) were the four largest self-reported European ancestry groups in the United States, forming 37.8% of the total population.[44] However, English, Scotch-Irish, and English American demography is considered to be seriously undercounted, as the 6.9% of U.S. Census respondents who self-report and identify simply as "American" are primarily of these ancestries.[9][10] Academic analysisReynolds Farley writes that "we may now be in an era of optional ethnicity, in which no simple census question will distinguish those who identify strongly with a specific European group from those who report symbolic or imagined ethnicity."[37] Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters write "As whites become increasingly distant in generations and time from their immigrant ancestors, the tendency to distort, or remember selectively, one's ethnic origins increases.... [E]thnic categories are social phenomena that over the long run are constantly being redefined and reformulated."[39][45] Mary C. Waters contends that white Americans of European origin are afforded a wide range of choice: "In a sense, they are constantly given an actual choice—they can either identify themselves with their ethnic ancestry or they can 'melt' into the wider society and call themselves American."[46] Professors Anthony Daniel Perez and Charles Hirschman write "European national origins are still common among whites—almost 3 of 5 whites name one or more European countries in response to the ancestry question. ... However, a significant share of whites respond that they are simply "American" or leave the ancestry question blank on their census forms. Ethnicity is receding from the consciousness of many white Americans. Because national origins do not count for very much in contemporary America, many whites are content with a simplified Americanized racial identity. The loss of specific ancestral attachments among many white Americans also results from high patterns of intermarriage and ethnic blending among whites of different European stocks."[8] The response of American ancestry is addressed by the United States Census Bureau as follows:

GeneticsA 2015 genetic study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics analyzed the genetic ancestry of 148,789 European Americans. The study concluded that Inferred English/Irish ancestry is found in European Americans from all states at mean proportions of more than 20% and represents a majority of ancestry (more than 50% mean proportion) in states such as Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee. These states are similarly highlighted in the map of the self-reported "American" ethnicity in the US Census survey, which might reflect regions with lower subsequent migration from other parts of Europe.[48] See also

ReferencesCitations

Sources

|

||||||||||||||||||||