|

164th Rifle Division

The 164th Rifle Division was originally formed as an infantry division of the Red Army in the Byelorussian Military District, based on the shtat (table of organization and equipment) of the previous September. In January 1940 it was moved north during the Winter War with Finland, but saw limited combat there. At the start of the German invasion in June 1941 it was in 17th Rifle Corps of 12th Army of the Kiev Special Military District in the Carpathian Mountains along the border with Romania, and so avoided the armored thrusts of Army Group South. Nevertheless, it was forced to retreat in early July as Soviet forces to the north and south fell back or were overrun. Now part of 18th Army of Southern Front the 164th fell back through southern Ukraine into October, when it was finally caught by panzers on the open steppe and scattered. It was effectively destroyed by October 30, but officially remained on the books until nearly the end of December. A new 164th was created in January 1942 in the Ural Military District based on a 400-series division that began forming the previous month. After forming up until April it was sent west by rail where it was eventually assigned to the 31st Army of Western Front just prior to the summer offensive against the Rzhev salient. During the offensive the division was part of the force that liberated Zubtsov, but was halted before the outskirts of Rzhev. In October the division was moved to 49th Army, and in the spring of 1943 played a limited role in the pursuit of the German forces from the salient. In August it was part of 33rd Army and took a leading role in the grinding battles that eventually liberated Smolensk in September. As the offensive continued the 164th ran up against the German defenses east of Orsha, and it spent several months in heavy fighting along that axis with limited success. Over the winter the 164th was moved, with its Army, somewhat to the north, where it took part in equally frustrating battles attempting to encircle Vitebsk. Western Front was disbanded in April 1944, and the division was reassigned to 39th Army, beginning the summer offensive in 1st Baltic Front. It played a leading role in the final fighting for that city and received its name as a battle honor. With the German front torn open the Front pursued into the "Baltic Gap" through Lithuania during July, and the 164th was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for its part in the liberation of Kaunas. In the following weeks it faced a German counteroffensive near Raseiniai before moving north toward Riga as part of 4th Shock Army. Once this city was taken in mid-October the division was one of many assigned to contain the remainder of Army Group North trapped in the Courland Pocket, and it remained in western Latvia for the duration under several army commands but finally back in 4th Shock. Postwar, it was moved to the South Urals where it was converted to a rifle brigade in 1946. 1st FormationThe division first began forming in November 1939, at Orsha in the Byelorussian Military District. Its commander, Sergei Ivanovich Denisov, was promoted to the rank of Kombrig on November 4; he had previously led the 20th Mechanized Brigade. On November 27, while barely formed, the division entrained for Petrozavodsk where it arrived a month later. The Winter War with Finland had begun on November 30, and on January 12, 1940, it was assigned to 1st Rifle Corps in 8th Army. In the first days of March the 164th was included in a force that was to operate against a Finnish grouping in the Loimola area. During this operation Lt. Aleksandr Antonovich Rozka, a member of the Komsomol, distinguished himself sufficiently to become a Hero of the Soviet Union. A platoon commander in the 230th Antitank Battalion, on March 9 he led a group of his men in an attack on a fortified height which led to the capture of two heavy and five light machine guns, plus 40 rifles. He was awarded his Gold Star on May 19, and went on to serve in the defense of Leningrad, eventually reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel before his retirement in 1955. He lived and worked in Kamianets-Podilskyi until his death on January 31, 1970, at the age of 54.[1] The war ended on March 13, before the division saw much more action. In April it was again loaded up and sent south to the Odessa Military District, where it soon took over a sector of the Prut River along the Romanian border. On January 15, 1941 Kombrig Denisov left the division to become an instructor at the Military Academy of Mechanisation and Motorisation. His rank was modernized to major general of tank troops on November 10, 1942, and in the spring of 1943 he was briefly the acting commander of 1st Guards Mechanized Corps, but he was killed in action on June 22. Col. Anatolii Nikolaevich Chervinskii followed him in command of the 164th. Prior to the German invasion the division was assigned to 12th Army's 17th Rifle Corps, which also contained the 60th and 96th Mountain Rifle Divisions.[2] Its order of battle on June 22, 1941, was as follows:

By this time the division's main body was centered to the south of Khotyn.[4] It had 9,930 personnel on strength and was actually over-equipped with 10,444 rifles, 3,621 semi-automatic rifles, 400 submachine guns, 439 light machine guns, 195 heavy machine guns, 58 45mm antitank guns, 38 76mm cannon and guns, 28 122mm and 12 152mm howitzers, 151 mortars of all calibres, 283 trucks, 29 tractors, and 1,921 horses. Its main shortage was motorized transport.[5] Operation BarbarossaLate on June 21 the commander of Kiev Special Military District (soon Southwestern Front), Col. Gen. M. P. Kirponos, began sending orders to his armies to open their "red packets" of wartime instructions even though he had not yet been authorized to do so by the STAVKA. Under these instructions the 17th Corps was to move some 100km across wooded, mountainous terrain to take up positions along the frontier. The chief of staff of 12th Army, Gen. B. Arushnya, spoke to Kirponos by phone around 0400 hours on June 22, reporting that the situation along the Army's sector was "still quiet". An hour later he was contacted by Kirponos' chief of staff:

Once it reached the Prut the 17th Corps was facing elements of the Romanian 3rd Army, which had already attempted to force crossings with no success. On June 25 the division was transferred with its Corps to the 18th Army which was being formed in Southern Front (former Odessa Military District).[7] The 164th would remain under these commands until it was disbanded.[8] Beginning on July 1 the Romanians renewed their efforts to force the river, particularly at the Lipcani-Rădăuți Bridge. Chervinskii had been under orders to preserve the crossing for a planned offensive into Romania, but this turned into a stalemate where machine gun and mortar fire prevented both sides from crossing or destroying it. After taking losses, including two tanks, the Romanian force switched its attention to Novoselitsy, which was held by the 144th Reconnaissance Battalion and included a lodgement on the "Romanian" side of the river. An artillery duel ensued; this ended about 2200 hours after which the scouts reported sounds indicating an attack was imminent. In fact, this was a ruse to cover a crossing attempt by German troops on another sector, but it also failed. The 164th held off all Axis crossing operations until July 5, after finally destroying the bridge, but due to other Soviet forces falling back to the north and south it was forced to retreat to the Dniestr River, which it crossed on the night of July 5/6.[9] By July 7, 17th Corps had taken up positions southwest of Kamianets-Podilskyi, and by four days later it had retreated past that place, now facing the Hungarian VIII Army Corps. As of July 14 the 164th was attempting to hold a sector on the Dniestr on the right flank of 55th Rifle Corps' 169th Rifle Division. By now the 60th Mountain Division had become detached from 17th Corps and rejoined 12th Army;[10] as a result it would be encircled in the Uman Pocket in early August and destroyed. As the retreat continued, elements of this and other divisions of 17th Corps came under Chervinskii's command, including the 651st Mountain Rifle Regiment of 96th Mountain Division.[11] Retreat through south UkraineBy July 27 the 164th was organizing to cross the Southern Bug River in the vicinity of Haivoron. Chervinskii exercised insufficient supervision over the operation, and the bridge was destroyed prematurely, leaving most of the 494th Artillery Regiment (20 cannon, 12 mortars, two tractors, three motor vehicles, and part of the supply train) plus many of the personnel of 651st Mountain Regiment, isolated on the west bank. On October 17 he was replaced by Lt. Col. Vladimir Yakovlevich Vladimirov, and two days later he was tried by a military tribunal of 18th Army, found guilty of negligence, and sentenced to eight years in a labor camp, deferred until the end of military operations. From the end of the month he commanded two rifle regiments of the 51st Rifle Division before being made commander of the 78th Naval Rifle Brigade in February 1942. In June this brigade served as the basis of the new 318th Rifle Division and Chervinskii remained in command, but became missing in action in July during the early stages of the German summer offensive.[12] Southern Front largely escaped the debacle suffered by Southwestern Front east of Kiyv in September and the 164th continued to retreat with 18th Army during this period. Following this victory the OKH ordered Army Group South to attack simultaneously toward Kharkiv, the Donbas, and Rostov-on-Don, with its left wing forces, while the right wing encircled Southern Front and invaded the Crimea. 1st Panzer Army attacked off the march from the Poltava area and soon smashed the defenses of 12th Army before exploiting toward Melitopol, encircling six divisions of the Front's 18th and 6th Armies on October 7. Over the next three days elements of the 18th were able to break out toward Taganrog, pursued by panzers which halted on the Mius River to regroup on October 13.[13] During this fighting the division was effectively overrun and scattered, and Lt. Colonel Vladimirov officially left his command on October 30.[14] However, in common with most divisions of Southwestern and Southern Fronts that were destroyed in this period, the 164th was not finally written off until December 27. 2nd FormationThe 435th Rifle Division began forming in December 1941 until January 4, 1942 at Achit in the Ural Military District. On the latter date it was redesignated as the new 164th Rifle Division.[15] Its order of battle was very similar to that of the 1st formation:

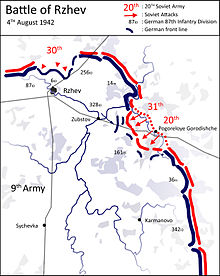

Col. Pyotr Grigorevich Kasperovich was appointed to command on the date of redesignation. The division remained in the Ural District until April, when it began moving west by rail, initially assigned to the 1st Reserve Army in the Reserve of the Supreme High Command, but moving to Western Front's 31st Army in July, just it time to take part in the Front's summer offensive toward Rzhev.[17][18] First Rzhev-Sychyovka Offensive Western Front began its part in this operation on August 4. A powerful artillery preparation reportedly knocked out 80 percent of German weapons, after which the German defenses were penetrated on both sides of Pogoreloe Gorodishche and the 31st Army's mobile group rushed through the breaches towards Zubtsov. By the evening of August 6 the breach in German 9th Army's front had expanded up to 30km wide and up to 25km deep. The following day the STAVKA appointed Army Gen. G. K. Zhukov to coordinate the offensives of Western and Kalinin Fronts; Zhukov proposed to liberate Rzhev with 31st and 30th Armies as soon as August 9. However, heavy German counterattacks, complicated by adverse weather, soon slowed the advance drastically.[19] On August 12 Colonel Kasperovich left the 164th and was replaced a week later by Col. Nikolai Georgievich Tsyganov. Kasperovich would be promoted to the rank of major general of artillery on November 18, 1944, and would end the war as 1st Shock Army's commander of artillery. Tsyganov had previously served as deputy commander of 20th Guards Rifle Division. On August 23 the 31st Army, in concert with elements of the 29th Army, finally liberated Zubtsov. While this date is officially considered the end of the offensive in Soviet sources, in fact bitter fighting continued west of Zubtsov into mid-September. At dawn on September 8, 29th and 31st Armies went on a determined offensive to seize the southern part of Rzhev. Despite resolute attacks through the following day against the German 161st Infantry Division the 31st made little progress. It suspended its attacks temporarily on September 16 but resumed them with three divisions on its right flank on September 21–23 with similar lack of success. Over the course of the fighting from August 4 to September 15 the Army suffered a total of 43,321 total losses in personnel.[20] By the end of September the depleted division had been moved to the Western Front reserves.[21] Into Western RussiaIn October the 164th joined 49th Army, still in Western Front.[22] On January 3, 1943, Colonel Tsyganov left the division and was placed at the disposal of the Front's Military Council, where he remained for a few months before being named as chief of staff of 8th Guards Rifle Corps. He would later lead the 11th Guards Rifle Division and was made a Hero of the Soviet Union on April 19, 1945, eventually rising to the rank of colonel general in 1961. He was replaced by Maj. Gen. Vasilii Andreevich Revyakin, who had most recently led the 1st Guards Motorized Rifle Division. During March the 49th Army played a minor part in the pursuit as 9th Army withdrew from the Rzhev salient (Operation Büffel), before coming up against the fortified positions at its base. In April, as the fighting settled into an extended lull, the 164th was transferred to 33rd Army, which was under command of Lt. Gen. V. N. Gordov and was also in Western Front.[23] The STAVKA chose to stand on the defensive in the Kursk region and absorb the attacks of 9th Army and 4th Panzer Army before going over to the counteroffensive. Western Front prepared for its own offensive in the direction of Smolensk and 33rd Army was substantially reinforced with armor and artillery by the beginning of August.[24] Operation Suvorov Operation Suvorov began on August 7. 33rd Army was still facing the defenses of the Büffel-Stellung east of Spas-Demensk. At this time its divisions averaged 6,500 - 7,000 personnel each (70-75 percent of their authorized strength). Gordov formed his main shock group from the 42nd, 164th and 160th Rifle Divisions and the 256th Tank Brigade but these ran into tough resistance from the 480th Grenadier Regiment of the 260th Infantry Division in the Kurkino sector. Only the 164th achieved a limited success, taking the village of Chotilovka at 2000 hours and threatening to drive a wedge between that German regiment and its neighboring 460th Grenadier Regiment until the 480th threw in its reserve battalion and stopped any further advance. By early afternoon the Front commander, Col. Gen. V. D. Sokolovskii was becoming frustrated about the inability of most his units to advance. The offensive resumed at 0730 hours on August 8 after a 30-minute artillery preparation, and the 164th attacked toward Sluzna in an effort to outflank the defenses on Hill 233.3, and overnight this village was abandoned to avoid encirclement. However the garrison fell back to a new line which blocked every effort of the division to continue the advance.[25] Gordov continued attacking on August 9–10 with the shock group on a very narrow front but was stymied at Laski and Gubino; the intervention of an ersatz German battalion appears to have narrowly prevented a Soviet breakthrough. As both sides weakened the fighting continued into the morning of August 13 when the 42nd Division and the 256th Tanks were the first units of 33rd Army into Spas-Demensk. The 164th continued to advance into the void southwest of the town as German forces fell back to their next line of defense. Sokolovskii was forced to call a temporary halt on August 14 to replenish stocks, especially ammunition.[26] Sokolovskii's revised plan put his Front's main effort in the center with the 21st, 33rd, 68th and 10th Guards Armies attacking the German XII Army Corps all along its front until it shattered, then push mobile groups through the gaps to liberate Yelnya. Virtually all the units on both sides were now well below authorized strength and Suvorov was becoming an endurance contest. Ammunition and fuel were still short on the Soviet side given the competing demands of other fronts.[27] By August 19 the 164th had made a penetration on a front from Sobeli to Snopot. Sokolovskii's headquarters ordered the 8th Guards Cavalry Division, supported by self-propelled guns of the 142nd Regiment, into the gap to take the latter place and exploit toward Yelnya. In the course of this fighting the headquarters of the 8th Guards was struck by an aerial bomb and its commander, Maj. Gen. M. I. Surzhikov, was killed.[28] At 0800 hours on August 28 the Western Front began a 90-minute artillery preparation across a 25km-wide front southeast of Yelnya in the sectors of the 10th Guards, 21st and 33rd Armies. Instead of the obvious axis of advance straight up the railway to the city Sokolovskii decided to make his main effort in the 33rd Army sector near Novaya Berezovka. This assault struck the 20th Panzergrenadier Division directly, forcing it backward and away from its junction with the right flank of IX Army Corps. As soon as a gap was forced General Gordov committed the 5th Mechanized Corps at Koshelevo which began to shove wrecked German battlegroups out of its path. Overall the Army managed to advance as much as 8km during the day. On August 29 the 5th Mechanized completed its breakthrough and Gordov was able to add the 6th Guards Cavalry Corps to the exploitation force. By 1330 hours on August 30 it became clear to the German command that Yelnya could not be held and orders for its evacuation were issued within minutes; the city was in Red Army hands by 1900. From here it was only 75km to Smolensk. However, German 4th Army was able to establish a tenuous new front by September 3 and although Sokolovskii continued local attacks through the rest of the week his Front was again brought to a halt by logistical shortages.[29] Liberation of SmolenskThe offensive was renewed at 0545 hours on September 15 with another 90-minute artillery preparation is support of the 68th, 10th Guards, 21st and 33rd Armies against the positions of IX Corps west of Yelnya. This Corps was attempting to hold a 40km-wide front with five decimated divisions. The 78th Assault Division buckled under the onslaught, but the Soviet armies gained 3km at the most, instead of a clear penetration. Nevertheless, at 1600 on September 16 the IX Corps was ordered to fall back to the next defense line. Sokolovskii now directed the 21st and 33rd Armies to pivot to the southwest to cut the Smolensk–Roslavl railway near Pochinok. On the morning of September 25 Smolensk was liberated. During the following days the 33rd Army pushed on toward Mogilev.[30] Orsha OffensivesAs of October 1 the 33rd Army was still facing the depleted 78th Assault and 252nd Infantry Divisions of IX Corps roughly halfway between the Sozh and Dniepr Rivers. For the new attack set for October 3 the 164th was initially held in reserve. Meanwhile the two German divisions had been reassigned to XX Army Corps, joining the 95th and 342nd Infantry Divisions. This provided a stronger defense than was faced by most of Western Front's armies, and the Army's assaults expired by October 9 without achieving any success.[31] Following a substantial regrouping which saw the Army moving north to positions near Lenino that had been occupied by 21st Army, Gordov deployed his 42nd and 290th Rifle and 1st Polish Infantry Divisions in first echelon, with 222nd and 164th Divisions in second echelon, to assault German positions across the Myareya River just north of Lenino. The offensive began early on October 12 following an 85-minute artillery preparation which failed to take the defenders by surprise. In two days of fighting the Western Front armies were almost completely stymied; the Polish Division was able to carve out a wedge up to 3km deep west of Lenino at considerable cost, especially due to air attacks. When the offensive ended on October 18 it had cost the Poles nearly 3,000 casualties and 33rd Army's remaining divisions a further 1,700 personnel, although the 164th largely escaped the carnage as it was not actively engaged.[32] Sokolovskii planned for another offensive on Orsha to begin on November 14. Two shock groups were prepared, with the southern group consisting of elements of 5th And 33rd Armies south of the Dniepr on a 12km-wide sector. It would be supported with an artillery and air preparation of 3-and-a-half hours duration as well as significant strength in armor. At this time the Front's rifle divisions averaged about 4,500 men each. The 164th was assigned to 65th Rifle Corps, still in 33rd Army, before the start of the offensive; the Corps was deployed between Volkolakovka and Rusany with the 164th in second echelon. The 42nd and 222nd Divisions made limited progress in the direction of Guraki but the remainder of the Army's first echelon divisions faltered in the face of withering artillery and machine gun fire. The following day Gordov committed the 153rd and 164th Divisions in repeated attacks against the positions of 18th Panzergrenadier Division in Guraki, to no avail. Only by releasing the 144th Division to battle on November 17 was his Army able to secure a 10km-wide and 3-4km deep bridgehead on the west bank of the Rossasenka River by the end of the next day, at which point the offensive collapsed from exhaustion. The entire effort, which was most successful on 33rd Army's sector, cost Western Front's four attacking armies 38,756 casualties. In preparation for a fifth offensive on Orsha Gordov shifted additional forces into the Rossasenka bridgehead, and in the attack which began on November 30 his divisions, in cooperation with 5th Army, managed to force the defenders back roughly 4km before the lines stabilized. Sokolovskii ordered the Front over to the defense on December 5.[33] Battles for VitebskShortly after this 33rd Army was directed to redeploy substantially to the north to reinforce the left wing of 1st Baltic Front as it attempted to encircle and liberate the city of Vitebsk. When the redeployment and regrouping were completed on December 22 the Army had 13 rifle divisions on strength, supported by one tank corps, four tank brigades, and ten tank and self-propelled artillery regiments, plus substantial artillery. The attack began the following day in cooperation with 39th Army. 65th Corps was deployed north of Khotemle against the 246th Infantry Division with the 23rd Guards Tank Brigade in support. The shock groups forced the defenders back about 1,000 metres on the first day but the commitment of second echelon divisions on December 24 enlarged the penetration to a depth of 2-3km. Despite the arrival of a battlegroup of Feldherrnhalle Panzergrenadier Division on December 25 the entire 33rd Army burst forward from 2-7km, reaching to within 20km of Vitebsk's city center. 33rd Army suffered 33,500 personnel killed, wounded or missing, plus the loss of 34 mortars and 67 guns, in fighting that continued until January 6, 1944.[34] Before the end of December the 164th had been transferred to the Army's 69th Rifle Corps.[35] On New Year's Day General Revyakin left the division to take command of 65th Corps, but he was soon made the STAVKA representative to 1st Belorussian Front. During 1945-46 he would play a leading role in the repatriation of Soviet citizens from Germany. He was replaced for most of January by Col. Grigorii Ivanovich Sinitsyn, who in turn was succeeded for a day by Lt. Col. Fyodor Fyodorovich Erokhin. Col. Semyon Ipatevich Stanovskii took over from January 30 to February 10, but he was replaced the next day by Sinitsyn, who would remain into the postwar. Third Vitebsk OffensiveThe offensive was renewed on January 8. 36th Rifle Corps was the Army's main shock group while Gordov retained the 69th Corps, which also contained the 144th Rifle Division, as his reserve. In the event 69th Corps was not committed. The attack made very little progress and the effort was suspended on January 14. By now the rifle divisions in 33rd Army numbered 2,500 to 3,500 men each, rifle regiments consisted of one or two battalions, battalions of one or two companies, and companies, 18 to 25 men each. Later in the month the 164th returned to 65th Corps.[36] When the offensive was renewed again on February 3 the 65th Corps was part of the Army's shock group, assigned to continue the drive to encircle Vitebsk from the south, although now aiming for a far shallower envelopment. The Corps was deployed in the sector between Vaskova and the Vitebsk–Orsha railway with the 164th in first echelon and the 274th Rifle Division behind, facing the 131st Infantry Division. The artillery preparation was again hindered by ammunition shortages but despite this the 164th penetrated to a depth of 1.5km and seized the strongpoints of Baryshino and Semyonovka on the railroad, 10-11km south of Vitebsk. Gordov ordered his corps commanders to commit their second echelon divisions the next day, but the Luchesa River, only partly frozen and with deep, steep banks, proved a formidable obstacle. The 274th took another strongpoint at Pavliuki in cooperation with 69th Corps, but this was not sufficient progress to justify the commitment of 5th Guards Rifle Corps. On February 8 Gordov ordered Revyakin to move his Corps to new positions west of the railway in order to attack northwest toward and across the Luchesa in tandem with two divisions of 81st Rifle Corps. The objective was to take the German bridgehead at Noviki. In three days of fighting the combined force pushed forward and on February 11 managed to cross the Luchesa northwest of Starintsy and took a bridgehead of its own at Mikhailovo. After repelling several counterattacks by battlegroups of 14th and 95th Infantry Divisions the 164th and 95th Rifle Divisions were able to carve out a 2km-deep lodgement based on Mikhailovo, just east of Porotkovo. Although Sokolovskii and Gordov insisted that the 33rd continue its attacks, all efforts from February 13 on proved futile as its forces were simply too weak. The 164th was left to hold the bridgehead, now under direct Army command and facing the 197th Infantry Division.[37] Fourth and Fifth Vitebsk OffensivesA renewed offensive was planned to begin on February 29 and in preparation Gordov carried out yet another regrouping. His shock grouping consisted of all three of his rifle corps attacking along the Luchesa. The 164th was on its right flank and, in the event of success, was to advance out of its bridgehead in cooperation with 95th Division to the northwest through Rogi to provide flank protection. Before it could begin the commander of the 3rd Panzer Army, Col. Gen. G.-H. Reinhardt, disrupted the plan by shortening his defensive line around the city. The STAVKA took this as a preliminary to a full withdrawal from the Vitebsk salient, and ordered a pursuit. The 164th was stymied in its efforts to break out of the bridgehead, and it soon became apparent that, instead of withdrawing, 3rd Panzer was preparing a defense that would guarantee another series of frontal assaults. The offensive collapsed on March 5.[38] After several weeks for replenishment, and to wait for the spring rasputitsa to abate, Western Front prepared for yet another offensive against Vitebsk. By mid-March the 164th had returned to 65th Corps, again with the 144th Division. Sokolovskii returned to his strategy of mid-January, planning to expand the salient southeast of Vitebsk farther to the south, this time employing three rifle corps, not including the 65th, on a 12km-wide front, supported by two tank brigades. The 164th remained holding its positions near Bondari on the north face of the salient. The assault began at dawn on March 21 and made gains of up to 4km by nightfall, but this proved to the extent of progress as German reserves arrived. Fighting continued until March 29 but by the 27th it was clear to both sides that the offensive had faltered. Furthermore, given losses of 20,630 men from March 21-30 there was nothing Sokolovskii could do to reinvigorate it. In the investigation that followed in April of the Front's operations over the winter it was reported that in several cases replacement troops had been committed to action prematurely:

In consequences of such failings and many more, on April 12 Sokolovskii was removed from Front command, joining Gordov, who had already been cashiered.[39] Operation BagrationAlso in April Western Front was split into 2nd and 3rd Belorussian Fronts. In the same month the 164th was moved to the latter, first joining the 5th Guards Rifle Corps in 39th Army.[40] The division was reassigned to the 84th Rifle Corps in the same Army in June, now in 1st Baltic Front, just before the start of the summer offensive. It would remain in this Corps for the duration of the war, although the Corps would be moved through several Fronts and Armies during this time.[41] It was under the command of Maj. Gen. Yu. M. Prokofev. Vitebsk–Orsha Offensive 84th Corps now contained the 164th, 158th and 262nd Rifle Divisions. The initial objective of this Army was drive westwards to help finally pinch off the Vitebsk salient; 84th Corps was tasked with pinning the German forces in the city while 5th Guards Corps formed the southern pincer. The Army went over to the offensive on the morning of June 23, targeting the 197th Infantry Division. A one-hour artillery preparation began at 0600 hours which did considerable damage to the defenders and their works. The 164th and 262nd were in the Corps' first echelon, and with armor support crashed through the German lines. By 1300 the two divisions had driven the 197th back to the Vitebsk–Orsha railway, with the 164th pushing shattered elements off to the northwest and continuing north along the railway, supported by the 957th Self-Propelled Gun Regiment (SU-76s).[42] and 610th Tank Destroyer Regiment. By evening the remnants of the 197th were within 15km of the center of Vitebsk and 8km west of the railroad.[43] During the next morning the Corps mounted a crushing attack on Vitebsk. At 1300 hours the 158th, which was holding a long sector east of the city, launched its holding attack. The 262nd pushed forward 6km from the south, while the 164th, late in the day, struck northward toward the corridor connecting LIII Army Corps with the remainder of its 3rd Panzer Army. It repulsed a German counterattack by two battalions of infantry, backed by 10 tanks and self-propelled guns while inflicting heavy losses. At about the same time the 5th Guards Corps linked up with 43rd Army, closing the pocket. During June 25 the 39th Army strengthened its junction with the 43rd in anticipation of relief/breakout attempts. Two regiments of 6th Luftwaffe Field Division and elements of 206th Infantry Division, again with armor support, launched up to 18 counterattacks against the 164th, 17th Guards Rifle Division, and part of the 91st Guards Rifle Division, but these were defeated with the help of air support.[44] At 0330 hours on June 26 the 158th Division crossed the Dvina River and entered Vitebsk. By 0600 the 262nd had joined the attack, cutting the main road close to the city. Another breakout attempt by some 1,000 German troops was defeated with heavy casualties by the 164th and the 17th Guards; the few that escaped were soon tracked down by other units of 39th and 43rd Armies. During the remainder of the day the city was cleared,[45] and the division was awarded an honorific:

By noon on July 27 some 7,000 prisoners had been taken and more were coming in.[47] Baltic OffensivesOn July 4 the STAVKA issued a new directive in which 1st Baltic Front was ordered to develop the offensive by launching its main attack in the direction of Švenčionys and Kaunas with the immediate task of capturing a line from Daugavpils to Pabradė by no later than July 10-12. It was then to continue the attack with its main forces on Kaunas as well as toward Panevėžys and Šiauliai. 39th Army was out of contact with organized German forces as it caught up with the remainder of the Front.[48] By July 19 it had crossed the eastern border of Lithuania near Švenčionys. Two weeks later, as the rate of advance slowed due to logistics and increasing resistance, the 164th was in the vicinity of Jonava.[49] Kaunas was liberated on August 1 and the 164th was rewarded for its role with the Order of the Red Banner on August 12.[50] Prior to this victory the 39th Army had been transferred to 3rd Belorussian Front.[51] Operation DoppelkopfWhen the German Operation Doppelkopf began on August 14 the division was positioned south of Raseiniai, and one of its rifle regiments, along with the 18th Guards Tank Brigade, were encircled at the village of Kalnuiai. Before long they were rescued by other elements of 84th Corps and units of 5th Guards Tank Army. Although German forces managed to take and hold Raseiniai, otherwise the 39th Army's counterattack drove them back to their start line after dark.[52] Later in August 84th Corps returned to 1st Baltic Front, now under 43rd Army.[53] Riga OffensiveBy mid-September 43rd Army had advanced northward to the vicinity of Bauska in Latvia.[54] As of the beginning of October 84th Corps had come under command of 4th Shock Army in the same Front.[55] This Army was straddling the border of Latvia and Lithuania in the area of Žagarė.[56] 4th Shock was not directly involved in the liberation of Riga on October 13 but for their roles in holding off German relief efforts the 531st and 620th Rifle Regiments were each awarded the Order of Alexander Nevsky on October 22.[57] Courland Pocket and Postwar84th Corps continued its roving commission during early 1945. German Army Group North was trapped in the Courland Peninsula of western Latvia, and the 84th was part of the forces committed to contain it. In January it was reassigned to 6th Guards Army, still in 1st Baltic Front, but within a month it was moved to 10th Guards Army in 2nd Baltic Front. When that Front was disbanded in March the Corps returned to 6th Guards Army, which was now part of the Kurland Group of Forces in Leningrad Front. The 164th and its Corps ended the war back in 4th Shock Army, still in the Kurland Group.[58] By this time its men and women shared the full title of 164th Rifle, Vitebsk, Order of the Red Banner Division. (Russian: 164-я стрелковая Витебская Краснознамённая дивизия). 84th Corps was soon moved to the South Ural Military District where the division was stationed at Chkalovsk. In May 1946 it was converted to the 16th Rifle Brigade.[59] ReferencesCitations

Bibliography

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||