|

Acacia mearnsii

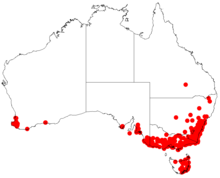

Acacia mearnsii, commonly known as black wattle, late black wattle or green wattle,[2] is a species of flowering plant in the family Fabaceae and is endemic to south-eastern Australia. It is usually an erect tree with smooth bark, bipinnate leaves and spherical heads of fragrant pale yellow or cream-coloured flowers followed by black to reddish brown pods. In some other parts of the world, it is regarded as an invasive species. DescriptionAcacis mearnsii is a spreading shrub or erect tree that typically grows to a height of 10 m (33 ft) and has smooth bark, sometimes corrugated at the base of old specimens. The leaves are bipinnate with 7 to 31 pairs of pinnae, each with 25 to 78 pairs of pinnules. There is a spherical gland up to 8 mm (0.31 in) below the lowest pair of pinnae. The scented flowers are arranged in spherical heads of 20 to 40, pale yellow or cream-coloured, with the heads on hairy peduncles 2–8 mm (0.08–0.31 in) long. Flowering mainly occurs from October to December and black to reddish-brown pods, 30–150 mm (1.2–5.9 in) long and 4.5–8 mm (0.18–0.31 in) wide develop from October to February.[2][3][4] TaxonomyBelgian naturalist Émile Auguste Joseph De Wildeman described the black wattle in 1925 in his book Plantae Bequaertianae.[5] The species is named after American naturalist Edgar Alexander Mearns, who collected the type from a cultivated specimen in East Africa.[6] Along with other bipinnate wattles, it is classified in the section Botrycephalae within the subgenus Phyllodineae in the genus Acacia. An analysis of genomic and chloroplast DNA along with morphological characters found that the section is polyphyletic, though the close relationships of many species were unable to be resolved. Acacia mearnsii appears to be most closely related to A. dealbata, A. nanodealbata and A. baileyana.[7] Distribution and habitatA. mearnsii is native to south-eastern Australia and Tasmania, but has been introduced to North America, South America, Asia, Europe, Pacific and Indian Ocean islands, Africa, and New Zealand.[8][9][10][11][12] In these areas it is often used as a commercial source of tannin or a source of firewood for local communities. In some regions, introduced plants of this species are considered a weed. This is because they threaten native habitats by competing with indigenous vegetation, replacing grass communities, reducing native biodiversity and increasing water loss from riparian zones. In Africa, A. mearnsii competes with local vegetation for nitrogen and water resources, which are particularly scarce in certain regions, endangering the livelihoods of millions of people.[13] In its native range A. mearnsii is a tree of tall woodland and forests in subtropical and warm temperate regions. In Africa the species grows in disturbed areas, range/grasslands, riparian zones, urban areas, water courses, and mesic habitats at an altitude of between 600 and 1,700 metres (2,000 and 5,600 ft). In Africa it grows in a range of climates including warm temperate dry climates and moist tropical climates. A. mearnsii is reported to tolerate an annual precipitation of between 66 and 228 cm (26 and 90 in), an annual mean temperature of 14.7 to 27.8 °C (58.5 to 82.0 °F), and a pH of 5.0–7.2.[14] A. mearnsii does not grow well on very dry and poor soils.[15] Ecology in AustraliaA. mearnsii plays an important role in the native ecosystem of Australia. As a pioneer plant it quickly binds the erosion-prone soil following the bushfires that are common in its Australian habitats. Like other leguminous plants, it fixes atmospheric nitrogen in the soil. Other woodland species can rapidly use these increased nitrogen levels provided by the nodules of bacteria present in their expansive root systems. Hence they play a critical part in the natural regeneration of Australian bushland after fires.

Mycorrhizal fungi attach to the roots to produce food for marsupial animals, and these animals in turn disperse the spores in their droppings to perpetuate the symbiotic relationship between the wattle's roots and mycorrhizal fungi. The cracks and crevices in the wattle's bark are home for many insects and invertebrates. The rare Tasmanian hairstreak butterfly lays her eggs in these cracks, which hatch to produce caterpillar larva attended by ants (Iridomyrmex sp.) that feed off the sweet exudates from the larva.[citation needed] A. mearnsii is used similarly as a larval host plant and food source by the imperial hairstreak, Jalmenus evagoras.[20] The tree is home to various grubs, such as wood moths, which provide a food source to black cockatoos, which strip the bark for access to these borers. During winter insects, birds and marsupials are hosted by the black wattle with the aid of their supplies of nectar in their leaf axials. These creatures provide an important predatory role to deal with tree dieback caused by scarab beetles and pasture pests. Black wattles, along with gums, native box and native hop form the framework vegetation on so-called "hill-topping" sites. They are often constitute isolated remnant pockets of native vegetation amongst a lower sea of exotic pasture. These "hill-topping" sites are critical habitat for male butterflies to attract females for mating, which then lay their eggs under the wattle's bark elsewhere but still within close proximity. It's the only acceptable mating site in the area for these butterflies. Black wattle flowers provide very nitrogen-rich pollen with no nectar. They attract pollen-feeding birds, such as wattlebirds, yellow-throated honeyeaters and New Holland honeyeaters. The protein-rich nectar in the leaf axials is very sustaining for nurturing the growth of juvenile nestlings and young invertebrates, e.g. ants. Ants harvest the seed, attracted by the fleshy, oil-rich elaiosome (or seed stalk), which they bury and store in widely dispersed locations. These seeds are buried ready for germinating with the next soaking rains. However, a "wattle seed-eating insect" which enjoys liquid meals using its proboscis-like injector to pierce the testa and suck out the embryo, often reduces the seed's viability.[21] Status as an invasive speciesIn some parts of the world, A. mearnsii is considered to be an invasive species. Its invasiveness is due to its production of large numbers of seeds each year and to its large crown that shades other species.[22] In South Africa it is listed as a Category 2 invader in the National Environmental Biodiversity Management Act. This means a permit is required to handle a species and ensure it does not spread beyond the area of the permit.[23] UsesThe Ngunnawal people of the Australian Capital Territory use the gum as food and to make cement (when mixed with ash), and to ensure a supply of sap, the bark was cut in the autumn.[24] The bark was also used to make coarse rope and string, and used to be infused in water to make a medicine for indigestion.[24] ReproductionA. mearnsii produces copious numbers of small seeds that are not dispersed actively. The species may resprout from basal shoots following a fire.[8] It also generates numerous suckers that result in thickets consisting of clones.[8] Seeds may remain viable for up to 50 years.[25] ChemistryLeuco-fisetinidin, a flavan-3,4-diol (leucoanthocyanidin) and a monomer of the condensed tannins called profisetinidins, can be extracted from the heartwood of A. mearnsii.[26] References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Acacia mearnsii. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||