|

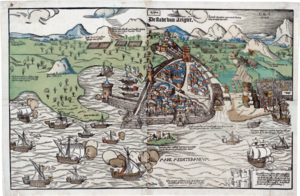

Algiers expedition (1541)

The 1541 Algiers expedition occurred when Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire and king of Spain attempted to lead an amphibious attack against the Regency of Algiers. Inadequate planning, particularly against unfavourable weather, led to the failure of the expedition. BackgroundAlgiers had been under the control of the Ottoman emperor Suleiman the Magnificent since its help in 1529 by Hayreddin Barbarossa. Barbarossa had left Algiers in 1535 to be named High Admiral of the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople, and was replaced as governor by Hasan Agha, a Sardinian eunuch and renegade.[3] Hassan had in his service the well-known Ottoman naval commanders Dragut, Sālih Reïs, and Sinān Pasha.[3] Charles V made considerable preparations for the expedition, wishing to obtain revenge for the recent siege of Buda.[9] However, the Spanish and Genoese fleets were severely damaged by a storm, forcing him to abandon the venture.[10][11] ExpeditionCharles V embarked very late in the season, on 28 September 1541, delayed by troubles in Germany and Flanders.[3][12] The fleet was assembled in the Bay of Palma, at Majorca.[3] It had more than 500 sails and 24,000 soldiers.[3] A fleet led by Andrea Doria was dispatched with the help of allied nations including the Republic of Genoa, the Kingdom of Naples, and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem to transport the troops from Spain and the Netherlands.[13] After enduring difficult weather, the fleet only arrived in front of Algiers on 19 October as a storm formed.[14] Distinguished Spanish commanders accompanied Charles V on this expedition, including Hernán Cortés, the conqueror of Mexico, though he was never invited to the War Council.[12] Troops were disembarked on 23 October, and Charles established his headquarters on a land promontory surrounded by German troops.[12] German, Spanish, and Italian troops, accompanied by 150 Knights of Malta, began to land while repelling Algerine opposition, soon surrounding the city, except for the northern part.[3] Hayreddin's deputy Hassan Agha had a strong defence at the gate of Bab Azzoun and caused serious casualties among the Maltese knights.[15] The fate of the city seemed to be sealed; however, the following day the weather became severe, with heavy rain. Many galleys lost their anchors, and 15 were wrecked onshore. Another 33 carracks sank, while many more were dispersed.[16] As more troops attempted to land, the Algerines started to make sorties, attacking the newly arrived. Charles V was surrounded, and only saved by the resistance of the Knights Hospitaller.[17]  Andrea Doria managed to find a safer harbour for the remainder of the fleet at Cape Matifu, five miles east of Algiers. He enjoined Charles V to abandon his position and join him in Matifu, which Charles V did with great difficulty.[18] From there, still oppressed by the weather, the remaining troops sailed to Béjaïa, still a Spanish harbour at that time. Charles could not depart for the open sea until 23 November.[19] Throwing his horses and crown overboard, Charles abandoned his army and sailed home.[20] He finally reached Cartagena, in southeast Spain, on 3 December.[21]  Losses amongst the invading force were heavy with 150 ships lost and large numbers of sailors and soldiers.[3] A Turkish chronicler wrote that the Berber tribes massacred 12,000 invaders.[22] Leaving war materiel, including 100 to 200 guns which were recovered for the ramparts of Algiers, Charles' army was taken prisoner in such numbers that it was said the markets of Algiers were filled with slaves; so much that in 1541, it was said they were being sold for an onion per head.[23] Hasan Agha was rewarded with the title of Beylerbey for his exploits over the Christian forces.[24] ChronologyThe chronology of the expedition reconstructed by Daniel Nordman.[25]

AftermathThe disaster considerably weakened the Spanish, and Hassan Agha took the opportunity to attack Mers-el-Kebir, the harbour of the Spanish base of Oran, in July 1542.[26] Charles Lamb suggests that this storm may have influenced Shakespeare's character, the sea witch Sycorax in The Tempest. Sycorax, an Algerian sorceress, was banished from her homeland for wreaking havoc with her witchcraft, but was spared execution "for one thing she did". This elusive "one thing" is never stated; however Charles Lamb suggests that Shakespeare drew upon the legend of an unnamed Algerian witch who summoned a ferocious tempest which destroyed the 1541 invasion fleet, and it was this act of defending her nation which prevented her people from executing her.   See alsoNotes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||