|

1951 24 Hours of Le Mans

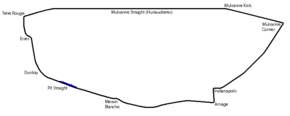

The 1951 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 19th Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 23 and 24 June 1951. It was won by Peter Walker and Peter Whitehead in their works-entered Jaguar C-type, the first Le Mans win for the marque. The arrival of Jaguar's and Cunningham's first purpose-built racers in direct competition with Ferrari, and the first showing for Porsche and Lancia, marked the beginning of an era of intense competition between manufacturers of sports cars. The more powerful new sport racers would develop rapidly and put a final end to luxury touring cars and their derivatives as top contenders at Le Mans. It was the final outing for Delahaye and Bentley (for 50 years) and the sports prototype tide would overwhelm Talbot-Lago in the next couple of years. The race was marred by the death of French driver Jean Larivière within the opening laps of the race. RegulationsThis year there were no significant changes to the regulations, by either the CSI or the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO), except to create a Reserve list as a back-up to the basic sixty entrants. Entries Works entries were entered by Aston Martin, Frazer-Nash, Healey, Jaguar, Jowett, Panhard and Renault as well as self-built cars from Allard, Cunningham, DB, Delettrez, Gordini and Monopole. The biggest sensation were the three works cars from Jaguar after their private entry the year before. Designed in complete secrecy specifically for Le Mans, the XK-120C, or C-Type (‘C’ standing for ‘Competition’) was 450 kg lighter than before and its 3.4L engine developed 205 bhp with a top speed of 160 mph (257 km/h).[1] Along with Fairman, Whitehead and Johnson, team manager “Lofty” England paired them up respectively with debutants Stirling Moss and Peter Whitehead and multiple Mille Miglia winner Clemente Biondetti. Sydney Allard again had the biggest cars, returning with a pair of his J2s with their 5.4L Cadillac engines.[2] John Wyer’s works Aston Martin team fielded three DB2 coupés, bolstered by a pair of privately-entered DB-2s. In the 3.0L class, their reliable 2.6L engines had improved to develop 138bhp.[3]   Briggs Cunningham also returned, this year with three cars of his own design – the first serious American entry for victory in 20 years. Although heavy, the C-2R with its big 5.4L Chrysler V8 engine, could develop a powerful 225bhp and had a top speed over 240 km/h. Defending French honour, after the previous year’s victory, were six private-entrant Talbots, including four of the two-seat Formula 1 conversions. With works backing, 'Tony' Lago hired the top Argentinian drivers from F1: Juan-Manuel Fangio drove with last year’s winner Louis Rosier, while José Froilán González was paired with the young Onofre Marimón.[4] This year also marked the final entry by Delahaye. The biggest entry from a single marque were nine Ferraris (including three entered by US Ferrari-agent & triple Le Mans winner Luigi Chinetti). Although there was still no works team, they did include four of the exciting new ‘340 America’ in the big-engine class.[2] After winning the Mille Miglia, they arrived as one of the pre-race favourites: the 4.1L V12 engine (based on the F1 4.5L engine) matched the Cunninghams, producing 230 bhp and a top speed around 240 km/h. There were also three new ‘212 Export’ models with 2.4L engines and a pair of the older 2.0L, race-proven, ‘166MM’ models. The other Italian entry was a lone Lancia, here for the first time.[2] Vittorio Jano’s Aurelia B20 design was a development of the B10, the first production car with a V6 engine. Entered by the Milanese Scuderia Ambrosiana team of Count Giovanni Lurani, it was the first car at Le Mans to race with radial tyres.[5] Finally, both the Bentley sedan and Delettrez diesel returned for the last time.[2] In the smaller categories, there was a significant new entrant: Race director and founder Charles Faroux had approached Porsche to be the first German car in the post-war races.[2] Five of its modern new 356 SL (Super Leicht) model were built but two were wrecked in road-testing, but two did make the entry-list.[6] Its 1086cc engine developed just 46bhp but that still gave a top speed of 100mph (160 km/h).[7] Again, French makes dominated the small classes, with 16 entries from Panhard, DB, Monopole, Renault, Simca, Gordini and several one-off specials (all with an assortment of Panhard, Simca or Renault engines)[2] Up against them, aside from the Porsches, was a single Czech Aero-Minor, a pair of Jowetts, an MG and a new American Crosley. PracticeThe Jaguars immediately showed their pace, although Peter Walker complained that the lights were insufficient in the night-practice. When it was pointed out he had his tinted glasses on, he took them off and went out and immediately did an unofficial lap of 4:46. But it was Phil Walters’ Cunningham that set the fastest official practice lap at 5:03.[8][9] The later practice sessions were compromised by very wet weather. Rudolf Sauerwein suffered severe leg injuries when his new Porsche crashed and rolled, almost collecting Moss's Jaguar and Morris-Goodall's Aston Martin following close behind.[7] A number of cars had engine problems in practice that were traced to the fuel supplied by the ACO – nominally 80-octane, but that was suspect. Many teams needed to do last minute engine modifications.[10] Race StartAfter all the rain in practice, race-day also started wet but it was dry for the start. Tom Cole's Allard was first away, but at the end of the first lap, it was the Talbot of González ahead of Moss and Cole. After three laps the young, very fast, Stirling Moss dashed into the lead and took on the role that was to become his signature - the hare sent out to break the pursuing hounds, running to an assigned pace.[2] However tragedy struck on the sixth lap: French driver Jean Larivière crashed his Ferrari 212 heavily into a sandbank at Tertre Rouge, getting airborne. He was killed instantly when virtually decapitated by a wire fence.[11][12] [Notes 1] The race continued though, and Moss set a blistering pace, repeatedly lowering Rosier's 1950 lap record (eventually, over 6 seconds quicker). After an hour, Moss led González, ahead of the Jaguars of Biondetti and Walker, then the Talbots of Chaboud and Rosier. By the end of the second hour, Moss had put a lap on the whole field. At the four-hour mark Moss & Fairman had a lead of over 2 laps, with the Jaguar team running 1-2-3, ahead of the Talbots of González and Fangio. Soon afterward, the rain returned and stayed for the rest of the night. The pace was starting to take its toll: Both Allards had gone off track, and repairing the damage put them well down. Chaboud's Talbot was out with radiator problems, and a loss of oil pressure caused a similar problem stopping the Biondetti Jaguar. Louis Chiron, running in the top 10, ran his Ferrari out of gas on-track, but when the officials found out a mechanic had driven out to him with a tank of fuel to top up he was disqualified.[13] In the smaller classes, the 1500cc Gordinis were comfortably ahead of their English competition (the Jowetts and MG) – at times 40 seconds a lap faster[14] - Manzon and Trintignant running as high as 15th and 16th respectively, mixing it with the bigger cars until both were put out with engine problems after only 4 hours. NightJust before midnight, after his car had held the lead for more than 7 hours, Moss’ impressive run came to an end – a conrod broke due, like Biondetti, due to a major loss of oil pressure. Soon after, Rosier was stopped by a split oil tank. The remaining works Jaguar of Walker/Whitehead inherited the lead, a lap ahead of González/Marimón. The Britons extended the lead to 7 laps, easily matching the Talbot's pace through the night until the latter car retired with a blown head gasket at the halfway mark.[15] The Ferrari challenge never really materialised, although wealthy Englishman Eddie Hall, who had driven solo the previous year to 2nd place, had his Ferrari 340 up to as high as 3rd during the night. The big heavy Cunninghams suffered in the greasy wet conditions; two had been held up in the first couple of hours and were well down the order. Huntoon, co-driving the boss’ car, slid off at Indianapolis wrecking the steering, then soon afterward Rand spun his car in traffic at the Dunlop curve. He missed the other cars but slammed into the roadside bank. The third car though, of Fitch/Walters, had been in the top 10 throughout, steadily picking up places as others fell out, and was up to 2nd when the Talbot retired. The Allard/Cole car had charged through the field up to 4th after its initial delay, but was finally stopped at the end of the night by a broken gearbox. Back in the junior classes, with only the reserve-entry Jowett left, the Gordinis were making good progress, with a 9-lap lead, when disaster struck – both remaining Gordinis were retired late in the night with yet more engine problems. MorningAs dawn broke, the Jaguar had a comfortable 8-lap lead over the Cunningham, the Macklin/Thompson Aston Martin and the Rolt/Hamilton Nash-Healey. Hall's Ferrari gave up with a flat battery and would not restart. The two Talbots of Mairesse/Meyrat and Bouillin/Marchand followed, trying to stage a fightback, split by the Abecassis/Shawe-Taylor Aston Martin. This order stayed fairly constant through the morning, until midday when the Cunningham hit the pits with engine problems. The crew made repairs and it crawled around doing occasional slow laps, waiting for the race-end. By pushing hard, Mairesse and Meyrat picked off the Nash-Healey in the early morning, then passed the Aston Martin into 3rd about 11am, which became 2nd when the Cunningham stopped. Meanwhile, even being the sole survivor of the S1500 class, it still took the Jowett over an hour to overtake the leading Gordini on distance – they eventually cruised home to finish 21st.[16] Finish and post-raceIn the end, the Jaguar won at a canter, with a 9-lap lead over the Talbot. Despite 16 hours of rain, the Jaguar easily broke the distance record, covering over 3600 km. Even though Mairesse put in his fastest lap in the last hour, and they covered two more laps than Rosier's winning Talbot last year, Meyrat and Mairesse were not going to catch the Jaguar and they again finished second. Debutants Pierre Bouillin (racing under the pseudonym Levegh) and René Marchand, driving Mairesse's 1949-race Talbot finished a creditable 4th. The Aston Martins again proved extremely reliable: five entered, five finished with the three works cars coming in 3rd, 5th and 7th and 1-2-3 in class. Macklin & Thompson in 3rd were less than a lap behind the Talbot, having spent only 10 minutes in the pits during the whole race.[11] Like the previous year, the Anglo-American Nash-Healey of Rolt/Hamilton had proven very reliable. Even with its bigger engine, its heavier weight meant it could never compete with the Jaguars and Talbots in its class for pace, but that reliability had got it up to 4th in the morning, until overtaken by the Talbot and the leading Aston Martin and finishing 6th.[17] Only one of the big Ferraris finished – Chinetti's own, in 8th, although three of the smaller ones did make it to the end. The Lancia had run like clockwork finishing 12th. Incredibly it had covered nearly 2000 miles on just a single set of tyres, and was then driven back to Turin after the race.[5]   After the tribulations getting to the start, the new Porsche of Auguste Veuillet (the Porsche agent in Paris[7]) won its class at first attempt; a promising start to an exceptional association with Le Mans. For the second year running the Biennial Cup and the Index of Performance both went to the works Monopole by Pierre Hérnard & Jean de Montrémy[18][19] Despite their best attempts, neither Fitch's Cunningham, the second Allard nor the Bentley were classified – the former two could not get their final laps done in the minimum time and the latter missed its minimum required distance by just 4 miles (half a lap!).[20] The popular American adage of the time – “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” – was particularly apt for Jaguar. It was later estimated that extra sales of US$12 million were generated in the USA alone from their Le Mans win.[9] By contrast, the negative press for Gordini's failure led to Simca withdrawing its engine supply to the team.[14] Official results

Did not finish

Did not start

17th Rudge-Whitworth Biennial Cup (1950/1951)

Statistics

Trophy Winners

Notes

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||